The name’s spelled Dr Ishrat Ul Ebad Khan but Karachi’s press has, over a decade, given it a many-mangled splendour with hyphens and phonetic interpretations: Ishrat-ul-Ibad, Ishratul Ibad, Ishrat ul Ibad… “Islamabad bhi likh dete hain,” he says with a laugh on the phone from Dubai. They’ve even called him Islamabad by mistake. The irony is not lost on him—he did, after all, represent the federal government in Sindh.

Dr Ishrat Ul Ebad Khan—capital U and E—is no longer the governor of Sindh, having been replaced by Justice (r) Saeeduzzaman Siddiqui in the first week of November. He stepped down after 14 years on the job, which makes him the longest serving governor to date, a feat which attracts derision and admiration in equal measure. Only a politician’s politician could have outlasted three presidents, three chiefs of army staff and eight prime ministers, not to mention five chief ministers and four spy chiefs. “I worked day and night and turned those 14 years into the equivalent of 25,” he says. One does not doubt that it was a demanding post—but it also came with great power and privilege and the capacity to do something for Karachi and Sindh. And while it may not be fair to judge a man based on how he exits a position, it is a fact that Dr Ishrat Ul Ebad was asked to resign and he swiftly left the country.

The road to Governor House

Ishrat Ul Ebad Khan was born on March 2, 1963 in Karachi. His father’s family home was in North Nazimabad’s Block D and they later moved to Block N. He has one sister and six brothers. (One brother has since passed away.) His elder brother is also a doctor.

Ishrat’s early education took place at AUISS school in the neighbourhood. Inspired by his brother, he eventually headed into medicine and went to Dow Medical College. “There were three or four of us friends,” he recalls. “We weren’t political at all. We were the nerdy kind.” They were so studious that no girl would have anything to do with them. He likes to joke about it.

It was at medical college that Ishrat joined the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organisation (APMSO). He likens it now to being swept up in a “tide”. Part of the motivation to join came from the desire to “rectify” wrongs on campus, as he puts it. “Sometimes there were fights,” he says. “You’d enter college and there would be an atmosphere of silence, anxiety—hoo ka alam.” There was a lot of misbehaviour with the professors, who Ishrat regarded as fatherly figures. “They would often say, ‘Come home after clinic’, if I needed something explained.” He found the “badtameezi” unacceptable. Were the professors generally Urdu-speaking? No, he clarifies, there were Sindhi-speaking as well as others. It was not an ethno-linguistic matter.

To young men like him, the APMSO was the platform to correct this and stand up to the “powerful” people even though they were just students. Ishrat Ul Ebad says they went about trying to achieve three things: end the mistreatment of teachers, ensure that the five-year programme completed on schedule, and clean up the hospital environment. The “hungamas”, fighting on campus and turbulence meant that the students were taking up to seven years to graduate with an MBBS, which affected their further studies abroad. “We brought it down to five and a half years,” he says.

He and other young men like him also found that the APMSO helped counter a right-wing party’s student wing on campus. Students like him were irritated when the more orthodox students fought with them over playing music at concerts on campus. It was in these interactions that a young Ishrat began to display political talents that would stand him in good stead as governor.

The recruiters of new blood for the APMSO had sussed him out in the initial days. He was eloquent when it came to giving orientations, hosting programs and giving speeches. He was a wonderful negotiator whenever they needed to acquire permission from the administration to hold an event. He was their man when they clashed with the right-wing students. Once there was a face-off over holding a concert. “They said not during college, so we said, alright, not during college time. Then they said, point janay ke baad,” he recalls. They were happy to compromise but they would not back down. He won first prize for playing the guitar at the concert. It was the instrumental theme for the song ‘Where do I begin’ by Francis Lai from Erich Segal’s ‘Love Story’.

