Be aware of friends, for they know the tunnel to your heart— Anonymous

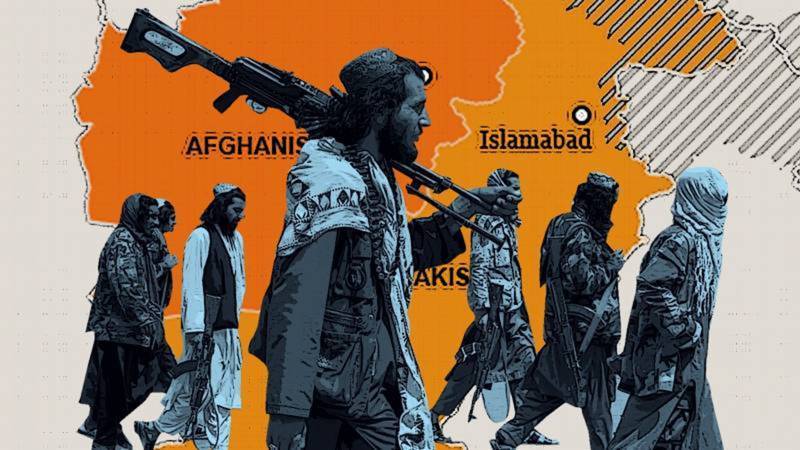

Upon the Taliban's return to power in Afghanistan, people from different walks of life celebrated the Taliban's rise. Above all, our leadership on both sides of the political divide sang hymns to the Afghan Taliban's glory with bombastic tweets. Many saner voices could foresee increasing turbulence in Pakistan in the aftermath of the Taliban takeover, but not our leaders. Populism more than anything else makes them blurt out statements without anticipating the consequences.

What caused this shift from high praises to strikes inside Afghanistan and friendship to a discordant relationship? The answer is over-expectations and a lack of understanding.

Pinning hopes that a friendly government in Kabul will settle all bilateral disputes and conduct foreign policy to Pakistan’s liking is too facile an understanding of the Taliban, based on miscalculation and denial of history. We need to understand the Taliban in Afghanistan's context.

The erroneous assumption in Pakistan that Afghanistan is predominantly a Pashtun country led us to put our weight behind the Taliban, largely a Pashtun outfit. By this, we alienated not only a large segment of anti-Taliban Pashtuns but also almost all non-Pashtun half of Afghanistan. The Taliban are not grateful to us either.

The Taliban views on Durand Line (an internationally recognised border) vary from an Islamist perspective that a dividing line between two Muslim countries has no justification to a purely nationalistic view expressed by the Taliban Deputy Foreign Minister, Stanikzai, recently, that “Afghanistan never has and will never recognise Durand Line.” Both views carry the same connotations. For most non-Pashtuns of Afghanistan, the Durand Line is an insignificant bilateral issue.

Afghans’ negative perception of Pakistan has been shaped by the turbulent situation in Afghanistan over more than 40 years. The international news about Pakistan’s interference in Afghanistan's internal affairs, the treatment of Afghan refugees in Pakistan, and the impression Afghans, especially the Taliban, gathered during their interactions with Pakistani authorities, reinforced this perception.

The best study of the Afghan Taliban is the study of Afghans. They are proud descendants of Mirwais Khan and Ahmad Shah Abdali, the founding fathers of modern Afghanistan. They may deny it, but subconsciously they are Afghans first and Muslims second.

The contempt the Taliban’s former ambassador in Islamabad, Mullah Zaeef, demonstrated for Pakistani authorities a feeling that finds expression in the Taliban's current behaviour towards Pakistani authorities: his views about ‘Pakistani establishment’s deep roots in Afghanistan, like cancer in the body, their sale of people for money, manipulation of talks, arrogance, dismissive attitude, and treatment of the Taliban as simple-minded people’ have been narrated by Zaeef in his book ‘My Life with the Taliban’.

The best study of the Afghan Taliban is the study of Afghans. They are proud descendants of Mirwais Khan and Ahmad Shah Abdali, the founding fathers of modern Afghanistan. They may deny it, but subconsciously they are Afghans first and Muslims second.

How much the Afghan Taliban values Pakistan is a moot question. Their close links with the Pakistani government and establishment and strong people-to-people contacts have made them better understand us than we do them. They have learned a lot from us; we haven’t from them.

The strong international pressure led by the US and Pakistan was ineffective in getting Osama bin Laden and others extradited from the Taliban 1.0. Will the current shaky Pakistani government be able to force the Afghan Taliban to repatriate leaders of the sisterly TTP to a regime they consider unIslamic?

Besides employing the TTP as a strategy to convey to Pakistan, not to underestimate them, the Afghan Taliban are also using it as a tactic to increase their support base among common Afghans, the majority of whom see Pakistan as their enemy number one. Regardless of the UN reports establishing TTP’s involvement from Afghanistan soil in the current wave of terrorism in Pakistan, many non-Taliban Afghans in defence of the Taliban maintain that Pakistan has gone one step up from denial to anger in the five stages of grieving. The other three stages, i.e., bargaining, depression, and acceptance, may take some time.

What options does Pakistan have on hand in case they withdraw support from the Taliban? None. We don’t have any friends left in Afghanistan. India and many others would be happy to step in. We can’t afford another hostile neighbour. The Afghan Taliban, comprising tough interlocutors, fully know our precarious situation.

All neighbours of Afghanistan are facing terrorism-related issues with the Taliban government. They have managed their relations well with the Taliban 2.0. We need to manage our relations well too.

Pakistan must work hard to repair its zero goodwill in Afghanistan. Supporting a spoiler party in Afghanistan will bring our investment in the Taliban to naught. Both countries must focus on the political aspect of the strategic depth by enhancing high-level interactions and not on the military dimension, which is bound to lead to further misgivings. Besides constant pressure on the Taliban not to allow its soil to be used against Pakistan, foremost, we need to respect Afghanistan’s sovereignty. The hot pursuit inside Afghanistan will further alienate Afghans, in addition to provoking international outcry on civilian harm and provide an excuse for India to strike inside Pakistan.

Internally, we should reinforce our security with zero tolerance for terrorism. Instead of addressing symptoms, the root cause of terrorism has to be treated. For a united stand against terrorism, we must take all political parties and stakeholders on board.

Populism should not dictate our policies. William Blake's saying in reverse order better reflects our dilemma about Afghanistan: Foresight is better, but hindsight is a wonderful thing. In the absence of foresight, we need to learn from our past to chart our future course.