The origins of the Shahi Qila of Lahore are shrouded in the mist of times. Due to paucity of written records, the available sketchy information indicates that some sort of fort had been in existence since the inception of the city in the first few centuries AD. It would have been a mud structure at some location, and certainly not as massive as the later Mughal fort. The Rajput rulers of Lahore lost the city to Mahmud of Ghazni in the early 11th century. Mahmud, who had plundered and levelled the city during one of his seventeen raids, appointed Malik Ayaz, his favourite slave, as ruler of Lahore. This author has passed by the grave of Ayaz hundreds of times. It is located at the junction of Suha Bazaar (Goldsmith’s Lane) with the Shah Alam Bazaar.

It was Ayaz who rebuilt the city as the capital of the province. He also built a mud fort, called Katcha Kot, on a raised ground inside Lohari Gate. This fort along with the city was completely destroyed by the Mongols. Soon thereafter, Sultan Balban re-established the city and built the fort as the first line of defence against the marauding Mongols. This fort may have been at the site of the current Fort but the city was again ransacked and destroyed in 1398 by Amir Taimur. It was rebuilt by Sultan Mubarak Shah, the second ruler of the Syed Dynasty, who had disowned allegiance to the Timurid Sultans and strengthened the defences of Punjab against their raids. This was again a mud fort and its spread is uncertain but the city was again destroyed and partially burnt by Babur in 1524. Subsequently Humayun visited Lahore a few times, once after his defeat at the hands of Sher Shah Suri and then after his successful return from Persia. It can be assumed that Humayun, too, would have resided in the mud fort, whatever its condition may have been.

In view of this brief uncertain introductory history, it is evident that the story of the Fort as we see it today, commenced with Emperor Akbar.

The Fort is built on a knoll, rising from the city side and sloping steeply down towards the then bed of the Ravi. As one approaches the Fort either from the Shahi Mohalla road, as this author has done dozens of times, or from behind the Paniwala Talab on Fort Road, a route that this author traversed daily for one year in 1960 on way to his Municipal Corporation Primary School near Masti Gate, the southern stairs and wall of the Fort are visible on a high ground. This portion of the Fort has gardens, green areas and ramparts for protection. Nearly all residential and official buildings, as listed below, are on the northern side overlooking the then River. The southern side of the Fort, where the wall was demolished and stairs built by the British, is now only a few feet above the road but the northern side is still tens of feet high, with a picture wall forming its north western boundary. The north west corner of the Fort is so high above ground level that it contains a large well-furnished basement, as described below.

The books consulted for this article are the Akbarnama by Abul Fazl, Old Lahore by Col Goulding, Lahore Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities by SM Latif and some newspaper articles by officials of the Walled City Authority. Special thanks are reserved for the interactive map displayed at website maintained by Asian Historical Architecture. Although this author has visited the Fort many times, this website helped him in recalling all the structures in detail.

There are no structures in the Fort attributed to Aurangzeb. However, he built a majestic gate, named after him, for a direct access to his mosque. This gate is large enough to allow elephants to pass through

Abul Fazl noted in his Akbar-Nama vol-1 for year 1555, a year before Akbar became emperor, that Lahore was a great city of India. Unfortunately, he doesn’t mention the existence or location of a Fort, though it must have had one. Later, during the reign of Akbar, when the Subedar of Kabulistan, Prince Mirza Hakim, a troublesome stepbrother of Akbar, rose up in rebellion, the Emperor marched up to Kabul and, on his return, stayed in Lahore for a year and a half in 1581-82. Kabul again erupted in 1585 on the death of Mirza Hakim, forcing Akbar to march towards the city. However, his new Subedar, the trusted Man Singh, quickly brought calm to the city. Akbar received Hakim’s children at Rawalpindi and by the time he arrived at Attock after four months of travel in 65 marches over 805 kos or nearly 1,500 km (Akbarnama vol III), he didn’t feel the need to cross over. Instead, he returned to Lahore.

