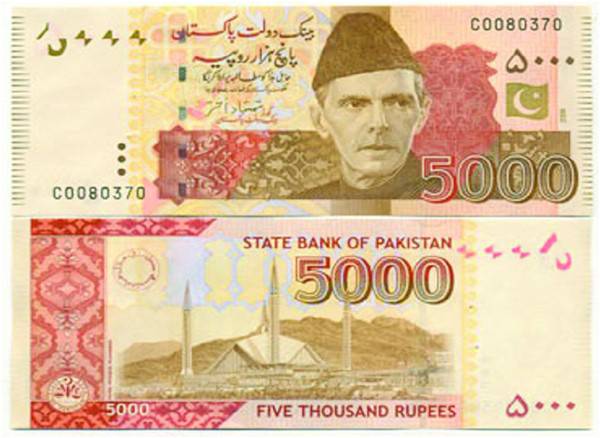

The suggestion to withdraw the Rs5,000 note is all the rage ever since the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) came to power. Enthusiastic proponents contend that discontinuing it would ameliorate corrupt practices to a large extent and save us billions.

I want to humbly argue that this suggestion lacks proper analysis of ground realities in Pakistan.

Discontinuing large currency notes is a global practice that has emerged over time. By 1969, the United States government had withdrawn the $1000 note (the largest note at present is $100), mainly to curtail its use in drug dealing and informal markets. In May 2016, the European Central Bank (ECB) banned the large denomination 500 Euro note, which had become known as ‘Bin Laden’ due to its use in terror financing, black market activities and money laundering.

In November 2016, the Indian government discontinued Rs500 and 1,000 notes overnight. This took out almost 85 percent of cash in circulation. The stated motive was to curtail black market and informal activities, corruption and tax evasion. The economic managers of Modi government felt that this would be a game changer, just like proponents in Pakistan swear to the proposed efficacy of banning the Rs5,000 note. Not to be left behind, Pakistan’s Senate passed a resolution in December 2016 to discontinue the note.

It is here that the proponents enter the zone of ‘irrational exuberance’, a term invented by the former a Federal Reserve (US’ central bank) chairman to describe unnecessary and unwarranted expectations.

Selectively pointing to India’s experiment while failing to accept that all that hassle resulted in nothing is rather unbecoming of those who are vociferously demanding the ban. Truth is that the perception, ranking and incidences of corruption remain the same or have changed little in India. What did happen was the tremendous discomfort caused to the populace, who had to stand in queues for days to exchange their banned notes for freshly issued one. Banks resorted to hoarding cash, making everyday life difficult. Those who had made their money through illegal means parked their banned money in alternative means (jewellery, property, expensive cars) and remained largely unperturbed. In carrying out this experiment, Modi’s government failed to grasp any lessons from similar experiments in India in 1946 and 1978, which also had little impact. Not to mention that curtailing the money supply shaved an estimated two percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth in India, a considerable figure given that India’s total GDP stands at more than $ 2 trillion these days.

In Pakistan, as per State Bank’s figures (August 2018 Statistical Bulletin), Pakistan’s total monetary base is Rs5.484 trillion, of which Rs4.38 trillion is currency in circulation, meaning that almost 80 percent of total money is in cash. This indicates an exceptionally high preference for cash and economic activity is heavily dependent upon it. How much of this cash is Rs5,000 notes? Nobody knows and neither is the SBP telling. In December 2016, when the Senate passed the resolution for banning the Rs5,000 note, the law minister informed that a staggering 30 percent of the total money in circulation consists of these notes. Taking the same percentage (it is highly unlikely that the percentage has changed much) as prevalent today, it would imply that Rs1.3 trillion of total cash in the economy consists of Rs5,000 notes.

