The British defence of Malaya against the Japanese invasion in 1942 was in one word a ‘disaster’ and a good example of when and how not to fight a campaign. The History of the Baluch Regiment equates it to a tragedy and admits that the British Army was as hamstrung by their politicians (particularly PM Churchill) as the Wehrmacht was by Hitler. This is the story of how one of the best Baluch battalions fought in a futile campaign in Malaya and ended up suffering 3½ years of Japanese enslavement.

Apart from 14 British and Australian battalions, there were 23 Indian battalions and what happened to 2/10 Baluch in Malaya mirrors the fate of the rest. Like many other Indian battalions, 2/10 was a very old unit that had been raised in 1825 and had fought in the First World War. On the outbreak of the Second World War, it was under command the 8th Indian Division and after a year of training it sailed from Bombay in Sep 1940. In addition to 12 British officers, it had two Indian subalterns who had recently been commissioned – Abrar Hussain from Lucknow and Muhammad Ismail Khan from Peshawar. Both were from the First Indian Emergency Commission (IEC) Course and joined the battalion after a short training spell. Its soldiers comprised of a company of Pathans (Khattaks and Yusufzais), two companies of Punjabi Muslims and a fourth company of Dogras. Unfortunately, 150 of its best-trained men had been posted to freshly raised battalions and they were replaced by young soldiers from the training centre.

The battalion disembarked at ‘Fortress Singapore’ – which was a major British naval base but its defences were inadequate. The Japanese were well aware of this because they had not only broken the British Army cipher codes but also a German raider had captured a British steamer carrying top secret documents related to the weaknesses of the defences. On the other hand, the British had very little intelligence about the Japanese, and their impression of the opponents’ fighting capabilities was coloured by an element of the superiority of the white race over the Asians. The history of the 11th Indian Division (which was one of the two divisions defending Malaya), records that the prevalent view of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) was seen :as lying somewhere between the Italian and Afghan Armies.”

