Many Pakistanis have a medieval mindset. They believe things can change by changing the "King" or some of the big players on the grand chessboard of power politics. A change of faces will not make any difference, because the country has suffered from poor management of the economy for the past two decades, regardless of who was in power.

The dream merchants and carpetbaggers thrive on selling stories - promising miracles like bringing looted wealth back or billions in foreign investments. However, economic progress is not about miracles. It is about capable leadership and good governance. No political party or leader has given a program to reduce the crushing and rising debt burden, currently increasing at a rate of about $2 billion a month. This is why taxes will keep increasing and there will be little relief for 99% of the people.

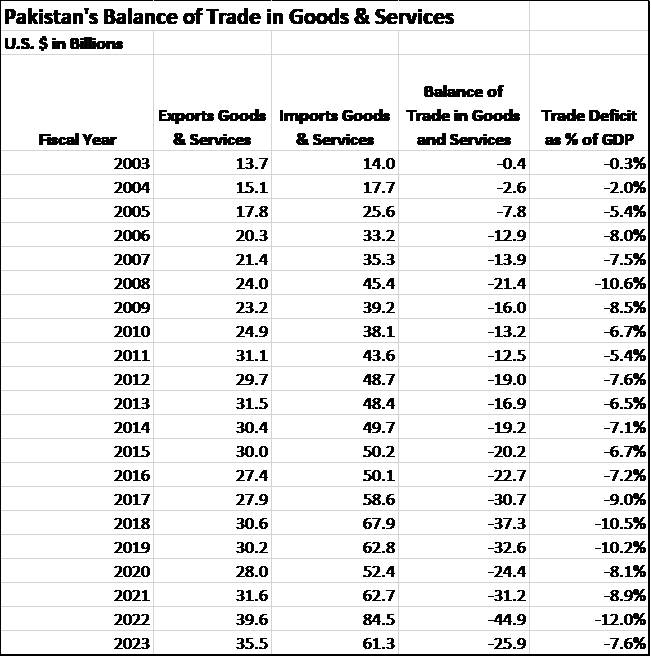

The finance minister claims that Pakistan's economy is on the right track, citing a current account surplus of $491 million in April 2024. The deficit for the first ten months of the fiscal year, ending in June, was just $202 million. This follows a pattern of familiar economic cycles in Pakistan: import-driven growth, balance of payments crisis, IMF bailout, stabilisation, recovery, growth, and then back to crisis. Pakistan had a current account surplus of $424 million in July 2020. What happened thereafter is history.

The Impact of Economic Performance on the People

The economic performance of a government has a direct impact on the populace, with the current account deficit—a measure of the difference between external receipts and payments—being the most critical indicator for a country like Pakistan which is heavily dependent on imports, especially energy. Large deficits have led to depleted foreign exchange reserves, currency devaluation, and high inflation.

The Musharraf Era (2002-2008)

During Musharraf's tenure, Pakistan's economy performed relatively well. From 2003 to 2007, the country enjoyed current account surpluses, peaking at $4.1 billion (3.6% of GDP) in FY2002-2003. However, the financial year 2007-08 was marked by multiple crises, including the lawyers’ movement, Benazir Bhutto's assassination, general elections in February 2008, and global financial and energy crises.

The PPP Government (2008-2013)

After the PPP took over in March 2008, the current account deficit hit a record low of 6.9% of GDP for the financial year 2007-08. However, the PPP government was so preoccupied with the political crisis that it underestimated the gravity of the economic situation. It delayed going to the IMF hoping (wrongly) the United States and other friends would bail out Pakistan. Ultimately, Pakistan went to the IMF for a $7.6 billion loan in November 2008.

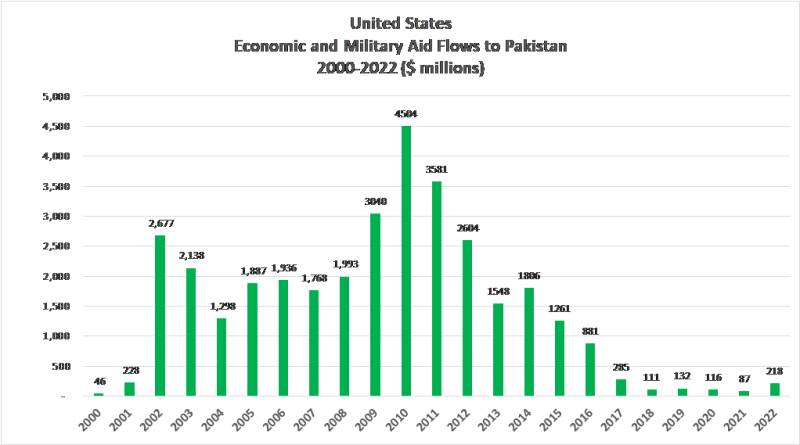

Despite an increase in U.S. aid, economic growth plummeted post-Musharraf, exacerbated by record oil prices in 2008 and devastating floods in 2010.

