Raza Naeem, historian and translator of some of Kishwar Naheed’s works in an interview with Kala Chaupal Trust, Bulandshahr, on the occasion of her 81st birthday last month.

Aapa is a fond honorific used across South Asia (especially in the Urdu-speaking community) to denote that someone is like an elder sister in terms of her age and experience. We regard Kishwar Naheed as Aapa because she is the patron saint of not only all women in Pakistan but also the feminist movement across South Asia!

Her work is relevant because it not only reflects her own personal journey as a poet and feminist but rather more than autobiography – as I have also argued in my piece on her in The Wire which you cited – it is the voice of a whole generation which came of age in the 1960s (both during the dictatorship of Ayub Khan in Pakistan and broader currents of resistance across the Third World). In her poetry, Naheed has universalized her Pakistani identity by striving to gather together the sorrows and travails of all the women of the Third World. That is why her work is read and translated from Delhi to Buenos Aires.

Yes it is true that Kishwar Naheed was the first truly bad woman or sinful woman of Urdu poetry. But in Urdu prose her predecessors were the communist doctor Rashid Jahan (who died early) and the fearsome writer Ismat Chughtai, who was hauled before a British Indian court for addressing the theme of homosexuality in one of her stories. More recently, Naheed has had counterparts of the bad woman across other cultures and continents. One thinks of Simone de Beauvoir (whose book The Second Sex Naheed published in an abridged translation), Nawal El Saadawi (who passed away earlier this year) and the likes of Germaine Greer, Eve Ensler and Betty Friedan, etc. In terms of South Asian gender dynamics, the bad woman represents how many girls of the middle-class in traditional households were restricted, and women like Kishwar Naheed had to fight for the basic right to study further. This struggle was later reflected in various stages of freedom and expression which Naheed negotiated successfully. Naheed’s struggle gave way to other successful ‘bad women’ in Urdu poetry like Fahmida Riaz and Sara Shagufta. Today the term ‘bad woman’ has taken on a different meaning in South Asia because we are theoretically living in a modern age, but women’s rights across South Asia are being rolled back by patriarchy and conservatism. Take the case of the Aurat March in Pakistan, which has been held successfully across our major cities despite overt and covert threats, intimidation and court cases being instituted against them. The term ‘bad woman’ has become the new normal for young women in South Asia, who had taken for granted the very rights women like Kishwar Naheed had fought for. Even these rights are now being rolled back in the 21st century. But the bad women are mutiplying!

Naheed had once referenced the French poet Saint-John Perse saying: ‘My story is the story of that street woman who recites the fatiha amid sorrow, bites the wayfarers, proceeds with the prince or the dagger held in her arms.’

The term ‘bad woman’ thus denotes the modern woman whose biggest crime is her intelligence.

Oh that came about last year on Kishwar Naheed’s 80th birthday. I wanted to write a personalized tribute to her. But having already written two essays on her and being a contributor to a book of her translated poems released on her 80th birthday, I wanted to do something different. So I came across the radical Pakistani writer Ahmad Bashir’s long incendiary sketch of her which was published when she was in her 40s, just before the early death of her husband, and just starting to become notorious. It is a no-holds-barred sketch of the poet and it became so notorious that its repute spread from Lahore to London, as soon as Bashir had read it in the presence of the poet herself and her husband and Intizar Hussain wrote about it in his column. Everyone wanted to have a copy of it.

So in 2020, on Naheed’s 80th birthday, I wanted the younger generation to get to know her better, so I thought the sketch fulfils that purpose. It has been published in The Friday Times in four installments.

My only regret is that it has yet to be published in India. But I tremendously enjoyed translating it!

Well yes, any woman poet is immediately expected and stereotyped to produce poetry related to man-woman relationships or exclusively women’s issues. Many excellent Urdu poets have achieved this to perfection like Parveen Shakir, Ada Jafri and Zehra Nigah (who is still living and active); among contemporary poets you have Ishrat Afreen, Tanvir Anjum, Yasmeen Hameed, Ambreen Salahuddin, Fatema Hasan, Shahida Hasan and Azra Abbas, but Naheed has also written about other issues and continues to write about them. The circle of her poetry has been getting wider since a long time ago. Other issues she has explored in her poetry are her marital life, employment, the creation and destruction of united Pakistan, the political and social landscape and feminine sensibility, as well as some of the cardinal events of our time like the Chinese Revolution, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and 9/11. More recently, she has addressed the Donald Trump phenomenon as well as the murder of the African-American George Floyd in Minnesota last year; the growing Talibanization and Saffronization of Pakistani and Indian societies respectively; and built up a significant body of work on the COVID – 19 pandemic and its local and global ramifications. I believe that Kishwar Aapa is the most prolific and varied Urdu poet of our time!

