Cult Classic:

noun: Something, typically a film or book, that is popular or fashionable among a particular group or section of society.

(Oxford Dictionary)

This definition is not incorrect, but it is somewhat limited. Cult classics are only occasionally about art that is good but not appreciated by enough people. But some unappreciated art begins to gather a dedicated following which may provide it the mainstream appreciation that it initially deserved. However, largely cult classics are about art that is so bad that groups of people actually begin to build a fan base around it. Mostly because the artist is not conscious or aware about his art’s ‘badness.’ He/she earnestly believes that they have created something special. Something that can stand alongside the best there is in their field of art.

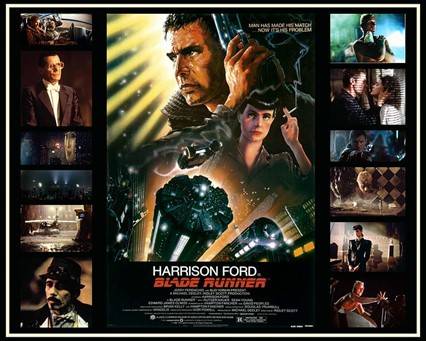

Regarding films, there are many good movies which bombed at the box-office. But years later, they were ‘rediscovered,’ reassessed and declared ‘great.’ Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) is a good example. It bombed at the box-office but thanks to the rise of the VCR and the VHS tape, the film began to attract a larger audience, especially when it turned up on what were called ‘laser discs,’ VCDs and then the DVD. It eventually began to be seen as a great piece of dystopian sci-fi, so much so that there are now at least five ‘cuts’ of the film with slight plot variations, and additional scenes. A dedicated Blade Runner fan is likely to own all five cuts. I do.

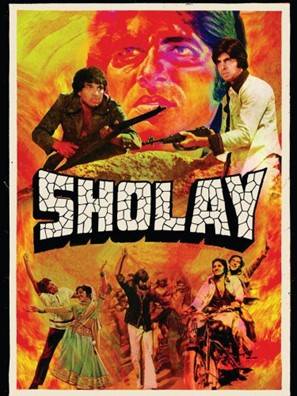

There are many other, similar examples. One of the most interesting is 1975’s Bollywood film Sholay. Yes, it went on to become one of India’s highest grossing films, but initially it was a flop. However, it steadily began to gather dedicated fans who watched it over and over again in cinemas. This created a buzz in the media. Cinema-owners and the ‘show-biz press’ couldn’t figure out why some people were returning to watch it, when the film was clearly not doing well. Sholay became a cult classic right from the onset when the media reported that certain groups of people were watching it repeatedly and had memorised many of the film’s dialogues.

It was this ‘cult’ phenomenon that made many others go see the film and find out what all the commotion was about. Then bang! After months of failing to attract a larger audience, Sholay rose to become a massive hit. It was released in 1975. Ten years later, in 1985, when I first visited India, Sholay was still playing in certain cinemas of Mumbai!

But these were good films made by established directors and had in them popular actors. Some good films that don’t do well at the box-office are either ahead of their time, or are unfortunate to have been reviewed by intellectually lazy critics. Or they fail to compete with other ‘big’ releases. But there is every possibility of them being resurrected by a growing cult following which can elevate their status and give them the kudos that they actually deserved.

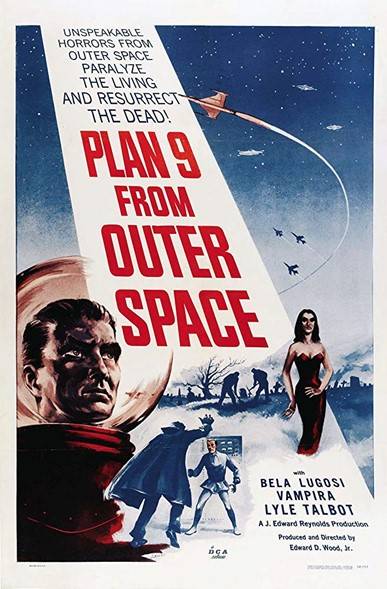

Yet, it is the bad films that manage to attract a dedicated following that dominate the realm of cult classics. These films were made in all seriousness and the makers really believed they were creating a ‘great’ piece of cinema. One of the most prominent examples is 1959’s Plan 9 From Outer Space. It is a constant in every ‘worst films ever made’ list. Yet, it has one of the largest cult followings. It was directed by the prolific filmmaker Ed Wood who, on viewing the film in a cinema, shed tears. To him, he had created a sci-fi masterpiece with deep meaning and emotions.

The reality was quite the opposite. The direction, the script, the acting and the special effects were terrible and drew laughter from those who watched it. It was unintentionally hilarious. And this is what made it a cult classic. The other factor that endeared Wood to so many admirers was the ‘passion’ and emotion that he invested in making his ‘masterpiece,’ entirely unaware of the fact that he had made a film that was terrible. Thus the phrase, “it is so bad that it is good.”

In 2002, I understood the endearment bit. I was a concept-writer at an advertising agency and my first assignment there was to pen a concept for a chewing gum brand. But the Creative Director (CD) scrapped my concept and wrote one himself. After an hour or so, he summoned me to his office to read me the concept that he had written. He asked me to ‘learn’ how ‘proper’ concepts are conceived.

