Stop all the clocks ... let the mourners come.

(WH Auden)

April 10 earlier this month marked the birth centenary of the late Hamza Alavi. While the world-renowned Marxist sociologist does not need an introduction here in South Asia, my reflections here will chiefly consist of my memories of my lone meeting with him in the last years of his life, before reflecting a bit on how that meeting changed me both professionally and politically, and concluding with the relevance of his work for our own times, chiefly Pakistan.

I cannot help but compare Hamza Alavi’s legacy with another towering intellectual who like Alavi was a rootless cosmopolitan, uprooted from his country of birth, made his professional name in the West both as a distinguished scholar and as an activist, was vilified and shunned by the orthodoxy but unlike Alavi, was denied the satisfaction of passing away in his native land. I am talking, of course, of the late Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, who like Alavi also passed away in 2003. Both Said and Alavi, in their own distinct ways, one as a literary critic and the other as an anthropologist/sociologist, strove to defend the oppressed and marginalized, and investigate the cultural structures which gave birth to such oppression and to attempt to challenge them. Both of them were marked by seminal events in their lives: Said by the 1967 Arab defeat to Israel, and Alavi by the liberation of Bangladesh, which dismembered Pakistan, a few years later, in 1971. Yet one also cannot help note the irony that while Said’s legacy continues to be celebrated worldwide from Ramallah and Beirut to New York and London, who but a few prominent devotees (in the East) choose to dwell on Alavi’s contributions, but not in the West, a hundred years on?

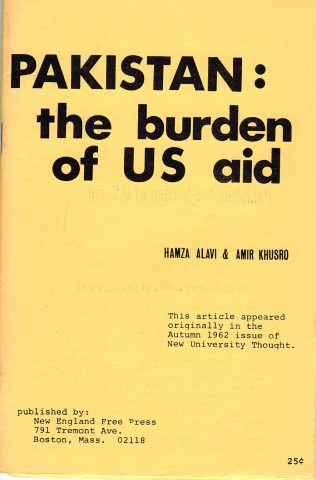

As we remember Hamza Alavi a hundred years after his birth, one often wonders what he might have felt and written about some of the things which have been happening in the world since his death. He was not a passive witness to 9/11 but, for example, what would he have felt about the meteoric rise of Islamophobia and Western imperial campaigns in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and the ongoing fracturing of Syria? Or the rising sectarian intolerance and religious fundamentalism that has characterized Pakistan – and indeed increasingly now India and Bangladesh as well – and appears bent on consuming it? Or Pakistan’s imperfect transition to democracy following an equally imperfect military dictatorship? More poignantly, as I write this, Pakistan’s Prime Minister has indicated that he would approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a second relief package, coming at the heels of a US$ 6 billion loan already secured from the IMF in 2019; something Alavi presciently foresaw in a series of essays on Pakistan’s dependence on US aid and military cooperation as early as the 1960s. Or that a highly disciplined peasant army under Maoist leadership would topple a centuries-old Hindu royal despotism ushering in a secular republic in tiny Nepal. And what would he have made of China next door, where capitalist restoration and the rampant inequality and corruption that it has spawned in its wake is beginning to be countered by a New Left intelligentsia once again in thrall to Marx and Mao? Or indeed the rising tide of honour-related crimes against Pakistani women rooted in patriarchy and obscurantist religion and the rise of a barely-teenage girl named Malala Yousufzai, who has become a symbol of resistance against creeping Talibanization in the time of drone attacks and gone on to win the Nobel Peace Prize; and even the rise of a nascent middle-class, sections of which for its own reasons ended up supporting Pervez Musharraf, then the successful lawyers’ movement, and later Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf, and the weakness of the Pakistani Left?

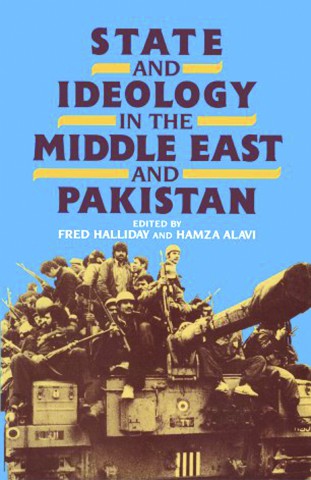

In many ways, Hamza answered these and other questions in his seminal essays on imperialism, socialism, the contours of the postcolonial state, the role of peasantry in revolution, state and class in Pakistan, the contradictions of the Green Revolution, Pakistan’s dependence on US aid, and the anthropology of biradiri. Reading and rereading these essays today still considerably repays the attention needed in these troubled times, while for others the new times we live in as well as the changing nature of imperialism and structures of state and society in the developing countries demand a reappraisal and creative critique of his work.

