It’s been a while since I was part of the target audience, but I don’t quite remember the young adult (YA) genre being as overwhelmingly prevalent as it seems to have become. Sure, we’ve just gotten past the Harry Potter hangover and we’re still trying to forget Twilight happened, but with the multimillion-dollar earning franchise of The Hunger Games trilogy, Hollywood has finally taken notice. Barely a few months go by before news of a new YA adaptation breaks, with the built-in loyal fanbase serving as catnip for marketing bigwigs. With scores of these adaptations still under development, it doesn’t seem this trend will end soon.

Amid all the commotion, it’s refreshing to see attention being lavished on a book completely devoid of supernatural, fantastical or dystopian elements. The Fault in Our Stars is a simple story of two star-crossed young lovers, Hazel and Gus, both inexorably precocious, and weighed down by a gravity that belies their age. They go easily from discussing the philosophy of advanced set theory to debating the spiritual significance of death. They’re frighteningly self-aware, cutting through much of the nonsense that their peers indulge in. Their courtship allows for a teenage experience that a cruel twist of fate has robbed them of: they’re both cancer patients. Nevertheless, no stone is left unturned in the brief time they have: they read books together, quote lyrics to each other, speak in elaborate metaphors, and stay up talking and texting way too late.

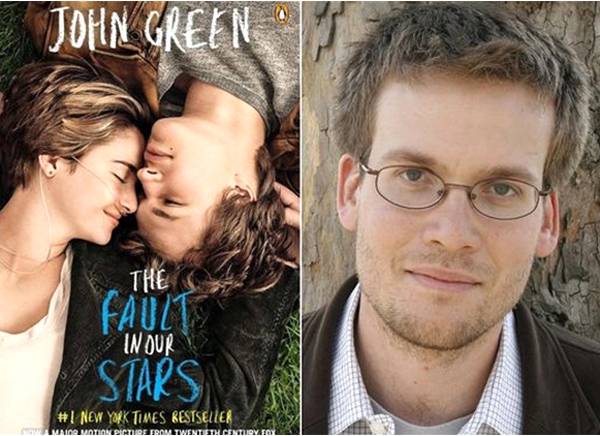

As someone who’s spent the better part of the last decade personally and professionally championing young adult literature, it warms my heart to see a book like The Fault in Our Stars earn critical and commercial accolades. It was name-checked in many a best-of-2013 list, it has over a million copies in print, and has now earned a blockbuster movie adaptation that beat out a Tom Cruise-starring action movie in its opening week. John Green, an author with four great books and a massive fan following to his credit already, deserves every moment of this success. That he has found it with his first full-length novel written from the female perspective is the cherry on the pie. But somewhere in the widespread adulation lies the disturbing tendency to gloss over the flaws in the narrative, and ignore the reality of the message therein.

I was aware of the magnitude of its popularity before the movie’s release—you’d have to be living under a rock not to. There were red carpet events that were reported more than I remember red carpet events being reported before. There were press junkets in which the movie’s very young, very sheltered leads (who incidentally also star in current dystopian YA craze, Divergent) said some very silly things about feminism. There were hordes of nerdfighters, a term used by the legions of John Green’s fans around the world, writing—nay, hyperventilating—about it all over the internet. But I had no inkling that I’d see it firsthand so far away from America, sitting here in the UAE.

[quote]My sister wore shoes paying homage to the book (with its trademark minimalist cloud graphic) and was immediately mobbed by strangers begging to know where she'd acquired them[/quote]

Tickets for opening day went on sale a week early, and there were lines. Young girls were breaking down into helpless sobs at the counters on hearing that it was rated 15+ and they wouldn’t be let in. My normally rational little sister (who gained entry pretending to be 2 years older) decided to wear shoes paying homage to the book (with its trademark minimalist cloud graphic) and was immediately mobbed by strangers begging to know where she’d acquired them.

They lined up at the concession stand buying popcorn and chocolate and packs of tissues, dressed in cyan, black and white merchandise as a tribute. They squealed and sighed every time Gus smiled. They clutched each other in wonder during the beautifully scored montages. They cried at the slightest hint of emotion. Even complete strangers held hands and hugged at the end of the movie, leaving me completely baffled. When caught in a sea of passionate, uninhibited teenage girls, one cannot help but feel terminally ancient.

