The Wilsonian peace thesis grounded in Kantian ‘perpetual peace’ could not end wars and armed conflicts due to institutional and operational lacuna that the world leadership overlooked owing to divergent interests. Hence, the complexities of political economy in the aftermath of World War I widened political and policy differences among the transatlantic power hubs. The world, tragically, witnessed another world war that affected power relations globally as well as regionally.

The US emerged as a ‘new’ hegemon. It replaced the British not just geopolitically but also commercially. Even institutionally, the US initiated organisational processes amid the World War II that culminated in the formation of the Unites Nations and the proverbial Bretton Woods institutions, i.e. the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

Within a few years post-WWII, the US and USSR, which cooperated in the said war, parted ways. They expanded their strategic influence in initially Europe and ultimately in other parts of the world, particularly Asia. Europe felt tremors of Cold War (simply put: no peace, no war) in terms of Berlin Blockade (1948-49), formation of NATO in 1949 and consequent arms race between the US and USSR.

Regionally, the Cold War geopolitics engulfed a whole range of countries whose majority got independence from the European colonisers after the WWII. Interestingly, however, Iran (called Persia before 1935) and Saudi Arabia (became a sovereign state in 1932), both Gulf countries from what is called the Middle East (West Asia), escaped colonisation in the traditional sense. Though the British influenced regimes in both the countries during the first half of the 20th century. However, as already argued, post-WWII, the US became a dominant power within the Middle East as well. Iran and Saudi Arabia (both were monarchies) allied with the US for military and economic reasons.

Staunch supporters of Imam Khomeini, who devised a new political concept known as Vilayat al-Faqih (rule of jurist), toppled the monarchy in Iran in 1979. Khomeini, who led the anti-Shah movement from Europe, finally joined his people in order to establish an Islamic system of state and governance based on Shiite interpretation of Islam with reference to Vilayat al-Faqih. Geopolitically and ideologically, it was a significant development for the Saudi monarchy that was based on the Salafist interpretation of Islam with respect to governance and jurisprudence.

The Saudis seemed suspicious of the Iranian regime, which, in their view, could disseminate its “revolution” and religious interpretation in other parts of the Middle East. Thus, a sub-regional Cold War started between the Saudi-led bloc that comprised Pakistan and the Iran-led camp, which included various militant groups from Lebanon, Palestine and nowadays Syria and Yemen. Globally, the Khomeini-led Iran challenged the US hegemony particularly in the Middle East where the US and its NATO allies provided military and economic support to Israel consistently.

Khomeini-led Iran otherised Israel as a major threat to its existence as a sovereign state. The Iranian leadership bracketed Saudi Arabia with Israel as an American pawn working against the Iranian interests in the region. The Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s demonstrated, on one hand, regional rivalries among Iran, Saudi Arabia and Israel and, on other hand, between Iran and the US-led allies globally. In fact, the US sanctioned Iran on multiple occasions in the hope of a regime change. However, it could not materialise, owing to strong ideological apparatuses that the Iranian theocracy has established since its inception in 1979.

Thus, there was little improvement in Saudi-Iran ties in the 1980s. Their relations remained strained in 1990s and 2000s. Institutionally, Iran could not join the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) since its establishment in 1981 due to the Saudi influence. The OIC is also Saudi-dominated where Iran’s presence is only marginally visible.

However, Iran has, over decades, learned the art of strategic manoeuvring through various measures, such as the use of militia against archrivals in the region. The US war in Iraq generated another context that the Iranian authorities used to their advantage in terms of moral and military support to pro-Iran factions in Iraq, Syria and other regional proxies. Indeed, Iran has tussled with Saudi Arabia in Yemen for past many years. Ironically, despite a strong military, the Kingdom has fumbled to win its war in neighbouring Yemen, where hundreds and thousands have been killed, and millions have been displaced, due to Saudi-Iran tussle.

In 2020s, owing to economic cost of the unresolved Yemen conflict, coupled with the Saudi desire to diversify its economy under Mohammad bin Salman’s Vision 2030 in a relatively peaceful regional setting, where China has marked its economic footprints under its Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI), the Kingdom opted for negotiations with Iran.

At its part, Iran also needs space to stabilise its economy and society. Only recently, the youth agitated in different parts of Iran to demand rights to freedom of association and speech.