I was introduced to Hamza Alavi as an apathetic product of a typically privileged, private-school educated middle-class milieu, not uninterested in the world, as an economics undergraduate at the Lahore School of Economics in the last few years of the 1990s. I remember our sociology instructor starting the discussion on Alavi’s seminal paper on class and state in Pakistan by referring to him as a “rather grumpy old man.” That was enough for most of my peers to be kept away from Alavi’s work for life! I, however, hung on, and later carried my enthusiasm in the form of a mini-rebellion against three years of studying neoclassical economics by taking up Development Studies as my postgraduate major at the University of Leeds, which I later discovered had been the site of some of the most fulfilling years of Alavi’s professional life. There I was taught by one of Alavi’s students, a very fine instructor and later chose to write my dissertation on state and class in Pakistan, influenced by Alavi’s work. In Leeds during 2002, I emailed Hamza introducing myself and requested him to see me when I came to Karachi later in the summer that year to conduct some interviews for my research. Not used to Pakistani professors going out of the way to help their students, while those in the West took this privilege for granted, I was shocked, when in a couple of hours, Hamza emailed his response encouraging me to see him. I remember being so overjoyed that early morning the next day, while auditing a class on Middle Eastern politics, I boasted to my Development Studies classmates about hearing back from one of the intellectual giants in the field, and all my classmates who had undoubtedly heard of Alavi’s work, complimented me on my good fortune!

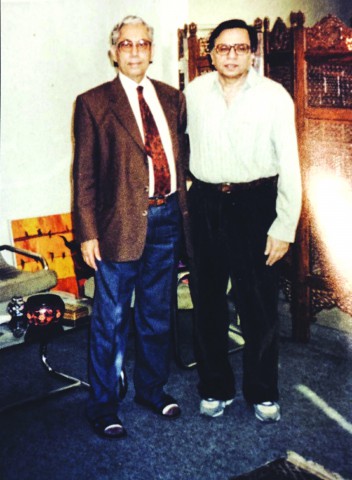

Back in Pakistan for research in the summer, I knew Hamza was in failing health and when I attempted to remind him over the telephone of his earlier promise to see me, he express inability, to my great disappointment. However, when my father in his matter-of-fact ex-government servant’s tone persuaded him, he agreed to see me, and I flew to Karachi in July/August to see him at his elegant Gandhi Gardens residence, clad in immaculate white kurta pajama. What followed was a couple of hours of a sophisticated exposition on the class structure of Pakistan, and suggestions for future research. Back in Leeds, I added to my instructors’ knowledge of Hamza Alavi by informing them that Hamza was in fact alive, and not deceased, as they had been presuming all along!

I moved on from Alavi’s analysis of the role of the mediating classes in his seminal 1972 article on The State in Postcolonial Societies (published in the New Left Review) to Marxist theorist Nicos Mouzelis’s book Politics in the Semi-Periphery, published a decade later. My unpublished thesis titled “Neither Tragedy Nor Farce: The Contradictions of Bourgeois Democracy in Pakistan” extends Alavi’s analysis by attempting to explain why democracy – and more specifically bourgeois democracy – has historically never flourished in Pakistan. It primarily utilizes the Marxist construct of peripheral capitalism, as elaborated by political scientist Nicos Mouzelis in his book, Politics in the Semi-Periphery (1983) and Leon Trotsky’s definition of Bonapartism in late-industrializing societies to explain this phenomenon. The research has concluded that the primary reason why bourgeois democracy has failed to strengthen itself in Pakistan is because the state had a very weak industrial bourgeoisie to begin with at the time of its inception in 1947, which was why they were neutralized by powerful unelected institutions like the army, the landed elite and the civil-military bureaucracy. Later, when a nascent bourgeoisie did consolidate itself, the contradictions of uneven development forced the state to not only halt this consolidation, but to seek to placate the interests of competing classes. Then, despite a firm democratic mandate in 1971, the contradictions of late capitalism ensured that the Pakistani state under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto played the classic Bonapartist role, with the industrial bourgeoisie being forced to pay a heavy price because of their relative isolation and relative weakness as a political power. Despite closer integration of Pakistan’s ruling elite with world capitalism and imperialism in recent times (especially post-Zia), the bourgeoisie are still weak in Pakistan which explains their ideological insecurity and the frequent resort to Bonapartism and clientelist politics (during the 1990s, continuing with Musharraf and restoration of democracy in 2008). If the promise of late capitalism is to be realized in Pakistan, then such a Bonapartist state will have to consolidate the bourgeoisie as an established force; only then can conditions of a stable bourgeois democracy emerge in Pakistan, with the bourgeoisie playing a role which they have already performed nearly four decades ago in other post-colonial countries – the development of a local market, ending autocracy and holding parliamentary elections guaranteeing a bourgeois democracy based on socio-economic justice. That is why Pakistan today appears close to 18th-century France as described by Karl Marx in his 18th Brumaire. I’m now anxious to publish this as a book before the next military coup in Pakistan!