This time Akbar stayed in the Fort for fourteen years at a stretch from 1585 to 1599. Kabul, a province of the empire, Turan, which acknowledged Mughal supremacy, the Yousufzais, and some other Pashtun tribes who didn’t accept Mughal sovereignty, were frequently in political disturbance. Akbar found it convenient to continue his stay in Lahore, during which time, the Fort was the seat of a wide empire stretching from Kabul in the north to the upper Deccan in the south, and from Kandahar in the west to Bengal in the east. The emperor strengthened the Fort to reflect the glory of a rich empire and to make it impregnable.

Akbar removed the previous structures at the site and had the fort rebuilt with baked bricks, many of which continue to adorn its walls and buildings. Abul Fazl wrote that after his third and last visit to Kashmir in May-September 1597, Akbar lived in the new palace that was completed in his absence. That would be Akbar’s Quadrangle on the northeast corner of the fort close to the Akbari Gate. These are the oldest structures in the fort and include Akbari Mahal, Daulat Khana Khaas-o-Aam, Akbari Hammam, the massive Akbari Gate, the Jharoka and the spacious gardens. Akbari Mahal, the area designated for emperor’s living is now also called Haveli Kharak Singh because during the Sikh rule, another story was added to this building as the living quarter of Ranjit Singh’s eldest son who followed his father as the Sikh Maharaja but was deposed within four months.

Akbar’s double storied Jharoka (balcony) was the place where he would sit to conduct state business, and for darshan (viewing by public/officials). During the reign of Akbar and Jahangir, a triple canopy of velvet was erected in front of the Jharoka to provide the courtiers protection from the sun. Behind the Jharoka, Shahjahan later built the forty-pillared, beautifully decorated Dewan-e-Aam with seven jharokas, the central one being the largest for the Emperor. This building was destroyed during the Sikh civil war but rebuilt by the British.

During the initial period of his long stay in the Fort, Akbar was blessed with a grandson; a son born to Prince Salim (later Emperor Jahangir) and his consort Manbhawati Bai of the State of Amber. Describing the occasion, Abul Fazl (ibid, vol 3, pp 799) wrote of the birth that it was one of the great gifts of God, and the most excellent fruit of age and that the universe had new expansion and mankind had new strength. Notwithstanding Akbar’s joy and Abul Fazl’s hyperbole prose, the unfortunate Prince Khusro would rebel against his father. Having suffered defeat in 1606 on the northern banks of the Ravi near Lahore, he would be blinded in the Fort of his birth. He was still in his teens at 18 years of age. The blind prince would go on to live under detention or in prison for another sixteen years before his death in 1622 in Burhanpur; probably killed on the orders of his younger brother, the future Emperor Shahjahan who had taken over custody of the elder brother.

A number of historical events took place while Akbar was stationed in Lahore. Many expeditions were planned in the Fort against Gujrat, Deccan, Swat and Kabul. Some of the more important will be described below.

Soon after his arrival, Akbar despatched a large army to Swat against the ever restive Yousufzai tribesmen. The fifty thousand strong army under Birbil, one of his Nauratans, was on its way to Buner from Barikot, when it was ambushed by the Yousufzais between Karakar and Malandari passes. The Mughals suffered their worst defeat till then. According to historian Khafi, the whole army was lost; killed or captured. Birbil himself and, according to Abul Fazl (ibid), a number of commanders known to the Emperor, lost their lives. Akbar was grieved and did not eat for two days. He later sent another army that killed and captured a great number of tribesmen, with some of the prisoners sold into slavery in Turan and Persia.

Another notable military expedition planned at the Fort was in the opposite direction; to the Deccan, against the redoubtable Chand Bibi. Mughal forces laid siege to her Ahmednagar fort but could not breech its defences. Abul Fazl (ibid) has recorded a number of reasons for this failure. The Mughals then negotiated peace earning a face saving territorial concession. However, Mughal army under Prince Danial later defeated Chand Bibi, who was killed by her own troops for suspected treachery.

A notable military victory for Akbar was his conquest of Kashmir; planned and executed from the Fort. Akbar subsequently made three visits to Srinagar during his stay at Lahore. He was enamoured by the beauty of these hills and lakes, as was Jahangir, who accompanied his father on each of his visits. Akbar would leave Lahore for Agra after his third visit in 1598.

Prince Khurrram, later Emperor Shahjahan, was also born in the Fort during Akbar’s stay. Among the important deaths at Lahore were of Mian Tansen, the musician of the court, and Mai Danga, Akbar’s wet nurse.