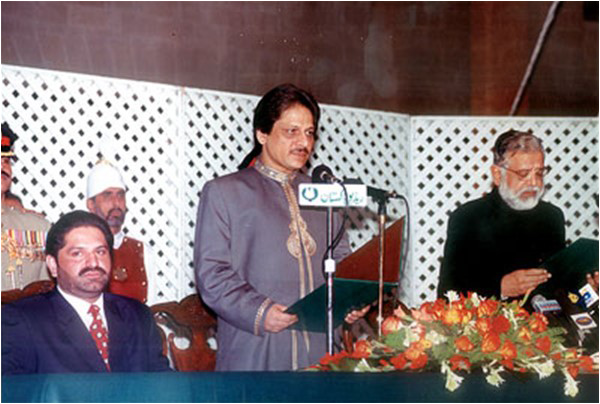

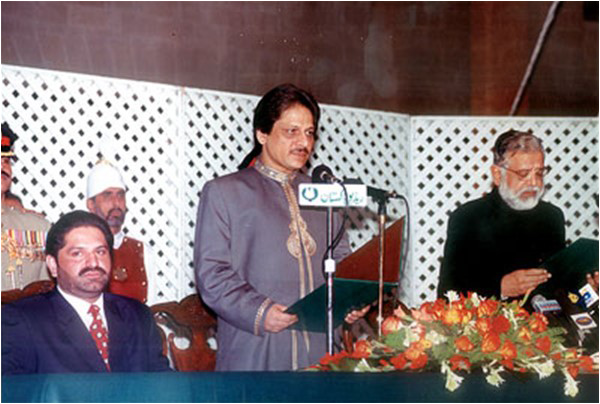

Dr Ishrat completed his house job in April 1990. He had also been growing politically and was in the good books of Altaf Hussain and Imran Farooq. Recognition within the party and outside had already begun. He went to study in the UK where his brother lived. But upon his return to take his family back, he ended up staying as the 1990 elections happened. He was awarded a ticket by the party to contest the polls and he won, unsurprisingly. He was given the portfolio for housing and town planning.

In 1993, however, he left for London and Dublin and says he picked up on medicine and surgery. It was only in December 2002 that he came back, after his name was given for governor. According to one version of events, Altaf Hussain was asked to give three names for the slot. He gave his own, his tiny daughter Afza’s and Ishrat Ul Ebad’s. In effect, there was only one choice then.

Governor ‘rule’

When Ebad arrived from London in 2002, ascerbic but astute Dawn columnist, the late Ardeshir Cowasjee, called him an “imported” governor. Others described him as being “installed”. “He was not a governor; he was a middle-man, a negotiator brought into the arena by Pervez Musharraf and Altaf Hussain for their own interests,” remarks a notable personality of the city and a former top office bearer, who preferred not to be named. But in all fairness, this was no different a method of appointment for the key posts in the province as the examples of the chief ministers and inspectors general of police have proven. And so, for better or worse, Ebad came to be known as the Establishment’s man even though most people acknowledged that his methods were non-Establishment.

It was Ishrat Ul Ebad’s fate to oversee a city that was at war with itself. His career as governor spanned three distinct eras. From 2003 to 2008 it was one under Musharraf with one form of government. In 2008, the elections changed the political dispensation and Asif Zardari came to the scene. From 2013 onward it was Nawaz Sharif’s government.

All this time, being governor was not easy and he feels he was tested each day. “It was like in the morning it was one [exam] paper, with difficult questions and no choices,” he says. “In the afternoon it was another paper. At night another.” He considers aiming for the stability of Karachi the greatest challenge he faced. He would sit quietly at the apex committee meeting on law and order set up to end the bloodshed in Karachi. Presentations would be made, statistics of success would be presented. He says he would listen and then dismiss the numbers: “Figure-shigur nahi dekhaya karo. How do you think you can make this sustainable?” he would ask. He knew one thing about the Karachi operation: They were pushing this weighty thing up a steep 45-degree slope. If they did not manage to get it to the top, it would fall back on them with double the force.

Few will dispute that he worked the back channels for his former party, the MQM, and others in a manner which suited everybody. He was an opener placed in the middle order, because the captain believed that he would save the game when the top order fell. Former comrades grudgingly nod to this. For example, last year he pressed the PTI and MQM to meet at Governor House to kiss and make up after a clash at Azizabad. When blood was shed in Karachi in 2008, he set up a peace committee and worked on party grievances. The ANP, PPP and MQM all needed handling. Sometimes he was successful, sometimes not. The subsequent years saw incredible amounts of bloodshed and it was only until the Karachi operation was launched in 2013 by the Rangers and other law-enforcement arms that some progress was made.

These were also the years when extortion, target killing and sectarian violence plagued the city. Indeed, Ebad’s first act in office was to promulgate on December 28, 2002, an ordinance: ‘The Sindh Eradication and Curbing the Menace of Involuntary Donation or Forced Chanda Ordinance 2002.’ One wonders if he could have done more over the years to have leveraged his office to control the city. When he came to power, one of the first things he promised was the end the rural-urban divide, but one can question if he succeeded in accomplishing this in his capacity.