Most often, though, I’d be hissed at for my derisive snorts. It is unfortunate that the movie adaptation sanitizes most of the deliberate imperfections in the book. At the heart of it, Hazel is an unreliable narrator whose perspective twists Gus into a disproportionately idealized concept. He’s impossibly cool with his abstract concepts of oblivion and metaphorical cigarettes and bizarre sense of adventure. He tells Hazel straight out that he finds her beautiful and he has vowed to win her over, her consent be damned. He lets his best friend Isaac break hard-earned trophies, he takes Isaac out to egg his ex-girlfriend’s car, he uses up his last big “Cancer Perk” to take Hazel to Amsterdam so she can meet her favorite author. In many ways, he is the gender-swapped ideal of the famed Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope, designed entirely to show Hazel out of her depressive black hole and prove that life, however fleeting, is worth living.

Although the narrative in the book eventually deconstructs this to some degree, by revealing his insecurities and shortcomings, the movie unfortunately gives his character no room to breathe. It features a pair of beautiful people masking their beautiful angst with their beautiful monologues knowing their time is limited by an ugly reality that will mostly happen off-screen. There is no telltale pallor in their skin, no significant hair loss to shock your senses. The grand trip to Amsterdam features clear skies and symbolically significant champagne. They share a passionate first kiss in Anne Frank’s house, which seems rather incongruent and horrific unlike the delicately constructed metaphor in the book.

The movie’s truly tragic undertones are confined to one or two scenes near the end where a protagonist is caught at his worst, in a stark, helplessly out of control situation as he vomits blood and cries desperately not to be seen this way. Or when Hazel’s parents (in remarkably understated and heartbreaking performances by Laura Dern and Sam Tramwell) continue to piece together their optimism day after day, all the while battling against an enemy they are completely helpless to save their child from.

Adolescence is a strange period of transition in which every single emotion is concentrated into a short period of time. The teenage years of Gus and Hazel and Isaac and their peers are consumed by an extremely condensed range of emotions, brought upon by a premature confrontation with their mortality. There’s rage, there’s joy, there’s grief, anxiety, fear and disappointment, and of course, above all, there’s love. All of this feels so much stronger when you can see the full stop to your life looming. It explains why so many teenagers are drawn to the story—it comes pre-integrated with a rational explanation for its displays of uninhibited emotion.

[quote]It makes you weigh the need to create something real and honest against the anxiety that it will be taken away from you[/quote]

What worries me is how the central theme is completely ignored. This isn’t a story of “true love”, per se, but one that asks audiences to come to terms with how inherently fleeting love and happiness are. There is no such thing as a soulmate or forever. It calls out to the teen belief that all is infinite, and provides the mathematical caveat that even infinity cannot escape qualifiers of magnitude. It reminds you of how senseless a villain cancer (and by extension, mortality) can be, and that feeling entitled to fairness is the ultimate naiveté. It makes you weigh the need to create something real and honest against the anxiety that it will be taken away from you, and shows you why the leap is worth it.

To reduce all this to a simple yearning for the characters written within is the real tragedy. After the screening I attended, girls wiped their eyes and exclaimed, “I wish I had a Gus in my life.” If the message had gotten across, they really wouldn’t.

Amid all the commotion, it’s refreshing to see attention being lavished on a book completely devoid of supernatural, fantastical or dystopian elements. The Fault in Our Stars is a simple story of two star-crossed young lovers, Hazel and Gus, both inexorably precocious, and weighed down by a gravity that belies their age. They go easily from discussing the philosophy of advanced set theory to debating the spiritual significance of death. They’re frighteningly self-aware, cutting through much of the nonsense that their peers indulge in. Their courtship allows for a teenage experience that a cruel twist of fate has robbed them of: they’re both cancer patients. Nevertheless, no stone is left unturned in the brief time they have: they read books together, quote lyrics to each other, speak in elaborate metaphors, and stay up talking and texting way too late.

As someone who’s spent the better part of the last decade personally and professionally championing young adult literature, it warms my heart to see a book like The Fault in Our Stars earn critical and commercial accolades. It was name-checked in many a best-of-2013 list, it has over a million copies in print, and has now earned a blockbuster movie adaptation that beat out a Tom Cruise-starring action movie in its opening week. John Green, an author with four great books and a massive fan following to his credit already, deserves every moment of this success. That he has found it with his first full-length novel written from the female perspective is the cherry on the pie. But somewhere in the widespread adulation lies the disturbing tendency to gloss over the flaws in the narrative, and ignore the reality of the message therein.