After Akbar, Jahangir built his quadrangle immediate west of Akbar’s original buildings. Its construction began during Akbar’s time but was completed during Jahangir’s reign. It includes a garden that is not in the classic Persian chahar-bagh (four gardens) style but consists of three concentric rectangles with a fountain in the middle. The other buildings are the Mashriquie (eastern) and Magharbi (western) Burj (tower). During his own reign, Jahangir built his Khawab-gah (sleeping quarters) in this location. In conformity with Akbar’s syncretic approach, the brackets supporting the roof over the columns of this buildings are carved red sandstone animals such as elephants, lions and peacocks.

Jahangir also ordered that the north western portion of the Fort wall should be tiled with seven thousand square meters of mosaics depicting hunting and royal recreation. The wall between the northwest corner and the Shah Burj gate has slightly inset and bordered scenes of animals, angels, trees and vegetation. The angels are an indication of Jahangir’s interest in Christianity. Behind this area of the wall is the Pari Mahal, basement Palace for the royal ladies. Windows and jharokas of this palace are framed by these paintings to give it a colourful festive look.

True to his reputation as a master builder, Shahjahan added many buildings to the fort during his reign, some of which became very renowned. Shahjahan’s quadrangle was built under the supervision of Wazir Khan, then governor of Lahore. The governor must have been a great architect as testified by his Wazir Khan Khan mosque that he built in the Kashmiri Bazaar near the Akbari Gate. The quadrangle overlooks the northern Fort wall between Shahjahan’s Khilwat khana on the west and Jahangir’s quadrangle on the east. It contains Shahjahan’s sleeping quarters and Diwan-e-Khas (chamber of special audience), which was converted to a chapel during the initial British era but later restored to its original state. The Diwan-e-Khas has, on each of its three sides, five arches of carved marble that stand on artfully made marble columns. Its northern side has intricately made marble jali (perforated screens, mesh) for a scenic view of the river. The northern and southern portions of the quadrangle are separated by a char-bagh with a scalloped fountain in its centre.

The Khilwat Khana (House of Solitude) was the residence of Shahjahan and his harem. It is an enclosed and self-contained enclosure overlooking the northern wall and surrounded by Kala Burj on the left and the Red Burj on the right. The sleeping quarters are on the northern side with a private mosque on the left lower corner. There is a Paen Bagh (sunken garden) in the centre comprising two chahar-baghs (four garden) separated by a central pathway. The northern section contains the private chambers of the Emperor and the harem. On the southern side is the hammam (washing area) and, outside, the rooms for servants and the guards. In the centre on the northern side is a curved roof sitting area with an excellent view of the River and beyond. This sitting room is the precursor of the much more decorated Naulakha Pavilion.

The Shah Burj Quadrangle lies in the northwest corner of the Fort. It contains some of the most remarkable structures of the Fort complex located around a central courtyard with a large shallow cistern in the middle. The cistern is provided water through the southern chambers over a slanted patterned chute in the wall that drains into a basin on the floor and connects to a sandstone channel flowing to the cistern. The building was the residence of the empress when she visited Lahore. Shahjahan built these buildings as his work area too. It includes the Shah Burj Gate, the Sheesh Mahal and the Naulakha pavilion. An eight-door building called Athdara was added during the Sikh rule as the working area of Ranjit Singh. The Shah Burj corner is next to the elephant station which is connected to the road outside through elephant stairs and the elephant gate. The stairs are shallow and large for elephants to negotiate easily.

Shah Burj includes chambers along the southern wall, Naulakha Pavillion along the western wall enclosed by a dalan (gallery) on each of its two sides, the Masumman Burj (jasmine tower) along the northern wall, two smaller octagonal chambers on each side of the Masumman Burj, a staircase to the upper floor and a dalan on the eastern side. All buildings along the outer walls have attractive marble jalis for view beyond. The Masumman Burj contains the Sheesh Mahal, located on the north side of the courtyard and overlooking the then active river bed. A watchtower in the shape of a burj was added on top this structure during the Sikh rule. The Shah Burj Gate, which had been damaged and was inaccessible, has now been restored by the Walled City Authority.