Not really! Yes she did witness the depredations of partition as a 7-year old girl of a conservative middle-class family uprooted from her native Bulandshahr, but she quickly assimilated within the Pakistani Punjabi culture upon migration to Lahore. So partition itself does find a mention in her celebrated memoir Buri Aurat Ki Katha but it does not affect her work per se like it did her distinguished contemporaries like Intizar Hussain (also a fellow Bulandshahri), Abdullah Hussein or Quratulain Hyder. who are known for addressing such themes in their most important works. I mean Naheed is not known for her poems on partition; she hasn’t written any!

In the case of 1971, there are just a couple of chapters in her memoirs but no poetry. She has herself told me that there was a news blockade imposed by the Pakistani military dictatorship on any news coming from East Pakistan and so even when she accompanied a delegation of Pakistanis on a fact-finding mission to Dhaka at the height of the bloodbath there, she fled in horror from the carnage on a plane. So again she hasn’t really addressed this second partition in her poetry as well.

I would say it has to a certain extent, and more directly in the context of her poems from the dictatorship period of the Zia-ul-Haq regime, Pakistan’s worst military regime. Read any of her poems from that period from 1981 to 1986 and you will understand what I am talking about. Let me give the reference of just one of her poems, Mein Kaun Hoon (‘Who Am I?’), in which the echo of a whole movement can be heard which especially in the regime of Zia-ul-Haq had spread like a wave of consciousness in reaction to the trampling of women’s rights.

I think Kishwar Naheed is really lucky that she is one of the most translated Urdu poets of the 20th century, if not the most translated. As far as I know, she has been translated into most of the great languages, including for the United Nations. I can only speak for the quality of her English translations, which have been appearing regularly since 1972. They are of varying quality as is usually the case, but they have helped establish her as the representative voice of Pakistani feminism, much like you would say about Simone de Beauvoir and Nawal El Saadawi. I mean to me she is Pakistani feminism! The writer herself is actually not very satisfied with the quality of her work in translation. In my own humble translations of her work, I have consciously tried to bring out her daring political and feminist concerns, but I also believe in maintaining a certain jauntiness of ryhme.

Kishwar Naheed is identified as a distinct voice in modern Urdu poetry. Her tone is individualistic but it has the echo of the widest collective experience:

‘Meri aavaaz, mere shahr ki aavaaz hai

Meri aavaaz, meri nasl ki aavaaz hai

Meri aavaaz ki baazgasht nasl dar nasl chale gi…’

(My voice, is the voice of my city

My voice, is the voice of my generation

The echo of my voice will continue from generation to generation…’)

Further she writes in this poem:

‘Main payambar nahi hoon

Main toa bas aaj ko aankhen khol kar dekh rahi hoon.’

(I am not a prophet

I am just watching today by opening my eyes)

Kishwar Aapa has narrated these conditions seen with open eyes in her poetry. Alongwith the continuous narrative of individualistic experience, her poetry can also be read as a bitter and harsh comment on the present period; where the incident of this era becomes poetry after being molded into personal experience. The poetry of Kishwar Naheed achieves it distinction from the illustration of this very couple of facets of experience, the individualistic and the collective. After reading Kishwar aapa’s poems from the 1960s, one could say with confidence that Urdu poetry became able enough to endure a woman.