He counts as his successes his work towards development of Sindh, which required prodding the federal and provincial governments. He says he successfully negotiated the Tameer-e-Karachi programme in 2003, restarted the work on the Lyari Expressway and KIV water supply project. He worked on the prime minister to provide finding for the mass transit Green Line, among other projects. But perhaps the accompishment he is most proud of is the Dow University Ojha Campus which now does liver transplants and plans on soft tissue ones next. He feels happy to say that when he joined office, Sindh had 19 universities and now it has more than 50.

A more forgiving view would be to see that the governor perhaps prevented Karachi’s volatile political scene from turning into an inferno. Without a doubt, he worked to calm tempers and bring people to the negotiation table. The formula was simple and effective: let them drain themselves of all their vitriol and then he would speak. At some point they would cave in. He knew the art of making people feel important. He would encourage politicians, especially those who were hot under the collar, to call him before they shot off their mouths. Once he gave advice to one particularly vocal figure (who had been rather public about his feelings for the PPP even though he had once been close to its chief): Get bhabi to make you dhania ka paani, advised Ebad, take a cold shower and go to sleep, respond to the problem in the morning. Another politician from a party that enjoyed a brief rise and fall in Karachi would call him distraught or angry. “Carburator me phir kuch phans gaya he kya,” he would ask. He knew how to talk them back from the ledge.

Those were difficult times in Karachi and perhaps even the best of politicians would have been tested sorely. “In order to understand Karachi think of a pizza box,” he says. “It’s square. You open it, it’s round. By the time you are done with it, it’s a cone. If you try to make a decision when it’s a square, then you’ll have trouble.”

And so, the bended knee, the olive branch and the silver tongue worked well. “There was so much bitterness,” Ebad says. “I would talk to people. Jhook ke mila logon se. I’d make the chotas bara.” This can be seen as an oblique reference to Karachi Mayor Mustafa Kamal.

In fact, just days before he was asked to resign a particular ugly episode erupted with the former mayor. Mustafa Kamal decided to unleash a stream of vitriol in the governor’s direction. He levelled allegations and made accusations. The governor issued an official rebuttal, but then, perhaps for the first time, he did not hold back. He said what he wanted to say on television. It was ugly. For Ebad a red line had been crossed. The accusations were seen as just a symptom of the Pak Sarzameen Party’s growing desperation. Karachi was not the same. The Muttahida Qaumi Movement was not the same. Everything had changed.

What lies ahead

For now, Ebad, a British national, is headed to London. His family appears to be well settled. (His elder daughter is a neurosurgeon, doing her PhD. One son is a doctor and the other has studied medical engineering. And one daughter has studied art and 3D animation. He credits his wife Shaheena for pushing them ahead. “Wo adhi doctor ban gai hain. Adhi artist,” he quips.) These days she is packing up before joining him in Dubai and heading to London. He plans to stay there for a bit. But he will be back. Men like him don’t stay on the sidelines for long.

The writer is a journalist working with an English daily

Dr Ishrat Ul Ebad Khan—capital U and E—is no longer the governor of Sindh, having been replaced by Justice (r) Saeeduzzaman Siddiqui in the first week of November. He stepped down after 14 years on the job, which makes him the longest serving governor to date, a feat which attracts derision and admiration in equal measure. Only a politician’s politician could have outlasted three presidents, three chiefs of army staff and eight prime ministers, not to mention five chief ministers and four spy chiefs. “I worked day and night and turned those 14 years into the equivalent of 25,” he says. One does not doubt that it was a demanding post—but it also came with great power and privilege and the capacity to do something for Karachi and Sindh. And while it may not be fair to judge a man based on how he exits a position, it is a fact that Dr Ishrat Ul Ebad was asked to resign and he swiftly left the country.

The road to Governor House

Ishrat Ul Ebad Khan was born on March 2, 1963 in Karachi. His father’s family home was in North Nazimabad’s Block D and they later moved to Block N. He has one sister and six brothers. (One brother has since passed away.) His elder brother is also a doctor.

Ishrat’s early education took place at AUISS school in the neighbourhood. Inspired by his brother, he eventually headed into medicine and went to Dow Medical College. “There were three or four of us friends,” he recalls. “We weren’t political at all. We were the nerdy kind.” They were so studious that no girl would have anything to do with them. He likes to joke about it.

