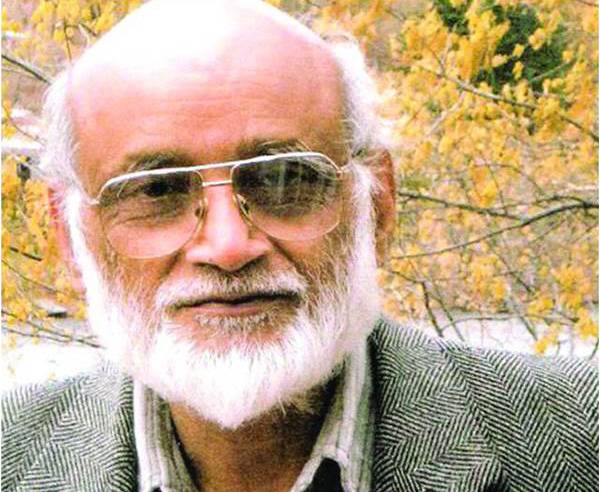

C. M. Naim,

City Press, 2013. Pp.126. ISBN: 9789698380984. Rs.350

The title of this slim volume refers to the first and longest essay in this collection of eleven pieces by the Indian-American scholar and translator Choudhri Mohammed Naim. Most of the essays are reprinted and revised editions of short articles that have appeared over the years in various publications, and which reflect, as Naim himself puts it, his “engagement with India and Indian Muslims”.

The first essay revolves around Naim’s Partition experiences, as well as those of his family. The young Naim and his friends tramped through their town, hoisting a Muslim League flag and chanting inciting slogans while tearing down Congress flags en route to school, determined to stir controversy by refusing to sing the national anthem. But once there the kindliness of a teacher, coupled with bribery consisting of an extra packet of laddu, dampened the enthusiasm of the youths, and they stood by placidly while the national anthem was sung.

The recounting of this incident is a universal reminder of the nature of much of protest. A reminder of the image of the youngster who proudly partakes in some protest march or other, only to stutter or stare blankly when quizzed about what it is he is marching for (or against). And once one has become suspicious of the authenticity of these part-time protesters, one wonders about their true motivations. Is it for the feeling of empowerment that they march through the streets, waving flags and shouting and domineering? Is it a form of release, an outlet, or just entertainment, a change from routine boredom? I wonder how many of these youths would follow the protesting practices of one of the most prominent of all 20th century Indians and refrain from eating not only laddu but anything at all.

[quote]Pakistani journalists should take note of Naim's analytical style[/quote]

Perhaps the young Naim was at heart ambivalent about Partition, for he later admits to a perpetual fluctuation of sentiment, ranging from pride at the achievement of Pakistan, to regret at the painful divisions it caused between friends and even families. His voice is an honest one, never flinching from uncertainties or complexities.

This is reflected in the remaining essays of this book, which are dominated by Naim’s deconstructions of the vitriolic and intolerant declamations by various Indian Muslim organizations and media outlets towards unorthodox groups such as the Ahmadis. This he does with a lot of skill, undermining the arguments of the opposing side by unearthing historical and religious examples of usually unquestioned authority that directly challenge the supposed Muslim orthodoxy that is being propagated by its self-appointed defenders. In short, his activity consists of picking apart prejudices, revealing fallacies, and pointing out self-contradictions as manifested in newspaper reports, websites, and other media. In addition to highlighting ignorance and hypocrisy, these tasks seem geared towards ensuring that disputes are civilized, that monolithic and oversimplified constructions of Islam and history are not allowed to prevail without opposition, and that those who would use sectarian means for political ends are exposed as being inappropriate leaders in either sphere. A relatively simple analysis of what is being said by whom and in what context is often more than enough to accomplish these goals.

[quote]An extra packet of laddus dampened the enthusiasm of the youths[/quote]

It is always instructive when a linguist takes the time and effort to illustrate the way in which language is used and abused to promulgate an agenda, hidden or otherwise. As a teacher and translator of Urdu with significant credits to his name, Naim performs his duties with diligence. It would be appropriate for Pakistani journalists and scholars to take note of the admirably analytical style of Naim and apply similar precision to their own writings and that of their contemporaries. The only flaw in this book is that it could use some editing to compensate for grammatical errors, untranslated Romanizations of Urdu words, and a somewhat jarring style in the initial sections of the first essay. These relatively minor quibbles aside, one looks forward to seeing more of Naim’s work being published in Pakistan. For instance, his annotated translation of the Zikr-i Mir, the autobiography of the 18th century poet Mir Muhammad Taqi ‘Mir’, which was published by Oxford University Press in India, should be reprinted here, it being a valuable primary source document for the Mughal period.