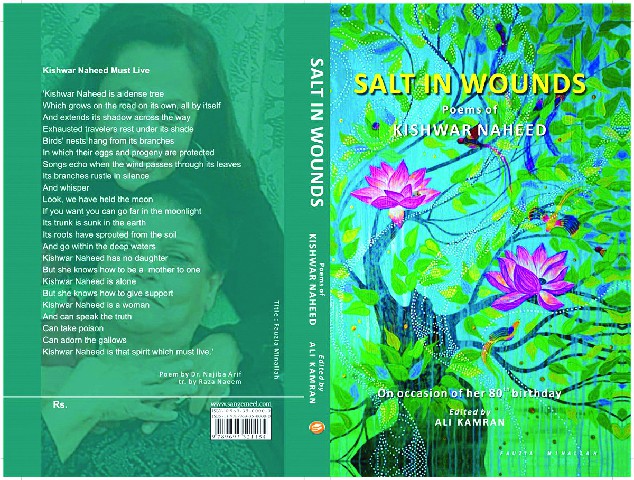

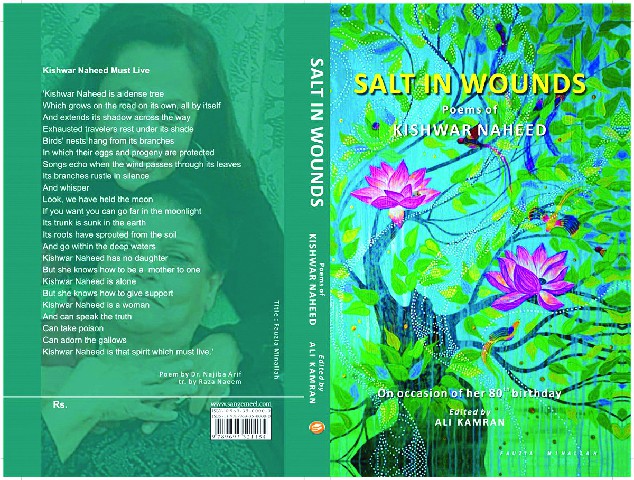

There are 3 poems which are all recent that I would like to mention here. Incidentally I have also translated all three. One is a poem not written by her, but about her Kishwar Naheed Ko Zinda Rehna Chahiye (Kishwar Naheed Must Live), written by Dr Najiba Arif, which is also on the back cover of the special anniversary volume commissioned for her 80th birthday last year. Then there is a long poem on COVID – 19 in early 2020 titled Kon Inka Maseeha Banega (Who Will Be Their Messiah) which is probably the first poem she wrote on the pandemic and I had the honour to translate it; I had the honour to recite the translated poem at an online talk I was invited to give last year on the ramifications of COVID – 19 in Pakistan at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, one of Russia’s most prestigious universities. The third one is very special because when the unfortunate George Floyd was murdered in Minnesota in May last year, I rang Kishwar Aapa up and insisted that there must be a poem on this. So she wrote the poem George Floyd – Mein Amar Ho Gaya (George Floyd – I Became Immortal) on the tragedy and then amended it later. She later told the late Asif Farrukhi that this is Raza’s poem; he wrung it out of me. This will always be a source of great pride and honour for me!

Note: All translations are by Raza Naeem. Interview courtesy ‘Bulandshahr Legacy’ (https://bulandshahrlegacy.org)

- Why is Kishwar Naheed referred to as ‘Aapa’?

Aapa is a fond honorific used across South Asia (especially in the Urdu-speaking community) to denote that someone is like an elder sister in terms of her age and experience. We regard Kishwar Naheed as Aapa because she is the patron saint of not only all women in Pakistan but also the feminist movement across South Asia!

- Kishwar Naheed’s work, engrossed for decades, people appreciate it for generations. What makes her work so relevant?

Her work is relevant because it not only reflects her own personal journey as a poet and feminist but rather more than autobiography – as I have also argued in my piece on her in The Wire which you cited – it is the voice of a whole generation which came of age in the 1960s (both during the dictatorship of Ayub Khan in Pakistan and broader currents of resistance across the Third World). In her poetry, Naheed has universalized her Pakistani identity by striving to gather together the sorrows and travails of all the women of the Third World. That is why her work is read and translated from Delhi to Buenos Aires.

- In her work, she usually presents herself (and other women) as a ‘Bad Woman’ or ‘sinful woman’. How does this characterisation reflect on South Asian gender dynamics?

