Afghanistan suffers from chronic instability since the 1980s if not before. Wars, foreign occupation, civil armed conflict, economic dependency, human rights issues, political and social authoritarian and lingering refugee’s crisis have plagued this country for decades. The US-led Western forces failed to stabilise Afghanistan and they ultimately decided to pullout due to various considerations. Consequently, the power vacuum was filled by the Taliban in August 2021 largely due to their sustained resistance awaits foreign occupation. Despite the Taliban in power, Afghanistan’s problem persist. More than half of the population is facing starvation due to poor economic base and financial dependence on Western powers. Socially, there is a ban on women education. Politically, no country has formally recognised the Taliban regime so far. These pertinent questions are addressed in The Uncertain Future of Afghanistan: Terrorism, Reconstruction, and Great-Power Rivalry (Springer, 2024). This edited book analyses the domestic politics and external relations of the Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. It touches upon some of the key issues affecting the Taliban regime such as peace negotiations, terrorism threats, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and economic cooperation, policies and projections of the US-led Western powers, strategic and commercial interactions of Russia with the regime as well as responses of the neighbouring countries toward the Taliban 2.0.

The book is professionally edited by Nian Peng and Khalid Rahman. Nian Peng is an Associate Professor and Research Fellow at the Department of Foreign Languages and Research Centre for Indian Ocean Island Countries, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China. He is also the Director of the Hong Kong Research Centre for Asian Studies (RCAS), Hong Kong. His recent publications include Populism, Nationalism and South China Sea Dispute: Chinese and Southeast Asian Perspectives (Springer, 2022) and The Reality and Myth of BRI’s Debt Trap: Evidence from Asia and Africa (Springer, 2024). His refereed articles have been notably published in Ocean Development and International Law, Pacific Focus, Asian Affairs, etc. Khalid Rahman is chairperson of the Islamabad-based think-tank, the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS). He has more than 35 years of experience in research, training, and management. Rahman is also a non-resident fellow of the Research Centre for SAARC States (RCSS), Hainan Normal University, Haikou, and the Research Centre for Social Development of Islamic Countries, Hebei University. He is also editor-in-chief of Policy Perspectives.

Thematically, the book is divided into ten chapters. The opening chapter serves as an essential introduction, laying the groundwork for understanding the labyrinth of challenges confronting Afghanistan. It outlines the book’s core objectives, presenting a tapestry of key questions that are addressed in the subsequent chapters. These questions delve into the historical context that shaped the rise of the Taliban regime in August 2021, the ideological fault lines that impede peacebuilding efforts, and the multifaceted challenges that hinder Afghanistan’s path towards stability and progress. Chapter 2 by Muhammad Azam, based at Sargodha University, delves into the intricate history of Afghan peace negotiations, a saga fraught with missed opportunities and persistent roadblocks. It meticulously dissects the factors that continually thwarted progress on the path to peace. Ideological divides between the Taliban and Western democracies emerge as a prominent obstacle. The Taliban’s interpretation of Islamic law stands in stark contrast to the ideals of a Western-style democracy, creating an ideological chasm that seems difficult to bridge, argued the author. Furthermore, the presence of US-led foreign forces in Afghanistan is identified as another impediment. Their involvement was viewed with suspicion by Afghans particularly the Taliban, who perceived it as an infringement on their sovereignty. This perception fuelled anti-government sentiment and complicated the peace talks with the US. The chapter further underscores the absence of trust as a critical hurdle. Years of conflict have fostered a deep sense of distrust among key stakeholders, making it challenging to establish a foundation for genuine dialogue and reconciliation. In addition, the chapter sheds light on the complex web of actors and spoilers who have a vested interest in the continuation of the conflict. These actors, both domestic and international, often have agendas that diverge from achieving lasting peace, further complicating peace negotiations.