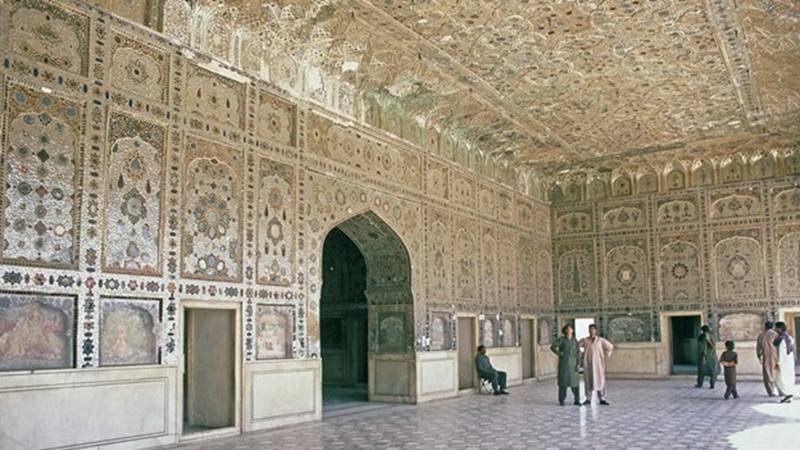

Sheesh Mahal (the Hall of Mirrors) is the most beautiful and the best-known structure in the Fort; and certainly, next to the Taj Mahal, the most exquisite building of Shahjahan. Its construction began during his father’s reign. Its façade consists of five cusped marble arches that open up to a courtyard. The roof of the inner hall rises up to two stories. Its walls are decorated with parchinkari, a technique to lay polished coloured stones to create images. Literally thousands of coloured glass pieces are laid in intricate and elegant manner to create enchanting patterns and reflection of light.

One of the most intriguing structures in the Fort is the Summer Palace or the Pari Mahal (Fairy’s Palace) built by Shah Jahan under the Sheesh Mahal. This basement building, with its windows opening on the then River Ravi, provided a cool and airy place as an escape from the summer heat. The Mahal had a double floor with provision for water being lifted from the river and channelled between the layers, as well as through 42 waterfalls and cascades. The coolness, the fresh air and the enchanting view of the river and the vegetation beyond provided an ideal relaxing place to the royal ladies and members of the household. The British used the place as a store for Civil Defence during WWII; a use that continued till 1973. The dampness and the misuse caused deterioration of the building but is being restored by the Walled City Authority Lahore with the assistance of Agha Khan Trust for Culture.

Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) built with white marble by Shah Jahan is a graceful and tasteful structure. It stands before Shah Jahan’s quadrangle. It’s a small mosque, with three domes supported by five arches and six elegantly carved columns; all made of fine white Makrana marble, quarried, according to historian Ravinder Nath, from Rajasthan. The whole mosque is enclosed by high walls. Outside the mosque is the Maktab Khana (the library).

There are no structures in the Fort attributed to Aurangzeb. However, he built a majestic gate, named after him, for a direct access to his mosque. This gate is large enough to allow elephants to pass through, and is set within two round ramparts decorated atop with a small dome each. The gate itself is constructed a few feet higher than the base of the wall with a broad and gently rising pathway, probably to keep flood waters out. Alamgiri Gate is witness to the fickleness of power. The Mughal emblem used to fly over it till being replaced by the Durrani flag. Sikhs hoisted their own triangular Nishan Sahib in the later part of the 18th century. Then in 1849, the Sikh flag, having fluttered for half a century, was replaced by the British Union Jack. The British lorded over this land for a century before being forced to leave. The flag representing a united East and West Pakistan was hoisted here for a quarter of a century. The national flag of rump Pakistan now flies uncertainly high over this gate.

When Ranjit Singh captured the Fort in 1799 from Bhangi Misl, it became centre of power for the Punjab Kingdom. He repurposed several places of the Lahore Fort for his own use. For example, Moti Masjid was converted into a gurdwara and Fort’s Naag (snake) temple was added. In Jahangir’s quadrangle, Ranjit added two Sehdaris (three-door pavilions), one on each side of the Khawabgah. Only one of them survives which was under the use of Faqir Azizuddin, Ranjit’s trusted foreign minister. Mai Jindan Haveli is perhaps of Mughal era origin but under her use. Jindan was the mother of Duleep Singh, the last Sikh Maharaja. It is also the place where Maharani Chand Kaur, a daughter in law of Ranjit Singh, may have been murdered. The building is now devoted to Sikh heritage. The first floor of this two-story building houses the collection of Princess Bamba, the daughter of Duleep Singh, containing many paintings and artifacts.