From China’s perspective, for trans-regional trade and economic cooperation, particularly with Iran, where the former committed US $400 billion in Iran in 2021, a conflict-free regional environment is but necessary. Being rational stakeholders, Saudi Arabia and its GCC partners would desire the same since China has also invested considerably in Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar and, importantly, Israel. Both Iran and Saudi Arabia export petroleum products to China.

For uninterrupted supply chains and domestic growth in these countries, regional peace is a must. The Kingdom supported its Gulf ally, the UAE, to establish diplomatic ties with Israel. It also opened its air for Israel flights recently. Being a rational actor, Israel needs more markets for economic reasons.

As far the US is concerned, it has already shifted its strategic interest to Southeast Asia. The Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (ARIA) and related policy procurements are a case in point. Nonetheless, being a key regional player, the US would keep its tactical presence in the region through its military basses. A relatively non-violent Middle East is likely to serve the American interests as well. The latter can focus on, for example, South China Sea than consuming resources in the Middle East. To this end, the US supported dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia through Iraq and Jordon under the Biden Administration.

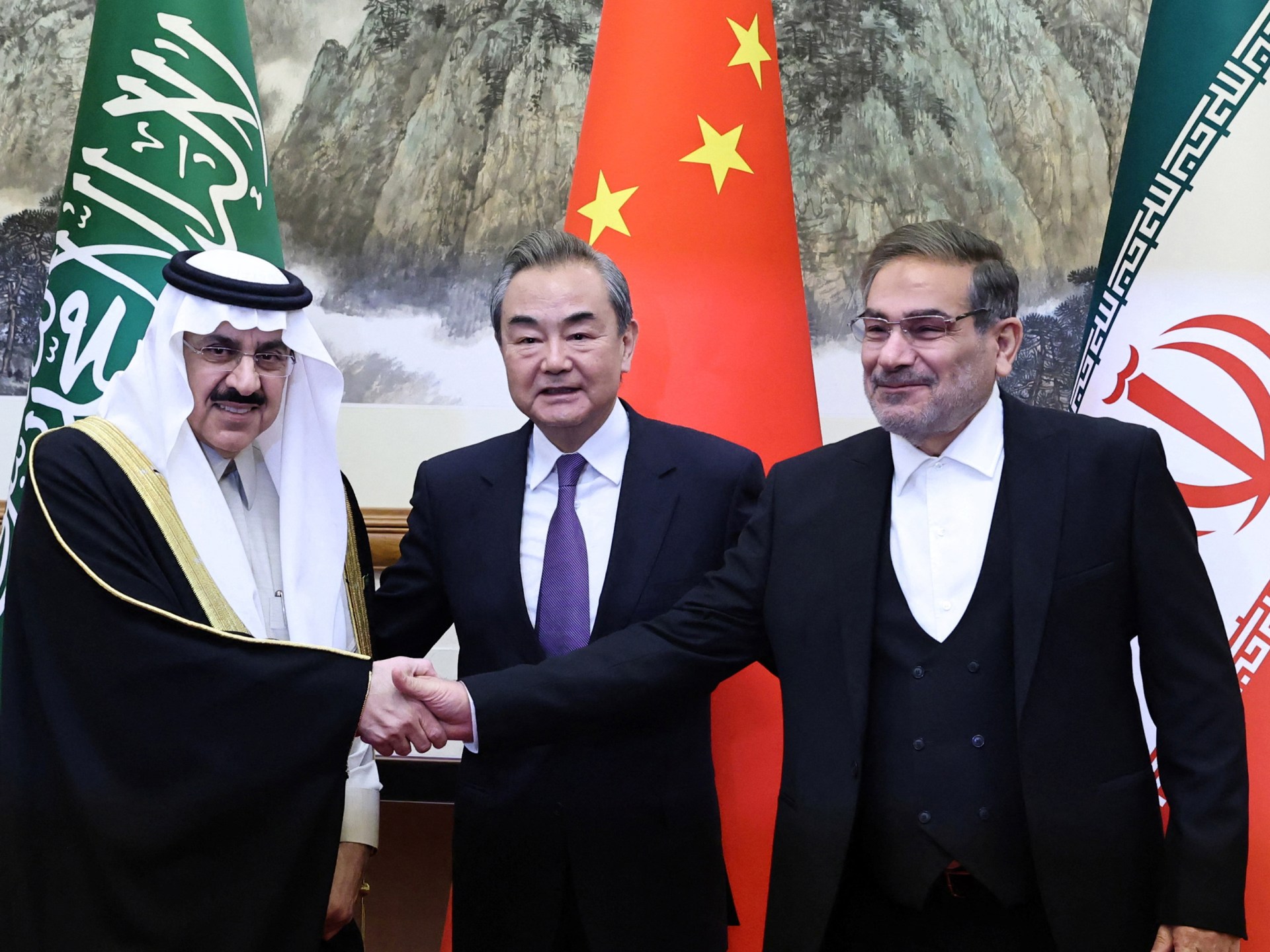

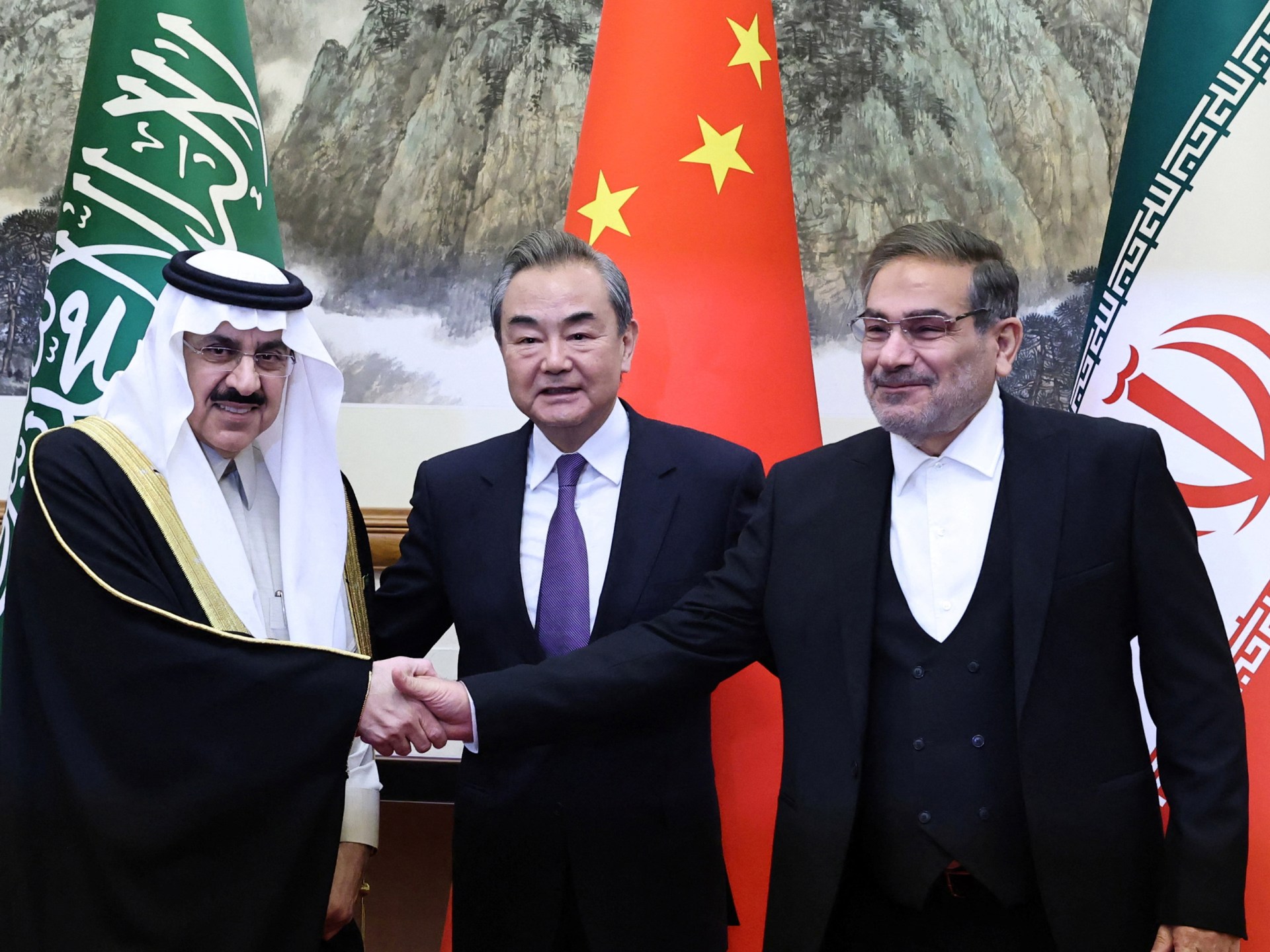

However, since there has been a change in the government in Iraq and the US is busy in the Russia-Ukraine war, China has got an opportunity to play a lead role in terms of encouraging and hosting in camera talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia in recent months. From a neo institutionalist perspective, it is in the mutual interest of the two countries to prefer peaceful co-existence by establishing regimes and institutions, such as the free trade agreements. Additionally, the Saudi-Iran detente offers economic incentives to not only China but also other regional countries, such as the UAE and Qatar.