Yes it is true that Kishwar Naheed was the first truly bad woman or sinful woman of Urdu poetry. But in Urdu prose her predecessors were the communist doctor Rashid Jahan (who died early) and the fearsome writer Ismat Chughtai, who was hauled before a British Indian court for addressing the theme of homosexuality in one of her stories. More recently, Naheed has had counterparts of the bad woman across other cultures and continents. One thinks of Simone de Beauvoir (whose book The Second Sex Naheed published in an abridged translation), Nawal El Saadawi (who passed away earlier this year) and the likes of Germaine Greer, Eve Ensler and Betty Friedan, etc. In terms of South Asian gender dynamics, the bad woman represents how many girls of the middle-class in traditional households were restricted, and women like Kishwar Naheed had to fight for the basic right to study further. This struggle was later reflected in various stages of freedom and expression which Naheed negotiated successfully. Naheed’s struggle gave way to other successful ‘bad women’ in Urdu poetry like Fahmida Riaz and Sara Shagufta. Today the term ‘bad woman’ has taken on a different meaning in South Asia because we are theoretically living in a modern age, but women’s rights across South Asia are being rolled back by patriarchy and conservatism. Take the case of the Aurat March in Pakistan, which has been held successfully across our major cities despite overt and covert threats, intimidation and court cases being instituted against them. The term ‘bad woman’ has become the new normal for young women in South Asia, who had taken for granted the very rights women like Kishwar Naheed had fought for. Even these rights are now being rolled back in the 21st century. But the bad women are mutiplying!

“The term ‘bad woman’ thus denotes the modern woman whose biggest crime is her intelligence”

Naheed had once referenced the French poet Saint-John Perse saying: ‘My story is the story of that street woman who recites the fatiha amid sorrow, bites the wayfarers, proceeds with the prince or the dagger held in her arms.’

The term ‘bad woman’ thus denotes the modern woman whose biggest crime is her intelligence.

- Tell us a bit about your work on the sketch of Kishwar Naheed.

Oh that came about last year on Kishwar Naheed’s 80th birthday. I wanted to write a personalized tribute to her. But having already written two essays on her and being a contributor to a book of her translated poems released on her 80th birthday, I wanted to do something different. So I came across the radical Pakistani writer Ahmad Bashir’s long incendiary sketch of her which was published when she was in her 40s, just before the early death of her husband, and just starting to become notorious. It is a no-holds-barred sketch of the poet and it became so notorious that its repute spread from Lahore to London, as soon as Bashir had read it in the presence of the poet herself and her husband and Intizar Hussain wrote about it in his column. Everyone wanted to have a copy of it.

So in 2020, on Naheed’s 80th birthday, I wanted the younger generation to get to know her better, so I thought the sketch fulfils that purpose. It has been published in The Friday Times in four installments.

My only regret is that it has yet to be published in India. But I tremendously enjoyed translating it!

- Recognised as an eminent feminist Urdu-Poet, Kishwar Naheed discusses a lot about the man-woman relationship. What other issues does her work highlight?

Well yes, any woman poet is immediately expected and stereotyped to produce poetry related to man-woman relationships or exclusively women’s issues. Many excellent Urdu poets have achieved this to perfection like Parveen Shakir, Ada Jafri and Zehra Nigah (who is still living and active); among contemporary poets you have Ishrat Afreen, Tanvir Anjum, Yasmeen Hameed, Ambreen Salahuddin, Fatema Hasan, Shahida Hasan and Azra Abbas, but Naheed has also written about other issues and continues to write about them. The circle of her poetry has been getting wider since a long time ago. Other issues she has explored in her poetry are her marital life, employment, the creation and destruction of united Pakistan, the political and social landscape and feminine sensibility, as well as some of the cardinal events of our time like the Chinese Revolution, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and 9/11. More recently, she has addressed the Donald Trump phenomenon as well as the murder of the African-American George Floyd in Minnesota last year; the growing Talibanization and Saffronization of Pakistani and Indian societies respectively; and built up a significant body of work on the COVID – 19 pandemic and its local and global ramifications. I believe that Kishwar Aapa is the most prolific and varied Urdu poet of our time!

- She has witnessed both the partitions – British India (1947) and Bangladesh (1971). Do you see any correspondence to such experience in her work?

Not really! Yes she did witness the depredations of partition as a 7-year old girl of a conservative middle-class family uprooted from her native Bulandshahr, but she quickly assimilated within the Pakistani Punjabi culture upon migration to Lahore. So partition itself does find a mention in her celebrated memoir Buri Aurat Ki Katha but it does not affect her work per se like it did her distinguished contemporaries like Intizar Hussain (also a fellow Bulandshahri), Abdullah Hussein or Quratulain Hyder. who are known for addressing such themes in their most important works. I mean Naheed is not known for her poems on partition; she hasn’t written any!