Mairaj ul Hamid Nasri delves into a critical retrospective of the US intervention in Afghanistan, in a chapter that offers a candid examination of the shortcomings of US policy

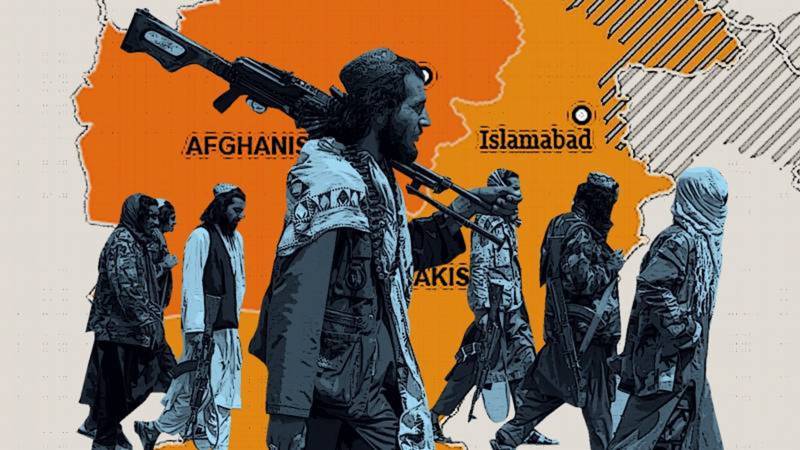

In Chapter 3, Mansoor Ahmad Khan and Muhammad Tahir Khan shift the focus to the Taliban regime itself, examining the formidable challenges they face in governing war-ridden and poverty-stricken Afghanistan. The authors have identified security concerns remain are still paramount. The presence of numerous terrorist groups, i.e. Al-Qaeda, within Afghanistan’s borders poses a significant threat to regional security. Indeed, Pakistan has repeatedly communicated the presence of Kabul-backed TTP inside Pakistani territory. The TTP has killed scores of Pakistani civilian and security personnel in recent years, too. The international community is understandably apprehensive about the Taliban’s ability or better willingness, to dismantle these groups. Chapter 3 also explored the issue of international recognition of the Taliban regime. The regime craves legitimacy and a return to the international fold. However, securing recognition from the international community hinges on their ability to demonstrate a commitment to human rights, particularly women’s rights, and to establish a more inclusive form of government, argued the authors. In addition, the authors also analysed the economic challenges confronting the war-torn nation-state. Rebuilding Afghanistan’s infrastructure and reviving its economy require substantial resources and international investment. The Taliban needs to navigate a delicate path, attracting foreign investment while simultaneously addressing concerns about corruption and mismanagement.

Chapter 4 by Yu Hong Fu examines the critical issue of security under the Taliban rule, a topic that evokes anxieties within the international community. The chapter explores the international community’s concerns about the potential for a spillover of instability and terrorism beyond Afghanistan’s borders. The author’s contends that a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan could become a breeding ground for extremist groups, posing a global security threat. However, the chapter also presents a more nuanced perspective. It suggests that the immediate impact of the Taliban takeover on extremist activities outside Afghanistan may be limited. While online propaganda and radicalisation efforts pose a concern, there is limited evidence of a significant increase in cross-border terrorist attacks in other countries especially the Western world. The chapter goes on to analyse the rise in terrorism within Pakistan since the Taliban takeover. This trend highlights the complex and interconnected security challenges plaguing the region, argued the author. It underscores the need for regional cooperation in addressing these challenges.

Mairaj ul Hamid Nasri delves into a critical retrospective of US intervention in Afghanistan following the 9/11 attacks in Chapter 5. The chapter offers a candid examination of the shortcomings of US policy, highlighting the immense financial costs and human losses incurred during the long and ultimately unsuccessful war. The chapter dissects the multifaceted objectives of US intervention, drawing a distinction between the stated goal of fostering democracy in Afghanistan and the more covert objective of securing regional influence and controlling access to resources. The chapter goes on to criticise the US policy framework, arguing that it failed to take into account the historical context and cultural nuances of Afghanistan. Imposing a Western model of democracy onto a society with vastly different traditions and political structures proved to be a recipe for failure. The author conclude the chapter with a call for introspection on the part of the US. It emphasises the importance of learning from the mistakes of the past intervention and urges reflection on the role of regional actors in shaping Afghanistan’s future. The chapter suggests that a more nuanced approach, informed by a deeper understanding of Afghan history and culture, is necessary for any future engagement with the country.