It was at medical college that Ishrat joined the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organisation (APMSO). He likens it now to being swept up in a “tide”. Part of the motivation to join came from the desire to “rectify” wrongs on campus, as he puts it. “Sometimes there were fights,” he says. “You’d enter college and there would be an atmosphere of silence, anxiety—hoo ka alam.” There was a lot of misbehaviour with the professors, who Ishrat regarded as fatherly figures. “They would often say, ‘Come home after clinic’, if I needed something explained.” He found the “badtameezi” unacceptable. Were the professors generally Urdu-speaking? No, he clarifies, there were Sindhi-speaking as well as others. It was not an ethno-linguistic matter.

Only a politician's politician could have outlasted three presidents, three chiefs of army staff and eight prime ministers, not to mention five chief ministers and four spy chiefs. "I worked day and night and turned those 14 years into the equivalent of 25," he says

To young men like him, the APMSO was the platform to correct this and stand up to the “powerful” people even though they were just students. Ishrat Ul Ebad says they went about trying to achieve three things: end the mistreatment of teachers, ensure that the five-year programme completed on schedule, and clean up the hospital environment. The “hungamas”, fighting on campus and turbulence meant that the students were taking up to seven years to graduate with an MBBS, which affected their further studies abroad. “We brought it down to five and a half years,” he says.

He and other young men like him also found that the APMSO helped counter a right-wing party’s student wing on campus. Students like him were irritated when the more orthodox students fought with them over playing music at concerts on campus. It was in these interactions that a young Ishrat began to display political talents that would stand him in good stead as governor.

The recruiters of new blood for the APMSO had sussed him out in the initial days. He was eloquent when it came to giving orientations, hosting programs and giving speeches. He was a wonderful negotiator whenever they needed to acquire permission from the administration to hold an event. He was their man when they clashed with the right-wing students. Once there was a face-off over holding a concert. “They said not during college, so we said, alright, not during college time. Then they said, point janay ke baad,” he recalls. They were happy to compromise but they would not back down. He won first prize for playing the guitar at the concert. It was the instrumental theme for the song ‘Where do I begin’ by Francis Lai from Erich Segal’s ‘Love Story’.

Dr Ishrat completed his house job in April 1990. He had also been growing politically and was in the good books of Altaf Hussain and Imran Farooq. Recognition within the party and outside had already begun. He went to study in the UK where his brother lived. But upon his return to take his family back, he ended up staying as the 1990 elections happened. He was awarded a ticket by the party to contest the polls and he won, unsurprisingly. He was given the portfolio for housing and town planning.

In 1993, however, he left for London and Dublin and says he picked up on medicine and surgery. It was only in December 2002 that he came back, after his name was given for governor. According to one version of events, Altaf Hussain was asked to give three names for the slot. He gave his own, his tiny daughter Afza’s and Ishrat Ul Ebad’s. In effect, there was only one choice then.

Governor ‘rule’

When Ebad arrived from London in 2002, ascerbic but astute Dawn columnist, the late Ardeshir Cowasjee, called him an “imported” governor. Others described him as being “installed”. “He was not a governor; he was a middle-man, a negotiator brought into the arena by Pervez Musharraf and Altaf Hussain for their own interests,” remarks a notable personality of the city and a former top office bearer, who preferred not to be named. But in all fairness, this was no different a method of appointment for the key posts in the province as the examples of the chief ministers and inspectors general of police have proven. And so, for better or worse, Ebad came to be known as the Establishment’s man even though most people acknowledged that his methods were non-Establishment.

It was Ishrat Ul Ebad’s fate to oversee a city that was at war with itself. His career as governor spanned three distinct eras. From 2003 to 2008 it was one under Musharraf with one form of government. In 2008, the elections changed the political dispensation and Asif Zardari came to the scene. From 2013 onward it was Nawaz Sharif’s government.

All this time, being governor was not easy and he feels he was tested each day. “It was like in the morning it was one [exam] paper, with difficult questions and no choices,” he says. “In the afternoon it was another paper. At night another.” He considers aiming for the stability of Karachi the greatest challenge he faced. He would sit quietly at the apex committee meeting on law and order set up to end the bloodshed in Karachi. Presentations would be made, statistics of success would be presented. He says he would listen and then dismiss the numbers: “Figure-shigur nahi dekhaya karo. How do you think you can make this sustainable?” he would ask. He knew one thing about the Karachi operation: They were pushing this weighty thing up a steep 45-degree slope. If they did not manage to get it to the top, it would fall back on them with double the force.