Consider for a moment what would happen if all these Rs5,000 notes are banned overnight. First, the horror scenario: Rs1.3 trillion would become worthless in a day. As money supply is curtailed or disrupted, an already struggling economy will struggle further as it faces the spectre of very low growth rates. Forgers and black marketers would have a ball and economic agents (people, households and businesses) would find it difficult to get cash as hoarding ensues. Fake currency would flood the market and the rupee’s value could go down significantly, setting a bout of high inflation in process. As business activity dips, unemployment will rise as employers (especially in the informal sector) curtail their activities. If this scenario is realised, then poverty and inequality would spike further and government’s revenue will suffer as tax revenue declines.

Best case scenario? The government will print enough small denomination money to replace the Rs1.3 trillion denominated in Rs5,000. Still, people will have to queue up in front of banks for days, weeks or even months to get an equivalent amount for their Rs5,000 notes. Banks, as they usually do in times of economic stress, hoard cash. Given exceptionally high dependency upon cash transactions, the economy will take a long time to recover.

It is critically important to note an important aspect of this debate: the cost of printing money. In 2017, a SBP statement indicated incurring a cost of more than Rs9 billion to print notes of around Rs342 billion. These costs are incurred in terms of special printing machines, electricity bills for running those machines, special ink and special paper. These costs increase over time. Since large denominations lessen the cost through lesser quantity of printed money, the straightforward implication is that doing away with Rs5,000 note would increase that cost significantly. For the sake of simplicity, just take the above stated expense (Rs9 billion). If Rs342 billion incurs a printing cost of Rs9 billion, then printing Rs1.3 trillion in smaller denomination money to replace Rs5,000 would imply a cost exceeding Rs35 billion. Ultimately, these costs are recouped through the users or consumers in one way or the other. This means that people will have to ultimately bear the additional costs of printing smaller denomination notes.

The cost advantage and convenience conferred by large denomination bills is understandable when one looks at the monetary history and considers the cost of living. Increase in cost of living over time means that one has to pay more money over time for the same amount of stuff. Pakistan is no exception to this reality. Suppose now that decision makers had decided long ago, in the days of half anna and 1 rupee, that no bigger denomination than Rs1 will be printed. In 2018, this would mean that buying a car worth Rs20 lakh or more would need truckloads of cash to be delivered to the dealer or seller. Just imagine the hassle, bother and trouble one would have to go through to make that arrangement. It is exactly to avoid these kinds of hassles that large denomination notes come into existence over time, be it the Rs500 (1986), Rs1,000 (1987) or Rs 5,000 (2006).

Am I suggesting that banning the Rs5,000 note is a bad idea? No, not at all. I am simply asking a simple question: do we as a society understand the implications, costs and benefits of such a decision?

The writer is an economist and can be reached on Twitter @ShahidMohmand79

I want to humbly argue that this suggestion lacks proper analysis of ground realities in Pakistan.

Discontinuing large currency notes is a global practice that has emerged over time. By 1969, the United States government had withdrawn the $1000 note (the largest note at present is $100), mainly to curtail its use in drug dealing and informal markets. In May 2016, the European Central Bank (ECB) banned the large denomination 500 Euro note, which had become known as ‘Bin Laden’ due to its use in terror financing, black market activities and money laundering.

In November 2016, the Indian government discontinued Rs500 and 1,000 notes overnight. This took out almost 85 percent of cash in circulation. The stated motive was to curtail black market and informal activities, corruption and tax evasion. The economic managers of Modi government felt that this would be a game changer, just like proponents in Pakistan swear to the proposed efficacy of banning the Rs5,000 note. Not to be left behind, Pakistan’s Senate passed a resolution in December 2016 to discontinue the note.

It is here that the proponents enter the zone of ‘irrational exuberance’, a term invented by the former a Federal Reserve (US’ central bank) chairman to describe unnecessary and unwarranted expectations.