As far as Pakistan is concerned, it may not be a direct beneficiary of this détente in the short run. Pakistan may feel some of the trickle down effects of the normalisation between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the two archrivals that have affected the social, economic and political fabric of the country not just during the Cold War but in the 21st century as well. From sectarianism to one-dimensional foreign policy, Pakistan remained a hostage of its lop-sided strategic calculus. Pakistan’s internal problems, especially economic vulnerability, have hugely impacted its foreign policy. Even after 76 years, Pakistan suffers from structural compulsions.

Theoretically, the Saudi-Iran detente offers a room to Pakistan to strengthen economic relations with Iran – say, by resuming work on Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project. However, because the Saudi resentment has been subdued post-rapprochement, Pakistan will find it difficult to put it into practice, given its conventional reliance on the US-led world (economic) order. Will the US nod Pakistan to reap dividends of Saudi-Iran detente is yet to be seen. But China will encourage trans-regional trade and economic cooperation – a hallmark of the BRI.

The US emerged as a ‘new’ hegemon. It replaced the British not just geopolitically but also commercially. Even institutionally, the US initiated organisational processes amid the World War II that culminated in the formation of the Unites Nations and the proverbial Bretton Woods institutions, i.e. the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

Within a few years post-WWII, the US and USSR, which cooperated in the said war, parted ways. They expanded their strategic influence in initially Europe and ultimately in other parts of the world, particularly Asia. Europe felt tremors of Cold War (simply put: no peace, no war) in terms of Berlin Blockade (1948-49), formation of NATO in 1949 and consequent arms race between the US and USSR.