I was aware of the magnitude of its popularity before the movie’s release—you’d have to be living under a rock not to. There were red carpet events that were reported more than I remember red carpet events being reported before. There were press junkets in which the movie’s very young, very sheltered leads (who incidentally also star in current dystopian YA craze, Divergent) said some very silly things about feminism. There were hordes of nerdfighters, a term used by the legions of John Green’s fans around the world, writing—nay, hyperventilating—about it all over the internet. But I had no inkling that I’d see it firsthand so far away from America, sitting here in the UAE.

[quote]My sister wore shoes paying homage to the book (with its trademark minimalist cloud graphic) and was immediately mobbed by strangers begging to know where she'd acquired them[/quote]

Tickets for opening day went on sale a week early, and there were lines. Young girls were breaking down into helpless sobs at the counters on hearing that it was rated 15+ and they wouldn’t be let in. My normally rational little sister (who gained entry pretending to be 2 years older) decided to wear shoes paying homage to the book (with its trademark minimalist cloud graphic) and was immediately mobbed by strangers begging to know where she’d acquired them.

They lined up at the concession stand buying popcorn and chocolate and packs of tissues, dressed in cyan, black and white merchandise as a tribute. They squealed and sighed every time Gus smiled. They clutched each other in wonder during the beautifully scored montages. They cried at the slightest hint of emotion. Even complete strangers held hands and hugged at the end of the movie, leaving me completely baffled. When caught in a sea of passionate, uninhibited teenage girls, one cannot help but feel terminally ancient.

Most often, though, I’d be hissed at for my derisive snorts. It is unfortunate that the movie adaptation sanitizes most of the deliberate imperfections in the book. At the heart of it, Hazel is an unreliable narrator whose perspective twists Gus into a disproportionately idealized concept. He’s impossibly cool with his abstract concepts of oblivion and metaphorical cigarettes and bizarre sense of adventure. He tells Hazel straight out that he finds her beautiful and he has vowed to win her over, her consent be damned. He lets his best friend Isaac break hard-earned trophies, he takes Isaac out to egg his ex-girlfriend’s car, he uses up his last big “Cancer Perk” to take Hazel to Amsterdam so she can meet her favorite author. In many ways, he is the gender-swapped ideal of the famed Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope, designed entirely to show Hazel out of her depressive black hole and prove that life, however fleeting, is worth living.

Although the narrative in the book eventually deconstructs this to some degree, by revealing his insecurities and shortcomings, the movie unfortunately gives his character no room to breathe. It features a pair of beautiful people masking their beautiful angst with their beautiful monologues knowing their time is limited by an ugly reality that will mostly happen off-screen. There is no telltale pallor in their skin, no significant hair loss to shock your senses. The grand trip to Amsterdam features clear skies and symbolically significant champagne. They share a passionate first kiss in Anne Frank’s house, which seems rather incongruent and horrific unlike the delicately constructed metaphor in the book.

The movie’s truly tragic undertones are confined to one or two scenes near the end where a protagonist is caught at his worst, in a stark, helplessly out of control situation as he vomits blood and cries desperately not to be seen this way. Or when Hazel’s parents (in remarkably understated and heartbreaking performances by Laura Dern and Sam Tramwell) continue to piece together their optimism day after day, all the while battling against an enemy they are completely helpless to save their child from.

Adolescence is a strange period of transition in which every single emotion is concentrated into a short period of time. The teenage years of Gus and Hazel and Isaac and their peers are consumed by an extremely condensed range of emotions, brought upon by a premature confrontation with their mortality. There’s rage, there’s joy, there’s grief, anxiety, fear and disappointment, and of course, above all, there’s love. All of this feels so much stronger when you can see the full stop to your life looming. It explains why so many teenagers are drawn to the story—it comes pre-integrated with a rational explanation for its displays of uninhibited emotion.

[quote]It makes you weigh the need to create something real and honest against the anxiety that it will be taken away from you[/quote]

What worries me is how the central theme is completely ignored. This isn’t a story of “true love”, per se, but one that asks audiences to come to terms with how inherently fleeting love and happiness are. There is no such thing as a soulmate or forever. It calls out to the teen belief that all is infinite, and provides the mathematical caveat that even infinity cannot escape qualifiers of magnitude. It reminds you of how senseless a villain cancer (and by extension, mortality) can be, and that feeling entitled to fairness is the ultimate naiveté. It makes you weigh the need to create something real and honest against the anxiety that it will be taken away from you, and shows you why the leap is worth it.

To reduce all this to a simple yearning for the characters written within is the real tragedy. After the screening I attended, girls wiped their eyes and exclaimed, “I wish I had a Gus in my life.” If the message had gotten across, they really wouldn’t.