Chapter 6 by Xin Yi Qu and Nian Peng carries the discussion forwards with empirical focus on the Belt and Road Initiative in Afghanistan’s socioeconomic development. The BRI is a vast infrastructure development project encompassing numerous countries across Asia, Africa, and Europe. The chapter explores the idea that BRI projects could offer a glimmer of hope for Afghanistan, fostering economic growth and regional connectivity. It envisions a form of triangular cooperation between China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, where infrastructure projects could create a ‘win-win’ situation for all the involved stakeholders. For example, China would gain access to new markets and resources; Pakistan would benefit from improved trade routes, and Afghanistan could experience much-needed economic revitalisation via the BRI. Nonetheless, the authors also acknowledged the challenges that lie ahead. For distance, security concerns remain a major obstacle, with the ongoing presence of militant groups posing a threat to the stability of BRI projects. In addition, competition from other regional powers, particularly India, could complicate BRI’s implementation in Afghanistan.

Najimdeen Bakare, in Chapter 7, delves into the history of Russia’s involvement in Afghanistan, analysing the shift in their strategic posture following the Soviet withdrawal in 1989. The chapter also sheds light on Russia’s renewed strategic interest in Afghanistan after the US invasion in 2001. The NUST-based author argued that Russia views a stable Afghanistan as essential for its own security, particularly in light of the potential for regional instability to spill over into Central Asia, a region with significant Russian interests. Informally recognising the Taliban as a major player in Afghanistan, Russia advocates for engagement with the regime, believing that isolation will only exacerbate the situation. The chapter concludes by emphasising the potential for cooperation between Russia and other regional actors, including China and India, in pursuing the shared goal of a stable Afghanistan for market connectivity and regional economic integration.

Muneeb Yousuf and Nazir Ahmad Mir, New Delhi-based scholars, have analysed the multifaceted relationship between India and Afghanistan and India’s concerns about the Taliban’s return to power in 2021 in Chapter 8. The chapter identified India’s primary security concern as the potential for increased support for separatists in Kashmir from a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. India has provided significant economic and development assistance to Afghanistan during the Karzai and Ghani period. The authors also identified the challenges India faces in the current context such as the growing influence of China in the region. The authors concluded the chapter by outlining a potential strategic approach for India, which emphasises the need for the latter to maintain a multifaceted relationship with Afghanistan, balancing its security concerns with continued engagement on developmental issues. In addition, India’s soft power initiatives, focused on education and cultural exchange, could prove valuable in fostering long-term positive relations with the Afghan people, argued the authors.

Khalid Rahman, in Chapter 9, analysed the intricate and often troubled relationship between Pakistan and Afghanistan. The author emphasised the historical and cultural ties that bind the two countries, highlighted the porous border region and underscored the shared Pashtun heritage of many Afghans and Pakistanis. The author also acknowledged the complexities of the bilateral relationship. Moreover, Rahman has identified challenges that Pakistan is facing in its partnership with the US post-9/11. In addition, the author argues that a well-defined foreign policy is crucial for Pakistan, which ought to prioritise national interests while also fostering cooperation with Afghanistan on issues of mutual concern such as counterterrorism and managing the refugee crisis.

In the final chapter, Hideaki Shinoda, a Tokyo-based scholar, reflects on Japan’s involvement in Afghanistan post-9/11. Despite being a top financial donor, Japan’s efforts in Afghanistan faced challenges due to its traditional non-military stance and volatile security situation. Shinoda argues that Japan’s experience in Afghanistan impacts its future peace-building efforts. However, he suggests that Japan’s role will be more modest, focusing on harmonising with international efforts rather than leading large projects.

Thus, the book reflects diverse perspectives of scholars from China, Japan, and South Asia, providing a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted issues in Afghanistan. Each chapter offers unique insights, contributing to the overall analysis of Afghanistan’s complex political, economic, and security landscape. It is a recommended read for students, scholars, NGOs and policymakers working on Afghanistan, South Asian politics and security, the BRI as well as terrorism and great powers’ rivalries.