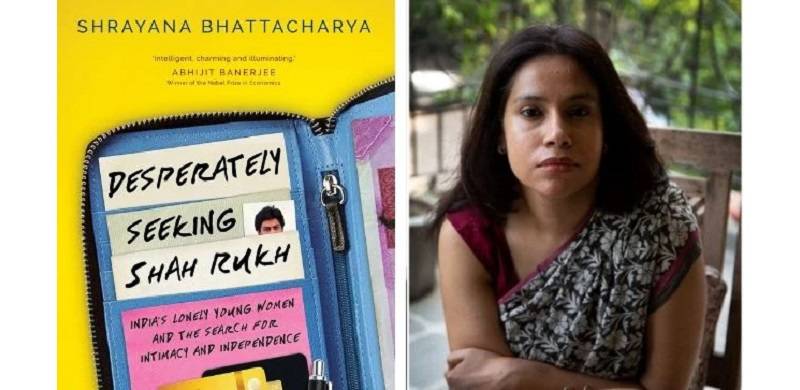

Shrayana Bhattacharya is trained in development economics at Delhi University and Harvard University. Since 2014, in her role as an economist at a multilateral development bank, she takes keen interest in documenting issues focused on social policy and jobs. Prior to joining the World Bank, she has worked with ISST, ILO, SEWA and Centre for Policy Research on a range of issues in the areas of urban bureaucracy, social protection and informality. She completed her post-graduation in public administration and economics.

In this trailblazing work, Bhattacharya draws the economic and individual flights, the jobs, desires, prayers, love affairs and rivalries, of a varied group of women. Divided by class but united in fandom, they remain persistent in their search for intimacy, independence and fun. Embracing the universal film idol Shah Rukh Khan allows them a small respite from an oppressive culture, a boost to their fantasies of friendlier masculinity in men. Khan is a unifying factor for women, Adivasi and Brahmin. The author, an accomplished economist and writer, chose Khan as the constant for her study of Indian women, and to an extent men, born in the 1980s and ’90s. Most of the women struggle to find the freedom – or income – to follow their favourite actor. Using his films and the reforms of 1991 as starting points, the author makes women talk about their lives, from compromises to outright rebellion, despite being educated and upwardly mobile. The magical SRK touch adds to the readability and fun factor of the book. But there is no magic bullet to empowerment.

For example, Baazigar confronts the changes in the nature of relations within families and the societal convention during this economic boom. It also emphasises the nature of resistance for women in tier-two cities, away from the cosmopolitan milieu of the big cities. The stories of women in this section all involve the baazis, or gambles, that women in tier-II cities take, in order to live a life they dream of. The stories ‘The Accountant’ and ‘A Girl called Gold’ feature the struggle and conflict at home to gain an education, choose a career and resist the pressures to “settle down.” While Gold makes the ultimate gamble and runs away from her Rajasthan home, ‘The Accountant’ grapples with the resistance within the confines of her home, revealing the many shades of pushback against restrictive traditional family structures.

In ‘Working from Home,’ the author leaves the capital and travels to Gujarat, Jharkhand and the Northeast. She provides insights into the invisible lives of women in home-based industries such as textiles and tobacco as well as domestic and field survey workers. The first destination is Ahmedabad. Given the massive socio-economic gap between the author and the women, she breaks the ice easily about their lives, love and aspirations through Shah Rukh, his movies and music! The women open up about their brawls after the author uses the question: Who is your favourite actor? With the underlying metaphor of dialogue from the movie Kuch Kuch Hota Hai — a home that is built on compromise and not love is not a home (ghar), it’s a house (makaan) – the author demonstrates the choices women of the slum struggle with for mobility and economic independence. The second story is from Rampur, UP, where Manju embodies the boredom of women in small-town India that have been denied support for work and relaxation. While young men get to ride bikes and watch movies, girls are deprived of freedom of movement for work or leisure, resulting in inequality through boredom.

Forgiven for having called it a chick-lit, I picked up the book just to relive my own fan-girl moments. But it does much more than just give a peek into the iconic status of one of India’s favourite film stars. It offers a powerful commentary on the lives of Indian women and the ways they deal with inequities. Shah Rukh Khan has been the misery of existence for a plethora of men. It’s not that women compare them to SRK when they’re dating men; it’s just that one knows in the heart that one is comparing them to their favourite Khan role. Women can’t help it. When things go south, they just know it’s his fault, and the fault of those damned expectations that he’s given them.

Most of the romantic roles played by Khan from his oeuvre of Karan Johar and Yash Chopra are in stark contrast to the heroes of the 1970s and ’80s, who were protectors and patriarchs (rather than lovers). Several characters played by Sharmila Tagore, Zeenat Aman, Parveen Babi, et al started the film wearing skirts and boozing, only for the hero to turn them into good Indian women by the end. A woman who had started the movie wearing revealing dresses would end up wearing a chaste sari. Imagine the thrill of finding out this extremely intelligent man who was ready to cater to the female audience.

