Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan held members of the National Assembly Standing Committee on Interior hostage for more than two hours. He lectured them on national security, refused to let them take tea until he finished, parried Karachi-specific questions, and collected applauds for no good reason.

The minister had agreed to grace the committee with his presence last Monday. He briefed the members on performance of his ministry. He talked and they listened. He began by announcing that he would not give a power-point presentation. Then he began to talk. The atmosphere resembled a remote public school where pupils are subjected to corporal punishment if they dare interrupt the teacher.

Surprisingly, the briefing was open to the media. Perhaps the minister wanted his tales of honesty and straightforwardness be documented and reported. Among those journalists was a veteran who wrote recently that the Obama administration has changed its views on Muslims and extremism after the interior minister’s recent visit to Washington, DC.

The interior minister told the committee he had canceled thousands of blue passports, withdrawn civil armed forces from VVIP duties, busted a network of corrupt officials, chased the militants to their graves, revamped the passport and identity card offices, and so on.

It was shocking when he revealed that some officials of police and his ministry were colluding with Pakistani prisoners who had been repatriated from foreign countries. He said at least four such prisoners were illegally released soon after they were handed over to the Pakistani authorities.

Without naming anyone, he also accused “some officials” of his ministry of trying to delay the automation and digitization of the ministry’s records. He assumed the inordinate delay would benefit the corrupt elements. After he finished the briefing, the committee chairman asked softly if they could have tea. The interior minster giggled and leaned back like a conqueror.

Then began a session of questions and answers. A woman Member of the National Assembly (MNA) complained that Islamabad traffic police gave her a ticket without good reason. The minster advised her to remove the plate saying ‘MNA’ from her car. A bearded member praised the minister for a “successful” operation at the MQM headquarters in Karachi. An angry MQM MNA explained his party’s position as soon as he got the opportunity to ask a question. He said his party had no connection with the suspects the Rangers had claimed to have arrested from Nine Zero. He refuted the allegations that the MQM was running a militant wing.

For political reasons, the interior minister refrained from discussing the raid during his presentation, but a security official says the military establishment will tighten the noose around the MQM leadership. “The arrest of Amir Khan is just tip of the iceberg,” he said.

Then, the Rangers filed a case against Altaf Hussain under the Anti-Terrorism Act. He was accused of threatening senior Rangers officials.

It is the same Altaf Hussain who has at least twice demanded the imposition of martial law in Sindh in the last three months. It was he who wanted the armed forces take control of Karachi and cleanse it. In a statement made after the symbolically important raid on his party’s headquarters, he admitted he was wrong. The MQM’s reaction was uncharacteristic for a party that paralyzes the entire city over small issues.

While the party has produced remarkable politicians like Mustafa Kamal and Haider Abbas Rizvi, it faces difficulty in disassociating itself from the people like Faisal Mota, Ubaid K-2 and Saulat Mirza.

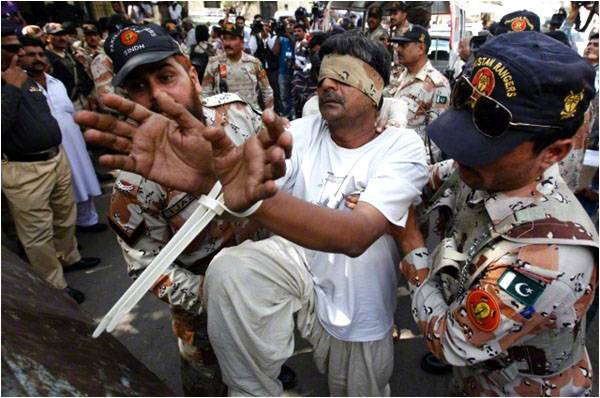

There is a context to this image.

In the mid-1980s Altaf Hussain is said to have urged his supporters to sell their television sets and buy weapons. The party converted a number of localities in Karachi into what were called ‘no-go areas’. Until the final days of second Nawaz Sharif government, its members were hounded and arrested throughout Pakistan.

A radical shift occurred after General Musharraf grabbed power in October 1999. The general wanted liberal secular politicians to legitimize his rule. The MQM was an obvious choice. Since its prominence in the national political landscape, the party has been finding it hard to get rid of its past.