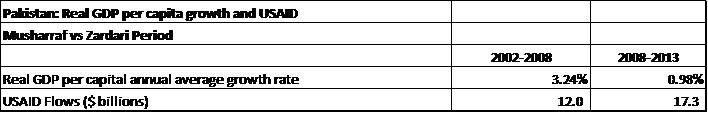

The annual average real GDP per capita growth rate was 3.24% during 2002-2008 and just 0.98% during 2008-2013. The flows of American aid continued to grow even after Musharraf left and it is difficult to argue that the weak performance of the PPP government compared to Musharraf’s period was mainly because the military regime received generous aid.

The economic and military aid flows from the United States during the years 2010-2011 were higher than in any year during the previous decade.

The PML-N Government (2013-2018)

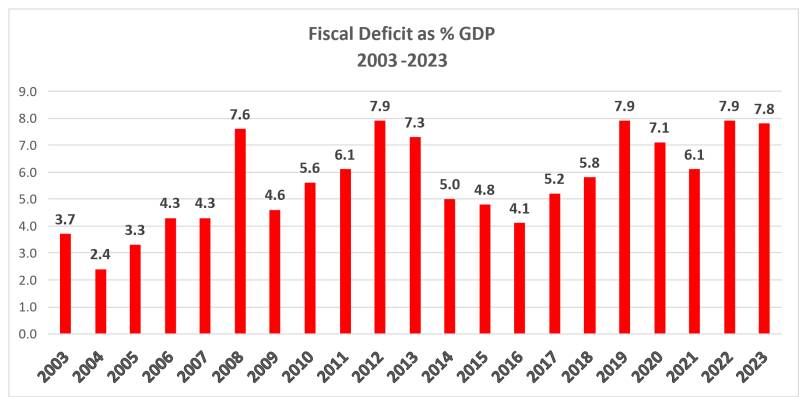

Upon assuming power in 2013, the PMLN secured a $6.6 billion IMF loan. While it reduced the budget deficit, the external front, particularly exports, fared poorly. The worst current account deficit since 2008 occurred in FY2017-18, reaching 5.4% of GDP ($19.2 billion). This was primarily due to economic policy rather than an international oil crisis or some other external shock.

The historic reason for Pakistan’s worsening trend in its current account is its chronic inability to earn (exports) more than it consumes (imports). The difference between the two – the balance of trade – has deteriorated over the past 20 years regardless of which government was in power.

The PTI Government (2018-2022)

The PTI inherited a large current account deficit in August 2018. Although the deficit was reduced to 1% in 2020-21, mainly by reducing imports rather than growing exports, it surged again in the second half of the year, reaching $9.2 billion in the first six months of FY2021-22. The full-year deficit was $17.5 billion (4.7% of GDP). Additionally, the fiscal deficit rose to over 7% of GDP in FY2018-2019 and FY2019-2020. Pakistan faced a double whammy of a high current account and fiscal deficit under the PTI government.

The PDM/PML-N Government (2022-2024)

The PDM government faced a severe currency crisis upon taking office in April 2022, leading ultimately to an IMF bailout of $3 billion. The foreign exchange reserves fell dramatically, and the currency depreciated sharply, taking the country to the brink of default in the summer of 2023. PDM (led by PML-N) government’s weak management contributed to the worst currency crisis in 50 years and it was therefore partly responsible for the record inflation in 2023, notwithstanding the commodity price shock after the Ukraine war.