I always wanted to return to Pakistan to strive to do for the country what Hamza had done most of his life as an unwilling exile abroad. This desire was sharpened by my acquaintance with Pakistan’s nascent communist movement during my undergraduate years in Pakistan and politicized by my encounters with Arab friends and comrades in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 in Leeds and the stifling heavy-handedness of the Musharraf years when I returned home. Hamza’s initial forays into the State Bank of Pakistan encouraged me to make a relatively quick transition from an unhappy year as a firebrand lecturer in political science at Government College University in Lahore to my own apprenticeship at the State Bank in Karachi. After spending four fulfilling years in Karachi – but not at the Bank, where I served in the Inspection and Research Departments and finally the Corporate Secretary’s Office – I also reached the unhappy conclusion that it was easier to sustain the life of the mind and the activist while being outside the Bank than inside, by making a return to academia. Unfortunately, too many of the Bank’s former governors have reached just the same conclusion! So thank you Hamza for setting up an example that we could also follow successfully.

Over the years, I have often thought about my lone encounter with Hamza Alavi back in 2002, just a year before he passed away, and have come to cherish its memories deeply. This has allowed me to think more thoroughly about the relevance of his work, especially on post-colonial societies. As I have tried to show very humbly in my own work, the Bonapartist role did not remain confined to Bhutto, the baton was passed to Musharraf who played the role more successfully than the former. One also needs to take into account the awakenings of Pakistan’s middle class and the fact that the bourgeoisie are still weak in the country, unlike in neighboring India, thus perpetuating the need for mediation. Also, Pakistan is a far more urbanized society than it was in Hamza’s time as the work of Reza Ali has shown; therefore the debate over whether feudalism is still the dominant mode of production in Pakistan needs to be re-approached, as well as the fact that the military may have taken a back seat in derailing democracy for now, but it is simultaneously the biggest landlord and capitalist in the country, albeit challenged by powerful social movements in Punjab and Sindh, and increasingly now in the Pashtun heartlands in the form of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement.

I also think Hamza’s work on postcolonial societies could be useful for understanding some Arab societies in transition after the fall of dictatorships there, especially in ‘advanced’ peripheral capitalist societies like Egypt, where a similar coterie of the army and civil-military bureaucracy mid-wifed by the United States seems to be in charge, albeit without the control of landlords (due to the land reforms of Nasser) which has so hampered Pakistan’s socio-economic development.

Hamza Alavi was truly an intellectual giant of Pakistan. That he was never awarded any indigenous medal or recognition for his tremendous scholarship probably adds to his reputation. It in fact reflects the plight of those in Pakistan, for whose cause Hamza Alavi fought throughout his life, that they are still impoverished and hopeless in modern Pakistan - what Karl Marx would call the have-nots.

In the end I would like to finish with what Hamza Alavi’s intellectual mentor Karl Marx once said should be the role of every thinking person, “The philosophers have only understood the world, the point however is to change it”. Whatever the shape of modern tempmail day Pakistan, I know for a fact that Hamza was one of those same thinking people who not only understood the world, but sought to change it as well (he was one of those about whom is said in Arabic as the ahl al-hal wa al-aqd).

Interestingly, back in October 2013, a mere decade after Alavi’s death, when the legacy of the late Ralph Miliband, one of Hamza’s great comrades in the UK and an important Marxist theorist and critic of capitalism, came under attack by a right-wing rag The Daily Mail, Miliband’s younger son Edward, one of the leading lights of the British Labour Party, gave a spirited response defending his father. The affair was entertaining not because the Labour Party, especially under the Miliband brothers had long ceased to be the socialist party of the oppressed that Miliband senior’s politics had always envisaged it to be, but that it led to a great spike in the interest in Miliband senior’s classic books on parliamentary socialism and the capitalist state.

I wonder: though Hamza did not have any biological progeny of his own, how could interest in his own distinguished work be resuscitated here in Pakistan almost two decades after his death now, compared to the Miliband affair which had occurred too within twenty years of Ralph Miliband’s death?

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader based in Lahore, where he is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association. He is currently working on a book ‘Sahir Ludhianvi’s Lahore, Lahore’s Sahir Ludhianvi’, forthcoming in 2021. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com