Days ago, Altaf Hussain publicly admitted he was losing control of the party. Out of frustration, he has repeatedly reshuffled the Rabita Committee. In London, charges of money laundering are not his only problem. It has become an open secret that the military establishment has two cards against Altaf Hussain – the alleged murderers of Dr Imran Farooq. The British government has already demanded access to those two suspects. Pakistani authorities have apparently denied the request. This mounting pressure may be the reason why Altaf Hussain has made unwise public statements recently.

But he is also the unifying force in the MQM, and that is why he is important.

Shahzad Raza is an Islamabad-based journalist

Twitter: @shahzadrez

The minister had agreed to grace the committee with his presence last Monday. He briefed the members on performance of his ministry. He talked and they listened. He began by announcing that he would not give a power-point presentation. Then he began to talk. The atmosphere resembled a remote public school where pupils are subjected to corporal punishment if they dare interrupt the teacher.

Surprisingly, the briefing was open to the media. Perhaps the minister wanted his tales of honesty and straightforwardness be documented and reported. Among those journalists was a veteran who wrote recently that the Obama administration has changed its views on Muslims and extremism after the interior minister’s recent visit to Washington, DC.

The interior minister told the committee he had canceled thousands of blue passports, withdrawn civil armed forces from VVIP duties, busted a network of corrupt officials, chased the militants to their graves, revamped the passport and identity card offices, and so on.

It was shocking when he revealed that some officials of police and his ministry were colluding with Pakistani prisoners who had been repatriated from foreign countries. He said at least four such prisoners were illegally released soon after they were handed over to the Pakistani authorities.

Without naming anyone, he also accused “some officials” of his ministry of trying to delay the automation and digitization of the ministry’s records. He assumed the inordinate delay would benefit the corrupt elements. After he finished the briefing, the committee chairman asked softly if they could have tea. The interior minster giggled and leaned back like a conqueror.

Then began a session of questions and answers. A woman Member of the National Assembly (MNA) complained that Islamabad traffic police gave her a ticket without good reason. The minster advised her to remove the plate saying ‘MNA’ from her car. A bearded member praised the minister for a “successful” operation at the MQM headquarters in Karachi. An angry MQM MNA explained his party’s position as soon as he got the opportunity to ask a question. He said his party had no connection with the suspects the Rangers had claimed to have arrested from Nine Zero. He refuted the allegations that the MQM was running a militant wing.

For political reasons, the interior minister refrained from discussing the raid during his presentation, but a security official says the military establishment will tighten the noose around the MQM leadership. “The arrest of Amir Khan is just tip of the iceberg,” he said.

Then, the Rangers filed a case against Altaf Hussain under the Anti-Terrorism Act. He was accused of threatening senior Rangers officials.

It is the same Altaf Hussain who has at least twice demanded the imposition of martial law in Sindh in the last three months. It was he who wanted the armed forces take control of Karachi and cleanse it. In a statement made after the symbolically important raid on his party’s headquarters, he admitted he was wrong. The MQM’s reaction was uncharacteristic for a party that paralyzes the entire city over small issues.

While the party has produced remarkable politicians like Mustafa Kamal and Haider Abbas Rizvi, it faces difficulty in disassociating itself from the people like Faisal Mota, Ubaid K-2 and Saulat Mirza.

There is a context to this image.

In the mid-1980s Altaf Hussain is said to have urged his supporters to sell their television sets and buy weapons. The party converted a number of localities in Karachi into what were called ‘no-go areas’. Until the final days of second Nawaz Sharif government, its members were hounded and arrested throughout Pakistan.

A radical shift occurred after General Musharraf grabbed power in October 1999. The general wanted liberal secular politicians to legitimize his rule. The MQM was an obvious choice. Since its prominence in the national political landscape, the party has been finding it hard to get rid of its past.

Days ago, Altaf Hussain publicly admitted he was losing control of the party. Out of frustration, he has repeatedly reshuffled the Rabita Committee. In London, charges of money laundering are not his only problem. It has become an open secret that the military establishment has two cards against Altaf Hussain – the alleged murderers of Dr Imran Farooq. The British government has already demanded access to those two suspects. Pakistani authorities have apparently denied the request. This mounting pressure may be the reason why Altaf Hussain has made unwise public statements recently.

But he is also the unifying force in the MQM, and that is why he is important.

Shahzad Raza is an Islamabad-based journalist

Twitter: @shahzadrez