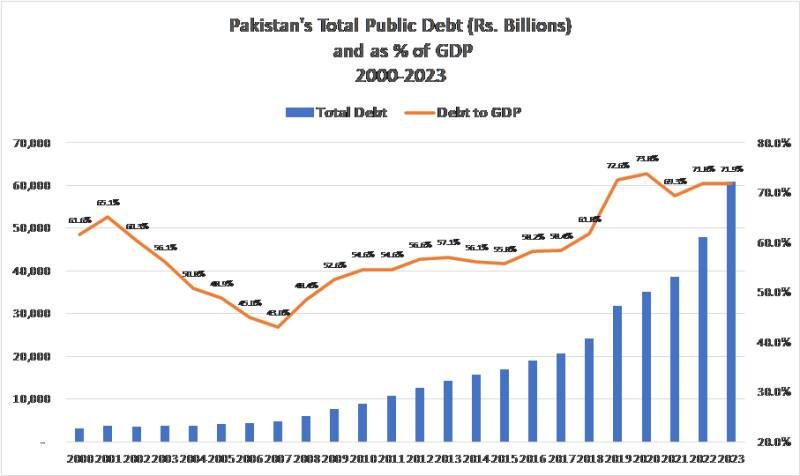

Debt and Borrowing Trends

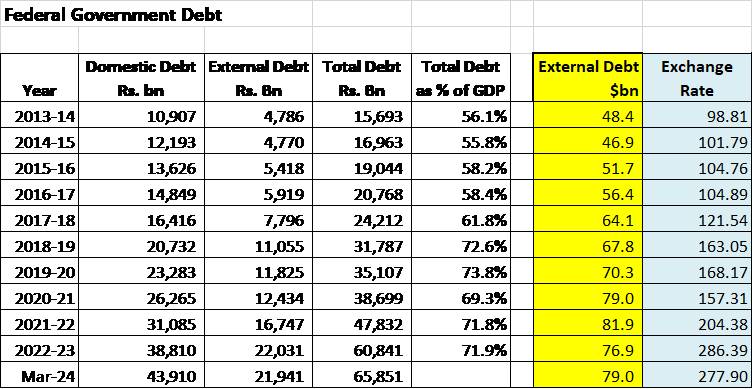

Pakistan's public debt to GDP ratio improved steadily from 2000 to 2007, from 61% in 2000 to 43% in 2007. It then climbed to 57% in 2013 and hit a new peak of 73.8% in 2020. The biggest jump during a single year (during the last decade, before the COVID-19 and 2022-23 energy crises hit Pakistan) in the public debt, came in 2019 when the total government debt increased by Rs 7.57 trillion and the domestic debt by Rs. 4.3 trillion. The debt-to-GDP ratio climbed to 72.6% in 2018-19 from 61.8% in 2017-18. This was caused in large measure by loans obtained under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Program (CPEC) as well as due to 25.5% currency devaluation. At the end of FY2022-23, the total public debt was Rs.60.8tr and 71.9% as a proportion of the GDP.

This table shows the evolution of government debt from 2013-14 to 2024. Federal government debt doubled between 2017-18 to 2021-22, according to the official data available on the State Bank of Pakistan’s website. The PTI government took the government debt to the highest ever levels.

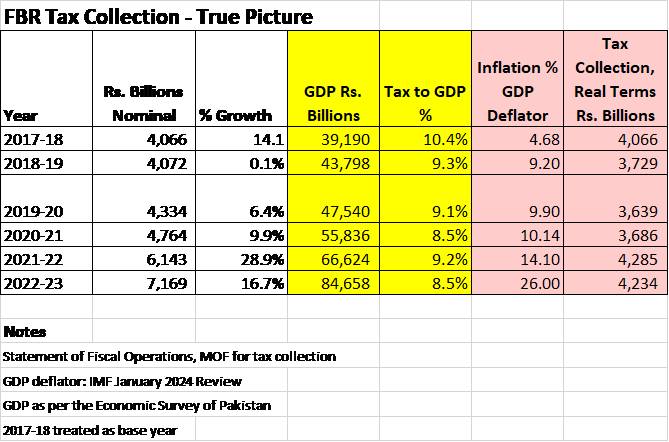

Tax Revenues under the PTI’s government

While the PTI inherited a worsening external account situation, it is also a fact the tax revenues in real (inflation-adjusted) terms went down by 11% in just two years after the PTI government took over in August 2021. It resorted to record borrowings. The big rise in the local debt came before the pandemic and the record currency devaluation in 2022-23.