Although not a Masters of Literature, with no precise purpose to literary analysis (more accomplished minds than mine can take on that task), I can safely say that I can fully endorse this work as a Pakistani woman too – it is deeply engaging, and as a reader, or at least a female, will take your minds down many paths which you did not know existed. As an analysis of the world of 30-something metropolitan professionals, regardless of gender, it’s a therapeutic read. It’s just accurate. Most importantly, it provides women a toolkit to steer through the changing backdrop of economy and the social order in their search for freedom and contentment.

In this trailblazing work, Bhattacharya draws the economic and individual flights, the jobs, desires, prayers, love affairs and rivalries, of a varied group of women. Divided by class but united in fandom, they remain persistent in their search for intimacy, independence and fun. Embracing the universal film idol Shah Rukh Khan allows them a small respite from an oppressive culture, a boost to their fantasies of friendlier masculinity in men. Khan is a unifying factor for women, Adivasi and Brahmin. The author, an accomplished economist and writer, chose Khan as the constant for her study of Indian women, and to an extent men, born in the 1980s and ’90s. Most of the women struggle to find the freedom – or income – to follow their favourite actor. Using his films and the reforms of 1991 as starting points, the author makes women talk about their lives, from compromises to outright rebellion, despite being educated and upwardly mobile. The magical SRK touch adds to the readability and fun factor of the book. But there is no magic bullet to empowerment.

For example, Baazigar confronts the changes in the nature of relations within families and the societal convention during this economic boom. It also emphasises the nature of resistance for women in tier-two cities, away from the cosmopolitan milieu of the big cities. The stories of women in this section all involve the baazis, or gambles, that women in tier-II cities take, in order to live a life they dream of. The stories ‘The Accountant’ and ‘A Girl called Gold’ feature the struggle and conflict at home to gain an education, choose a career and resist the pressures to “settle down.” While Gold makes the ultimate gamble and runs away from her Rajasthan home, ‘The Accountant’ grapples with the resistance within the confines of her home, revealing the many shades of pushback against restrictive traditional family structures.

In ‘Working from Home,’ the author leaves the capital and travels to Gujarat, Jharkhand and the Northeast. She provides insights into the invisible lives of women in home-based industries such as textiles and tobacco as well as domestic and field survey workers. The first destination is Ahmedabad. Given the massive socio-economic gap between the author and the women, she breaks the ice easily about their lives, love and aspirations through Shah Rukh, his movies and music! The women open up about their brawls after the author uses the question: Who is your favourite actor? With the underlying metaphor of dialogue from the movie Kuch Kuch Hota Hai — a home that is built on compromise and not love is not a home (ghar), it’s a house (makaan) – the author demonstrates the choices women of the slum struggle with for mobility and economic independence. The second story is from Rampur, UP, where Manju embodies the boredom of women in small-town India that have been denied support for work and relaxation. While young men get to ride bikes and watch movies, girls are deprived of freedom of movement for work or leisure, resulting in inequality through boredom.

Forgiven for having called it a chick-lit, I picked up the book just to relive my own fan-girl moments. But it does much more than just give a peek into the iconic status of one of India’s favourite film stars. It offers a powerful commentary on the lives of Indian women and the ways they deal with inequities. Shah Rukh Khan has been the misery of existence for a plethora of men. It’s not that women compare them to SRK when they’re dating men; it’s just that one knows in the heart that one is comparing them to their favourite Khan role. Women can’t help it. When things go south, they just know it’s his fault, and the fault of those damned expectations that he’s given them.

Most of the romantic roles played by Khan from his oeuvre of Karan Johar and Yash Chopra are in stark contrast to the heroes of the 1970s and ’80s, who were protectors and patriarchs (rather than lovers). Several characters played by Sharmila Tagore, Zeenat Aman, Parveen Babi, et al started the film wearing skirts and boozing, only for the hero to turn them into good Indian women by the end. A woman who had started the movie wearing revealing dresses would end up wearing a chaste sari. Imagine the thrill of finding out this extremely intelligent man who was ready to cater to the female audience.

Although not a Masters of Literature, with no precise purpose to literary analysis (more accomplished minds than mine can take on that task), I can safely say that I can fully endorse this work as a Pakistani woman too – it is deeply engaging, and as a reader, or at least a female, will take your minds down many paths which you did not know existed. As an analysis of the world of 30-something metropolitan professionals, regardless of gender, it’s a therapeutic read. It’s just accurate. Most importantly, it provides women a toolkit to steer through the changing backdrop of economy and the social order in their search for freedom and contentment.