Few will dispute that he worked the back channels for his former party, the MQM, and others in a manner which suited everybody. He was an opener placed in the middle order, because the captain believed that he would save the game when the top order fell. Former comrades grudgingly nod to this. For example, last year he pressed the PTI and MQM to meet at Governor House to kiss and make up after a clash at Azizabad. When blood was shed in Karachi in 2008, he set up a peace committee and worked on party grievances. The ANP, PPP and MQM all needed handling. Sometimes he was successful, sometimes not. The subsequent years saw incredible amounts of bloodshed and it was only until the Karachi operation was launched in 2013 by the Rangers and other law-enforcement arms that some progress was made.

These were also the years when extortion, target killing and sectarian violence plagued the city. Indeed, Ebad’s first act in office was to promulgate on December 28, 2002, an ordinance: ‘The Sindh Eradication and Curbing the Menace of Involuntary Donation or Forced Chanda Ordinance 2002.’ One wonders if he could have done more over the years to have leveraged his office to control the city. When he came to power, one of the first things he promised was the end the rural-urban divide, but one can question if he succeeded in accomplishing this in his capacity.

He counts as his successes his work towards development of Sindh, which required prodding the federal and provincial governments. He says he successfully negotiated the Tameer-e-Karachi programme in 2003, restarted the work on the Lyari Expressway and KIV water supply project. He worked on the prime minister to provide finding for the mass transit Green Line, among other projects. But perhaps the accompishment he is most proud of is the Dow University Ojha Campus which now does liver transplants and plans on soft tissue ones next. He feels happy to say that when he joined office, Sindh had 19 universities and now it has more than 50.

A more forgiving view would be to see that the governor perhaps prevented Karachi’s volatile political scene from turning into an inferno. Without a doubt, he worked to calm tempers and bring people to the negotiation table. The formula was simple and effective: let them drain themselves of all their vitriol and then he would speak. At some point they would cave in. He knew the art of making people feel important. He would encourage politicians, especially those who were hot under the collar, to call him before they shot off their mouths. Once he gave advice to one particularly vocal figure (who had been rather public about his feelings for the PPP even though he had once been close to its chief): Get bhabi to make you dhania ka paani, advised Ebad, take a cold shower and go to sleep, respond to the problem in the morning. Another politician from a party that enjoyed a brief rise and fall in Karachi would call him distraught or angry. “Carburator me phir kuch phans gaya he kya,” he would ask. He knew how to talk them back from the ledge.

Those were difficult times in Karachi and perhaps even the best of politicians would have been tested sorely. “In order to understand Karachi think of a pizza box,” he says. “It’s square. You open it, it’s round. By the time you are done with it, it’s a cone. If you try to make a decision when it’s a square, then you’ll have trouble.”

And so, the bended knee, the olive branch and the silver tongue worked well. “There was so much bitterness,” Ebad says. “I would talk to people. Jhook ke mila logon se. I’d make the chotas bara.” This can be seen as an oblique reference to Karachi Mayor Mustafa Kamal.

In fact, just days before he was asked to resign a particular ugly episode erupted with the former mayor. Mustafa Kamal decided to unleash a stream of vitriol in the governor’s direction. He levelled allegations and made accusations. The governor issued an official rebuttal, but then, perhaps for the first time, he did not hold back. He said what he wanted to say on television. It was ugly. For Ebad a red line had been crossed. The accusations were seen as just a symptom of the Pak Sarzameen Party’s growing desperation. Karachi was not the same. The Muttahida Qaumi Movement was not the same. Everything had changed.

What lies ahead

For now, Ebad, a British national, is headed to London. His family appears to be well settled. (His elder daughter is a neurosurgeon, doing her PhD. One son is a doctor and the other has studied medical engineering. And one daughter has studied art and 3D animation. He credits his wife Shaheena for pushing them ahead. “Wo adhi doctor ban gai hain. Adhi artist,” he quips.) These days she is packing up before joining him in Dubai and heading to London. He plans to stay there for a bit. But he will be back. Men like him don’t stay on the sidelines for long.

The writer is a journalist working with an English daily