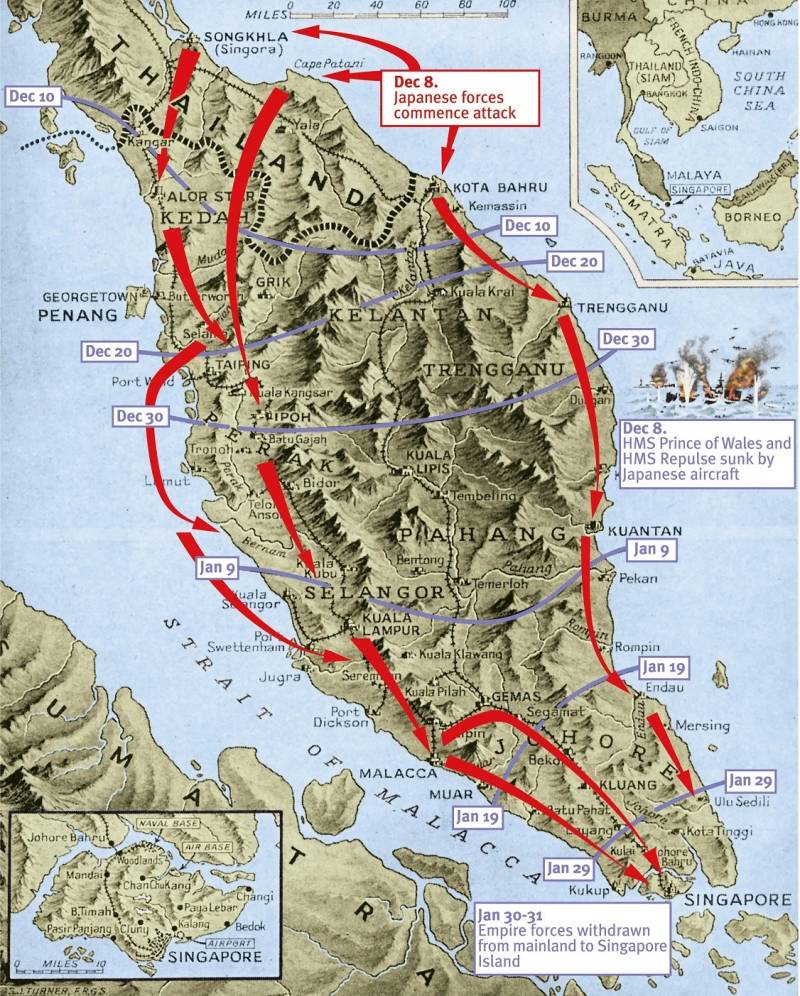

The battalion was issued 10 Bren gun Carriers which ostensibly improved its combat capability but in actual fact, it made the battalion road-bound and put them at a disadvantage against the Japanese tactics of using the jungle. Another 50 personnel were ‘milked,’ leaving not more than two men in a section with more than two years of service. The battalion was now moved up-country by train to Kelantan and placed under the 9th Indian Division. While the 11th Indian Division covered the approach along the western coast, the 9th covered the border with Thailand and the eastern coast. It had two Indian Brigades, and the primary task of the brigade under which 2/10 Baluch was serving, was to guard three airfields on the coast, and a secondary task was protecting the coast against a seaborne assault. The need to protect the airfields severely limited its freedom of action.

To add to the misperception of the IJA, the local commanders mistakenly considered that the thick jungle behind the coastal belt was impenetrable and that a Japanese landing would not be possible during the winter monsoons. Training for jungle warfare was in its infancy and in the year that 2/10 prepared for a Japanese landing most of the time was spent on constructing the defences along 30 km of the coast assigned to it. During this year two more Indian officers had been posted to the battalion – Capt PC Sehgul from 5/10 Baluch and Capt MAK Durrani from 2/2 Punjab. Both were commanding companies. Lt Abrar was the quartermaster and Lt Ismail was in the brigade HQ as the liaison officer.

The battalion had lost 40% of its manpower but fortunately, its CO discovered that there were sufficient Baluch reinforcements in the Rest Camp. They were not fully trained but they brought the battalion up to strength

The Japanese invasion of Malaya coincided with their attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. The brunt of the Japanese assault in the Kelantan sector fell on the battalions defending the coast north of 2/10. Within a day the Japanese air force had decimated the near-obsolete aircraft of the Commonwealth and within two days the defences had been turned. Contrary to popular belief, the Japanese were not overly experienced in jungle warfare but their units had an extensive operational experience that manifested itself in well-executed battle drills. They utilized the roads and tracks through the rubber plantations for a speedy advance on foot and bicycles, and opposition was outflanked through the jungle. The Japanese Army did not bring bicycles ashore but confiscated from civilians and retailers, thousands that they had exported to Malaya before the war.

Consequently, the brigade HQs at Kota Baru along with its battalions fell back to a new line of defence and 2/10 was forced to leave the beach defences it had so laboriously prepared over a year and heavy weapons and stores were abandoned. The morale was further badly affected by the news of the loss of two British battleships, the HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse which had foolishly attempted to interpose against the Japanese landings in northeast Malaya.

To break the momentum of the Japanese advance, the brigade HQ decided that 2/10 Baluch should launch an attack with two companies. After a quick reconnaissance, the companies advanced with difficulty through paddy fields. Devoid of artillery support but with covering fire provided by the Dogra company, the company on the left led by Capt Dyer reached the objective. However, the one on the right was held up 300 meters short. The companies were withdrawn with a loss of 18 killed, 22 wounded, and over 100 Japanese were killed.

The Japanese main effort was along the western coast held by the 11th Indian Division, which was forced to withdraw after it suffered some major defeats. The withdrawal by the 9th Division on the east was dictated by the disastrous fighting on the west coast and after the fall of Kuala Lumpur, on 10 Jan, 8th Brigade fell back another 200 km to Batu Anam. Here its battalions were echeloned in defensive positions astride the road with 2/10 holding well-wired defences where they were expected to fight for seven days. However, this was not to be. 1/13th FFR which was the foremost battalion was heavily attacked on 18 Jan and before the enemy could close up to the defences prepared by 2/10th Baluch, the brigade withdrew 10 km to its next position across the River Maur at Bulah Kasap. After the last of the stragglers had crossed, the bridge was blown as the Japanese appeared on the far bank. A healthy firefight ensued in which the Japanese for the first time used a form of firecrackers launched from a special weapon to rattle the defenders. When the firecrackers struck a rubber tree behind the positions of 2/10, they exploded with a large crack, giving the impression that the enemy had infiltrated behind.