Regionally, the Cold War geopolitics engulfed a whole range of countries whose majority got independence from the European colonisers after the WWII. Interestingly, however, Iran (called Persia before 1935) and Saudi Arabia (became a sovereign state in 1932), both Gulf countries from what is called the Middle East (West Asia), escaped colonisation in the traditional sense. Though the British influenced regimes in both the countries during the first half of the 20th century. However, as already argued, post-WWII, the US became a dominant power within the Middle East as well. Iran and Saudi Arabia (both were monarchies) allied with the US for military and economic reasons.

Staunch supporters of Imam Khomeini, who devised a new political concept known as Vilayat al-Faqih (rule of jurist), toppled the monarchy in Iran in 1979. Khomeini, who led the anti-Shah movement from Europe, finally joined his people in order to establish an Islamic system of state and governance based on Shiite interpretation of Islam with reference to Vilayat al-Faqih. Geopolitically and ideologically, it was a significant development for the Saudi monarchy that was based on the Salafist interpretation of Islam with respect to governance and jurisprudence.

As far as Pakistan is concerned, it may not be a direct beneficiary of this détente in the short run. Pakistan may feel some of the trickle down effects of the normalisation between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the two archrivals that have affected the social, economic and political fabric of the country not just during the Cold War but in the 21st century as well.

The Saudis seemed suspicious of the Iranian regime, which, in their view, could disseminate its “revolution” and religious interpretation in other parts of the Middle East. Thus, a sub-regional Cold War started between the Saudi-led bloc that comprised Pakistan and the Iran-led camp, which included various militant groups from Lebanon, Palestine and nowadays Syria and Yemen. Globally, the Khomeini-led Iran challenged the US hegemony particularly in the Middle East where the US and its NATO allies provided military and economic support to Israel consistently.