Selectively pointing to India’s experiment while failing to accept that all that hassle resulted in nothing is rather unbecoming of those who are vociferously demanding the ban. Truth is that the perception, ranking and incidences of corruption remain the same or have changed little in India. What did happen was the tremendous discomfort caused to the populace, who had to stand in queues for days to exchange their banned notes for freshly issued one. Banks resorted to hoarding cash, making everyday life difficult. Those who had made their money through illegal means parked their banned money in alternative means (jewellery, property, expensive cars) and remained largely unperturbed. In carrying out this experiment, Modi’s government failed to grasp any lessons from similar experiments in India in 1946 and 1978, which also had little impact. Not to mention that curtailing the money supply shaved an estimated two percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth in India, a considerable figure given that India’s total GDP stands at more than $ 2 trillion these days.

In Pakistan, as per State Bank’s figures (August 2018 Statistical Bulletin), Pakistan’s total monetary base is Rs5.484 trillion, of which Rs4.38 trillion is currency in circulation, meaning that almost 80 percent of total money is in cash. This indicates an exceptionally high preference for cash and economic activity is heavily dependent upon it. How much of this cash is Rs5,000 notes? Nobody knows and neither is the SBP telling. In December 2016, when the Senate passed the resolution for banning the Rs5,000 note, the law minister informed that a staggering 30 percent of the total money in circulation consists of these notes. Taking the same percentage (it is highly unlikely that the percentage has changed much) as prevalent today, it would imply that Rs1.3 trillion of total cash in the economy consists of Rs5,000 notes.

Consider for a moment what would happen if all these Rs5,000 notes are banned overnight. First, the horror scenario: Rs1.3 trillion would become worthless in a day. As money supply is curtailed or disrupted, an already struggling economy will struggle further as it faces the spectre of very low growth rates. Forgers and black marketers would have a ball and economic agents (people, households and businesses) would find it difficult to get cash as hoarding ensues. Fake currency would flood the market and the rupee’s value could go down significantly, setting a bout of high inflation in process. As business activity dips, unemployment will rise as employers (especially in the informal sector) curtail their activities. If this scenario is realised, then poverty and inequality would spike further and government’s revenue will suffer as tax revenue declines.

Best case scenario? The government will print enough small denomination money to replace the Rs1.3 trillion denominated in Rs5,000. Still, people will have to queue up in front of banks for days, weeks or even months to get an equivalent amount for their Rs5,000 notes. Banks, as they usually do in times of economic stress, hoard cash. Given exceptionally high dependency upon cash transactions, the economy will take a long time to recover.

It is critically important to note an important aspect of this debate: the cost of printing money. In 2017, a SBP statement indicated incurring a cost of more than Rs9 billion to print notes of around Rs342 billion. These costs are incurred in terms of special printing machines, electricity bills for running those machines, special ink and special paper. These costs increase over time. Since large denominations lessen the cost through lesser quantity of printed money, the straightforward implication is that doing away with Rs5,000 note would increase that cost significantly. For the sake of simplicity, just take the above stated expense (Rs9 billion). If Rs342 billion incurs a printing cost of Rs9 billion, then printing Rs1.3 trillion in smaller denomination money to replace Rs5,000 would imply a cost exceeding Rs35 billion. Ultimately, these costs are recouped through the users or consumers in one way or the other. This means that people will have to ultimately bear the additional costs of printing smaller denomination notes.

The cost advantage and convenience conferred by large denomination bills is understandable when one looks at the monetary history and considers the cost of living. Increase in cost of living over time means that one has to pay more money over time for the same amount of stuff. Pakistan is no exception to this reality. Suppose now that decision makers had decided long ago, in the days of half anna and 1 rupee, that no bigger denomination than Rs1 will be printed. In 2018, this would mean that buying a car worth Rs20 lakh or more would need truckloads of cash to be delivered to the dealer or seller. Just imagine the hassle, bother and trouble one would have to go through to make that arrangement. It is exactly to avoid these kinds of hassles that large denomination notes come into existence over time, be it the Rs500 (1986), Rs1,000 (1987) or Rs 5,000 (2006).

Am I suggesting that banning the Rs5,000 note is a bad idea? No, not at all. I am simply asking a simple question: do we as a society understand the implications, costs and benefits of such a decision?

The writer is an economist and can be reached on Twitter @ShahidMohmand79