Once again, it was planned to hold this position for some days but a very raw infantry brigade that had recently arrived in the sector of the 11th Indian Division was badly mauled in the Battle of Maur. However, an Australian division was now operating alongside the Indians and their encounter with the Japanese was one of the most savage of the campaign. The loss of Maur once again exposed the flank of 9th Division and 8th Brigade was forced to withdraw, this time by trucks 80 km to Kampong Chaard.

By now, the lateral distance between the two Indian divisions had contracted because the Malayan Peninsula narrows as it gets closer to Singapore. The line of withdrawal for two brigades of the 11th Division passed through the road junction at Yong Peng, which was protected by the 9th Division with 8th Brigade in front and 22nd Brigade in depth. After delaying the Japanese for a day, 8th Brigade successfully disengaged and pulled back at night however, when it was the turn of 22nd Brigade to withdraw, they found the bridge behind them demolished and a strong Japanese force behind them. Sadly, the brigade was decimated with few survivors. 8th Brigade kept withdrawing and on 30 Jan when they were 8 km short of Singapore, they received orders to withdraw into the island.

For the last two months, 2/10 had been constantly withdrawing, and like all the other units involved in delaying the Japanese advance, it desperately needed to reorganize. The battalion had lost 40% of its manpower but fortunately, its CO discovered that there were sufficient Baluch reinforcements in the Rest Camp. They were not fully trained but they brought the battalion up to strength. However, the battalion had to transfer a number of light machine guns to units that were short of this weapon. With the loss of 22 Brigade, 9th Indian Division had been disbanded and 8th Brigade was now under the command of 11th Indian Division.

By now, the battalion had six Indian officers. Capt Sehgal and Capt Durrani were both commanding companies. Amongst the lieutenants, the recent addition was Burhan Uddin, the son of the Mehtar of Chitral. He had been commissioned into 5/10 Baluch in 1936 and had volunteered for the Indian Air Force, where he earned his wing. However, in 1941 he opted to revert back to the army and joined 2/10 Baluch. Abrar was now the unit quartermaster and Ismail was back from the brigade HQ and appointed as the intelligence officer.

The much-vaunted fortress of Singapore had no prepared fortifications behind which the army could recover because the powers to be were of the opinion that building defences in rearward areas were bad for the morale of the troops and civilians. Consequently, the battle of Singapore did not last for more than seven days. After intense artillery bombardment, 13,000 Japanese crossed the Johar Strait on the west coast of the island and the defensive perimeter shrank. 2/10 came under a heavy attack and when the Japanese penetrated into their defences they called on the officers and men of C Company to surrender because a cease-fire had been announced. Both Capt Sehgal and Lt Burhanuddin succumbed to the Japanese and persuaded their men to do the same. The rest of 2/10 resisted bravely but the defensive perimeter around the city kept shrinking till on 15 February, the 85,000 British troops surrendered to a Japanese force half their number.

There is little on record of the 3½ years that the battalion spent in captivity. But the history of the Baluch regiment does mention that most of the VCOs and other ranks stood firm in spite of the horrors committed by the Japanese and the pressure to join the Indian National Army. Amongst the officers who displayed exemplary courage were Capt Durrani, Lt Ismail, and Abrar Hussain. After the war ended, both Durrani and Abrar Husain were appointed Members of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).

Following its release, the battalion sailed for Karachi where it faced a threat of being disbanded but Lt Gen Briggs one of its previous commanding officers intervened. The battalion was consequently reraised and merged with the 9/10th Baluch. In 1956 it was redesignated as 7th Baluch.

References

- Headrick, LCDR Alan C. Bicycle Blitzkrieg: The Malayan Campaign and the Fall of Singapore. Naval War College, 8 Feb 1994.

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/PTO/RisingSun/BicycleBlitz/#III

- Roy, Kaushik. Sepoys against the Rising Sun. The Indian Army in the Far East and South-East Asia, 1941-45. Brill, Boston.

- Thatcher WS. The Tenth Baluch Regiment in the Second World War, Baluch Center Press, Abbottabad, 1980.

- Khan, Muhammad Ismail. Oral history. Imperial War Museum, UK

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011491

- War Diary 2/10 Baluch, National Archives, UK