Khomeini-led Iran otherised Israel as a major threat to its existence as a sovereign state. The Iranian leadership bracketed Saudi Arabia with Israel as an American pawn working against the Iranian interests in the region. The Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s demonstrated, on one hand, regional rivalries among Iran, Saudi Arabia and Israel and, on other hand, between Iran and the US-led allies globally. In fact, the US sanctioned Iran on multiple occasions in the hope of a regime change. However, it could not materialise, owing to strong ideological apparatuses that the Iranian theocracy has established since its inception in 1979.

Thus, there was little improvement in Saudi-Iran ties in the 1980s. Their relations remained strained in 1990s and 2000s. Institutionally, Iran could not join the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) since its establishment in 1981 due to the Saudi influence. The OIC is also Saudi-dominated where Iran’s presence is only marginally visible.

However, Iran has, over decades, learned the art of strategic manoeuvring through various measures, such as the use of militia against archrivals in the region. The US war in Iraq generated another context that the Iranian authorities used to their advantage in terms of moral and military support to pro-Iran factions in Iraq, Syria and other regional proxies. Indeed, Iran has tussled with Saudi Arabia in Yemen for past many years. Ironically, despite a strong military, the Kingdom has fumbled to win its war in neighbouring Yemen, where hundreds and thousands have been killed, and millions have been displaced, due to Saudi-Iran tussle.

In 2020s, owing to economic cost of the unresolved Yemen conflict, coupled with the Saudi desire to diversify its economy under Mohammad bin Salman’s Vision 2030 in a relatively peaceful regional setting, where China has marked its economic footprints under its Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI), the Kingdom opted for negotiations with Iran.

At its part, Iran also needs space to stabilise its economy and society. Only recently, the youth agitated in different parts of Iran to demand rights to freedom of association and speech.

From China’s perspective, for trans-regional trade and economic cooperation, particularly with Iran, where the former committed US $400 billion in Iran in 2021, a conflict-free regional environment is but necessary. Being rational stakeholders, Saudi Arabia and its GCC partners would desire the same since China has also invested considerably in Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar and, importantly, Israel. Both Iran and Saudi Arabia export petroleum products to China.

For uninterrupted supply chains and domestic growth in these countries, regional peace is a must. The Kingdom supported its Gulf ally, the UAE, to establish diplomatic ties with Israel. It also opened its air for Israel flights recently. Being a rational actor, Israel needs more markets for economic reasons.

As far the US is concerned, it has already shifted its strategic interest to Southeast Asia. The Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (ARIA) and related policy procurements are a case in point. Nonetheless, being a key regional player, the US would keep its tactical presence in the region through its military basses. A relatively non-violent Middle East is likely to serve the American interests as well. The latter can focus on, for example, South China Sea than consuming resources in the Middle East. To this end, the US supported dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia through Iraq and Jordon under the Biden Administration.

The Saudi-Iran detente offers economic incentives to not only China but also other regional countries, such as the UAE and Qatar.

However, since there has been a change in the government in Iraq and the US is busy in the Russia-Ukraine war, China has got an opportunity to play a lead role in terms of encouraging and hosting in camera talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia in recent months. From a neo institutionalist perspective, it is in the mutual interest of the two countries to prefer peaceful co-existence by establishing regimes and institutions, such as the free trade agreements. Additionally, the Saudi-Iran detente offers economic incentives to not only China but also other regional countries, such as the UAE and Qatar.

As far as Pakistan is concerned, it may not be a direct beneficiary of this détente in the short run. Pakistan may feel some of the trickle down effects of the normalisation between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the two archrivals that have affected the social, economic and political fabric of the country not just during the Cold War but in the 21st century as well. From sectarianism to one-dimensional foreign policy, Pakistan remained a hostage of its lop-sided strategic calculus. Pakistan’s internal problems, especially economic vulnerability, have hugely impacted its foreign policy. Even after 76 years, Pakistan suffers from structural compulsions.

Theoretically, the Saudi-Iran detente offers a room to Pakistan to strengthen economic relations with Iran – say, by resuming work on Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project. However, because the Saudi resentment has been subdued post-rapprochement, Pakistan will find it difficult to put it into practice, given its conventional reliance on the US-led world (economic) order. Will the US nod Pakistan to reap dividends of Saudi-Iran detente is yet to be seen. But China will encourage trans-regional trade and economic cooperation – a hallmark of the BRI.