Aid from the United States and China

US aid flows, totalling $33 billion from 2002 to 2016, were not loans and did not increase Pakistan's debt burden. In contrast, Chinese aid, primarily in the form of project loans, has significantly contributed to the rising debt.

Summary of past economic performance

The reality is more complex and nuanced than some political and economic analysts would like to believe.

Overall, the economy performed better under Musharraf than under subsequent governments. The fiscal management was much better despite its political blunders. The PPP managed the current account better than generally acknowledged but struggled with economic growth and fiscal governance.

The PML-N government oversaw the worst external account crisis despite achieving better growth compared to the PPP. It was obsessed with the idea of building infrastructure with foreign debt – a recipe for disaster as many developing countries have learned the hard way.

The PTI failed to grow the tax revenues and borrowed heavily to finance budget deficits. The PTI also failed to stop the current account deficit that went out of control in 2021.

The PDM (led by PML-N) government’s weak management and internal power struggle contributed to the worst currency crisis in 50 years and it was therefore partly responsible for the record inflation in 2023, notwithstanding the commodity price shock after the Ukraine war.

The Chinese did help in some building some infrastructure projects but those imposed a crushing debt burden on Pakistan and created even bigger problems. The USAID consisted mainly of non-debt-creating flows and their economic impact was better than was generally believed.

What’s ahead? Near term outlook

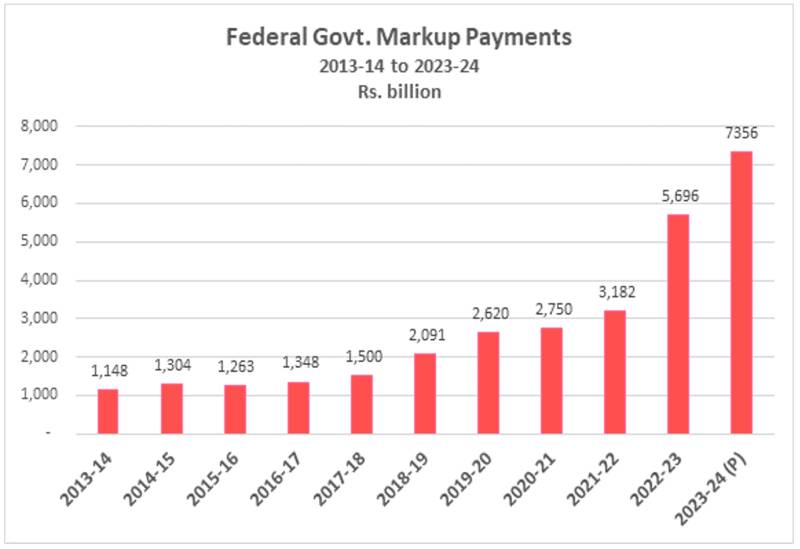

Many believe that the federal government’s fiscal deficit can be managed by just cutting some expenses or by reducing the payments made to the provinces under the NFC award. Perhaps some adjustments can be made but those will not be enough to make a major dent in the deficit due to the staggering rise in the markup payments which more than doubled in just two years from FY2020-21 to FY2022-23 due to high interest rates and the impact of the currency devaluation.

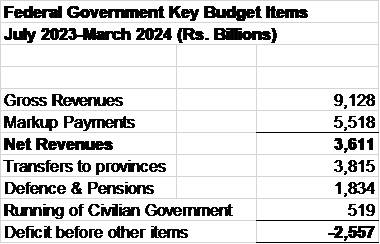

To illustrate this point further, let’s examine the federal government’s key revenue and expense numbers for the first 9 months of FY 2023-24.

The total revenues of the federal government were Rs. 9.1 trillion, and just Rs.3.6 trillion after making the markup payments of Rs 5.5 trillion. The markup payments are projected to cross Rs7.5 trillion for the current financial year and close to Rs 9.7 trillion for the next financial year of 2024-25.

Therefore, it is unrealistic and unreasonable to make the case that we can address the issue by just cutting some expenses. The government should try to save and cut expenses but that alone won't be enough given the huge level of debt servicing involved.

Even if the transfers under the NFC award are reduced, as some suggest, it won't fix the debt problem. The country may need to restructure the debt, increase tax revenues or do both. What it means for the vast majority is that their suffering is likely to continue for many years to come due to huge debt levels and an economy that is unlikely to grow at a rate which would bring some relief to the people.