In the case of 1971, there are just a couple of chapters in her memoirs but no poetry. She has herself told me that there was a news blockade imposed by the Pakistani military dictatorship on any news coming from East Pakistan and so even when she accompanied a delegation of Pakistanis on a fact-finding mission to Dhaka at the height of the bloodbath there, she fled in horror from the carnage on a plane. So again she hasn’t really addressed this second partition in her poetry as well.

“I think Kishwar Naheed is really lucky that she is one of the most translated Urdu poets of the 20th century, if not the most translated. As far as I know, she has been translated into most of the great languages”

- How has her work influenced the field of history?

I would say it has to a certain extent, and more directly in the context of her poems from the dictatorship period of the Zia-ul-Haq regime, Pakistan’s worst military regime. Read any of her poems from that period from 1981 to 1986 and you will understand what I am talking about. Let me give the reference of just one of her poems, Mein Kaun Hoon (‘Who Am I?’), in which the echo of a whole movement can be heard which especially in the regime of Zia-ul-Haq had spread like a wave of consciousness in reaction to the trampling of women’s rights.

- How has translation helped her work reach a larger audience while not losing the ethos of the author?

I think Kishwar Naheed is really lucky that she is one of the most translated Urdu poets of the 20th century, if not the most translated. As far as I know, she has been translated into most of the great languages, including for the United Nations. I can only speak for the quality of her English translations, which have been appearing regularly since 1972. They are of varying quality as is usually the case, but they have helped establish her as the representative voice of Pakistani feminism, much like you would say about Simone de Beauvoir and Nawal El Saadawi. I mean to me she is Pakistani feminism! The writer herself is actually not very satisfied with the quality of her work in translation. In my own humble translations of her work, I have consciously tried to bring out her daring political and feminist concerns, but I also believe in maintaining a certain jauntiness of ryhme.

- According to you, what makes Kishwar Naheed’s work distinct from others?

Kishwar Naheed is identified as a distinct voice in modern Urdu poetry. Her tone is individualistic but it has the echo of the widest collective experience:

‘Meri aavaaz, mere shahr ki aavaaz hai

Meri aavaaz, meri nasl ki aavaaz hai

Meri aavaaz ki baazgasht nasl dar nasl chale gi…’

(My voice, is the voice of my city

My voice, is the voice of my generation

The echo of my voice will continue from generation to generation…’)

Further she writes in this poem:

‘Main payambar nahi hoon

Main toa bas aaj ko aankhen khol kar dekh rahi hoon.’

(I am not a prophet

I am just watching today by opening my eyes)

Kishwar Aapa has narrated these conditions seen with open eyes in her poetry. Alongwith the continuous narrative of individualistic experience, her poetry can also be read as a bitter and harsh comment on the present period; where the incident of this era becomes poetry after being molded into personal experience. The poetry of Kishwar Naheed achieves it distinction from the illustration of this very couple of facets of experience, the individualistic and the collective. After reading Kishwar aapa’s poems from the 1960s, one could say with confidence that Urdu poetry became able enough to endure a woman.

- What is your favourite work of Kishwar Naheed?

There are 3 poems which are all recent that I would like to mention here. Incidentally I have also translated all three. One is a poem not written by her, but about her Kishwar Naheed Ko Zinda Rehna Chahiye (Kishwar Naheed Must Live), written by Dr Najiba Arif, which is also on the back cover of the special anniversary volume commissioned for her 80th birthday last year. Then there is a long poem on COVID – 19 in early 2020 titled Kon Inka Maseeha Banega (Who Will Be Their Messiah) which is probably the first poem she wrote on the pandemic and I had the honour to translate it; I had the honour to recite the translated poem at an online talk I was invited to give last year on the ramifications of COVID – 19 in Pakistan at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, one of Russia’s most prestigious universities. The third one is very special because when the unfortunate George Floyd was murdered in Minnesota in May last year, I rang Kishwar Aapa up and insisted that there must be a poem on this. So she wrote the poem George Floyd – Mein Amar Ho Gaya (George Floyd – I Became Immortal) on the tragedy and then amended it later. She later told the late Asif Farrukhi that this is Raza’s poem; he wrung it out of me. This will always be a source of great pride and honour for me!

Note: All translations are by Raza Naeem. Interview courtesy ‘Bulandshahr Legacy’ (https://bulandshahrlegacy.org)