Ranjit Singh built an elevated pavilion with eight openings, hence its name Athdara, near the Shah Burj quadrangle. Made of red sandstone and marble, probably removed from other Mughal era structures, its walls and ceilings are decorated with motifs, frescoes and images. It was used as the royal court by the Sikh Darbar. Chand Kaur commissioned the Naag temple near the Shish Mahal. Its walls were decorated with frescoes. The temple remains closed to the public due to security reasons.

The Sikh civil war, after the death of Ranjit Singh, resulted in severe damage to the Fort. The famous Diwan-i-Aam was destroyed when Ranjit Singh's son Sher Singh bombarded the hall in his fight against Chand Kaur. Soon thereafter, Raja Hira Singh bombarded the Fort at the besieged Sindhanwala Sardars, resulting in more damage.

Sheesh Mahal is also the site of a great heist. According to William Dalrymple and Anita Anand in their book titled ‘Koh-i-Noor’, it was here on 29 march 1849 that a ten-year-old Duleep Singh, the youngest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, was forced to sign away his kingdom and treasury to the British. He was also forced to present Koh-i-Noor, the most famous jewel in the world, to Queen Victoria. Since 1937, the diamond adorns the crown of the Queen Mother, consort of King George VI, and is currently on display in the Jewel House at the Tower of London.

Moti Mosque was converted to Moti Mandir by Ranjit Singh, but it was used as the treasury throughout the Sikh era. The British seized the treasury along with the jewels and continued to use it for the same purpose. Dr John Login was appointed as the first British governor of the Fort. He catalogued the treasury items found in the Moti Masjid with utmost care and honesty. It was here that Login and his assistants found the Koh-i-Noor wrapped in velvet cloth. The treasures seized were worth about a trillion pounds sterling in today’s currency; not including the Koh-i-Noor, which was considered priceless.

According to a Guardian story, an India Office report lists “a pearl necklace consisting of 224 large pearls” as part of loot from Punjab. In her 1987 study of royal jewellery, Leslie Field described “one of the Queen Mother’s most impressive pearl necklaces … made from 222 pearls with a clasp of two magnificent rubies surrounded by diamonds that had originally belonged to the ruler of the Punjab” – almost certainly a reference to the same necklace. In 2012, Queen Elizabeth II attended a gala festival at the Royal Opera House in London to celebrate her diamond jubilee wearing a multi-string pearl necklace with a ruby clasp. The late queen had no embarrassment in wearing jewels that its officials stole from the Fort. Another piece of jewellery known to have been taken from the Fort to Royal jewels collection is a green emerald girdle.

The British opened a school in the Fort in August 1858 for European and Anglo-Indian children (Goulding, ibid) with 44 students; 24 boys and 20 girls. The first photographic studio was also established in the Fort by a pharmacist of the British garrison, who, as reported, did quite a good business. As the British took their sports as seriously as their warfare, the military and civil occupants of the Fort played their first racing, polo and cricket games under the northern walls of the Fort in what later was called the Minto Park.

(Photograph: Royal Collection Trust)

The Fort was heavily damaged during the Sikh civil wars between the death of Ranjit Singh and its conquest by the British forces. The later cleared away the debris, built some new barracks for their troops and restored some of the damaged buildings. Ravages of time, weather and neglect too took their toll on the once elegant structures. The Lahore Walled Authority has done a remarkable work in restoring some of these structures to their old glory with the financial and technical support of Agha Khan Trust for Culture. Restoration of Shah Burj Gate began in 2019 and was completed in 2020. The last time this author visited the place in 2020, the Sheesh Mahal and the Shah Burj gave a decent look. Other restoration works were undertaken in Sheesh Mahal, Naulakha Pavilion and Pari Mahal.

The Lahore Fort is a major heritage site of Pakistan, and a very rewarding place as a tourist destination. It is hoped that the site is preserved for the future generations.