Few people think of Islamic religious seminaries or madrassahs (madaris) as symbols of anticolonial resistance. However, when the term madrassah is invoked, the reaction from the recipient depends on which end of the political spectrum they belong to. Those on the right-wing hail it as a pertinent alternative to the economically burdensome private education system, as well as the quality-deficient public education system. Those on the left, informed by the recent connection with terrorist movements and cases of exploitation that originate from madrassahs, call for abolishing such institutions altogether.

But neither of these groups acknowledges the historical origins of madrassahs in South Asia. Consequently, their reform and regulatory proposals tend to be reductive since they overlook the historical roots of madrassahs which provides a richer perspective on their role and potential in modern society. The sustenance of madrassahs in present-day Pakistan is a continuance of a search for the Muslim identity that is threatened by top-down, elitist politics.

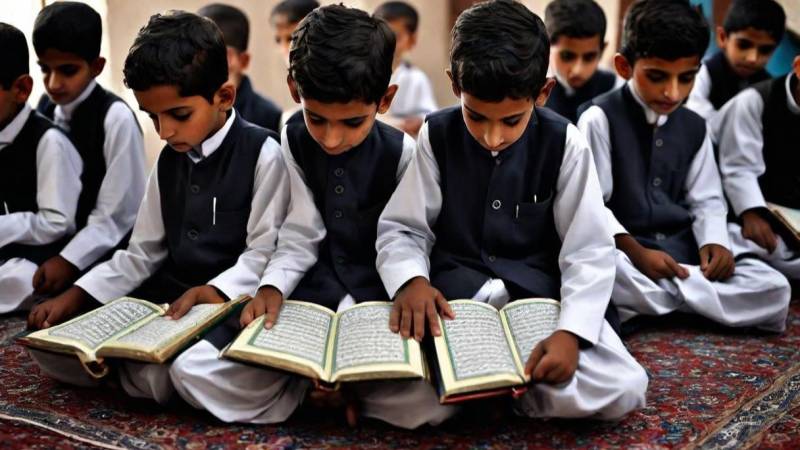

The story of madrassahs, which arose as a response to British rule, begins less than a decade after the 1857 War of Independence. In 1866, South Asia witnessed the establishment of the first madrassah that sowed the seeds of a brand of revivalist Islam. Sunni in its orientation, this Deoband madrassah was the first of many that would soon spring up across the subcontinent. With Mughal rule disbanded and English common law given prevalence over Sharia rulings, Muslims of the subcontinent had a newfound interest in producing Islamic literature and imparting Islamic education, as they felt an urgent need to preserve their identity against the displacing currents of colonial rule.

For the colonisers, their primary concern was not the education imparted to their subjects, but rather the establishment of law and order which suited their objectives. There existed an understanding between the empire and the madrassah administration that the latter would not partake in revolutionary activities, and the former would uphold the policy of laissez-faire vis-à-vis religious education. It was this understanding that allowed the Islamic landscape of the subcontinent to be diversified as different doctrinal orientations began to take root and spread among the general populace.

Vibrant religious figures associated with Darul Uloom Nadwatul Ulama were called upon to draw a vision for a potential state for Muslims

The growth of madrassahs, however, was accompanied with the consolidation of sectarian thought. This was alarming for Muslim thinkers attached to the idea of a unified Ummah. Foremost among these thinkers, Allama Muhammad Iqbal, did not shy away from criticising the indifference of English colonisers towards unregulated religious activity. He thus remarked regarding the state of religious laissez-faire:

Predictably, Iqbal's criticism did little to change the course of the Islamists or the colonialists. The madrassahs of the subcontinent continued to grow in numbers due to community support. They institutionalised the practice of charity and also provided a sense of communal belonging to Muslims whose pride was wounded by foreign rule. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan's modernised educational institutions attempted to heal the same injury. But unlike the madrassahs, they were neither as accessible nor as widespread. After all, the modernists were few, while the Islamists were numerous.

A bridge between the Modernists and Islamists was to be drawn, and that is why Jinnah, a pragmatic spokesperson of the Muslim League, was not above engaging with the "madrassah crowd" for the success of the Pakistan movement. He recognised that many Muslims of the subcontinent had links with madrassahs and had traced their social and political identity through education imparted at these institutions. Thus, vibrant religious figures associated with Darul Uloom Nadwatul Ulama were called upon to draw a vision for a potential state for Muslims. Pir Syed Jamat Ali Shah of the Naqshbandi order declared Jinnah "a saint sent by God himself" to his students. Jinnah's political manoeuvring worked a little too well, as evidenced by an anecdotal interaction a Muslim League worker had in a village where he reported that people thought the Quaid-i-Azam was "a big moulvi with a long beard".

Whether a unification akin to Jinnah's can occur between left-wing and right-wing factions today remains uncertain, but it does hold great potential for Pakistan's advancement. While progressive factions are prone to view madrassahs as archaic institutions, it is still worth noting that madrassahs are remnants of the legacy of anticolonial struggle, and a formidable chunk of the Muslim population still identifies with them. However, negative attitudes towards madrassahs will prevail unless the Madrassah Administration takes steps to denounce affiliations with extremist elements. Until they do so, their past of anticolonial struggle will continue to be overshadowed by present-day exploits.