He visualised a family (a father, a mother and their young son and daughter) on a bus. The bus stops somewhere and a man boards it. He is a chewing gum seller. As the bus starts to move again, the man breaks into a song. The lyrics: “Bubble banaien, sab mil kar khaien, mummy, papa laien …” (Let’s make bubbles, everyone will eat [chewing gum] togather, mummy, papa will get it …). Then the young son stands up and says (to the chewing gum seller), “bubble walay, bubble walley, humien aik bubble doh” (bubble-seller, bubble-seller, give me a bubble). And after the kid completes the sentence, the father exclaims, “hieennn ….!” I couldn’t help but burst out laughing. I thought the CD was parodying a ‘typical’ cliched advertising jingle. But he wasn’t. He was deadly serious. His nostrils flared and he turned red in the face.

Then it struck me. He was so emotionally invested in what he had created and yet, so unaware that he had dished out a super silly concept, that I actually ended up admiring him! The concept was instantly rejected by the client, but it quickly gathered a cult following in the office. The CD felt proud. To him, the client had rejected a brilliant concept and everybody in the office had become its fans. Yes, we had become fans. Not of the concept’s ‘brilliance’ but of its sheer idiocy which was so passionately pitched to the client by its creator. To this day, I often hum those lyrics. “Bubble banaien, sab mil kar khaien, mummy, papa laien …”

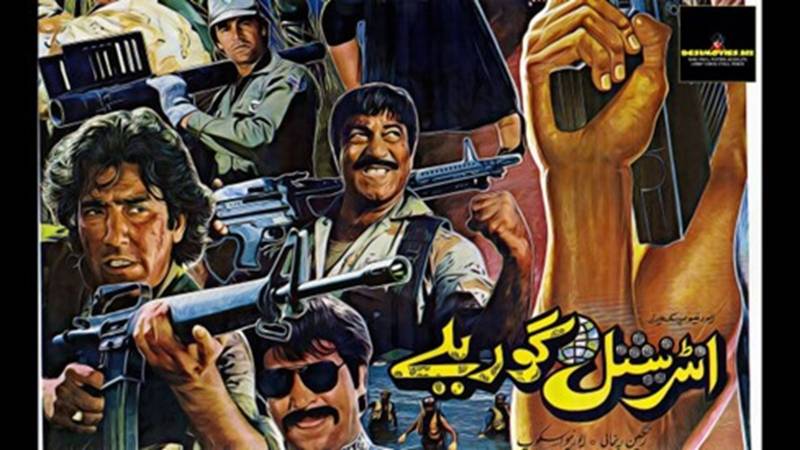

IG was perhaps the last Pakistani film that roused interest in international media. It wasn’t Oscar stuff, but it has remained to be a much-loved cult classic

In Pakistan, leading the list of 'so bad that it's good' cult classics has to be 1990’s International Gorrilay (IG). It was a box-office hit but soon forgotten. In the early 2000s, a now defunct website called Hot Spot published some pics and synopsis of the film. This attracted the interest of a whole new generation. Therefore, IG was re-released on the VCD format and started to gain a large circle of fans who would passionately discuss it on various internet forums.

IG is a masterpiece of unintentional hilarity. It’s silly, shoddy and bad in every sense of the word. The film is a celebration of a post-Afghan-jihad resurgence of the then Pakistani state’s belief that the country was a 'fortress of Islam.' IG was a hit when it was released in 1990 and, as mentioned, has become a cult classic among cinema aficionados. It was directed and plotted by Jan Muhammad, who then went on to direct delicious Lollywood rom-coms such as “Kuriyoon koh dalay dana” (Immidiate translation: Feeds women seeds).

Very few now remember that the film was banned in Britain because its villain was the novelist Salman Rushdie. But the ban was lifted when Rushdie himself stepped in and asked the British censor board to allow its release (on video). The film is so ridiculously tacky, one can understand why Rushdie didn’t feel offended by it. Jan Muhammad’s initial intent was to cash-in on the high Pakistan was experiencing after the retreat of the battered Soviet forces from Afghanistan and the ‘victory of the Afghan jihad.’ Jan’s original plot for the film was a lot wider, revolving around a group of Pakistani mujahids fighting in Afghanistan. But Jan quickly altered the plot when Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses created a huge controversy in 1989. This is when Jan decided to make Rushdie the film’s main villain.

Therefore, instead of showing mujahids returning from fighting a successful 'jihad' against communists, the film kicks off by showing Pakistan in the grip of a grave moral crisis due to the evil schemes of a sinister lobby of diabolical men. The lobby is led by Rushdie. He is played by the veteran actor Afzal Ahmed. In the film, Rushdie has started to lead a menacing onslaught on Islam. With him in the lobby are some very South-Asian-looking men, but in curly blonde wigs. Apparently, they are Zionists working for a secret Israeli agency.

Since Pakistan is the leading defender of Islam, the film suggests that if Pakistan falls to Rushdie's menacing schemes, so shall the rest of the Islamic world. Interestingly, Rushdie's assault on Islam includes the spontaneous opening of a chain of casinos and discotheques in Pakistan. Or was it the Philippines? One is not sure because it is in the Philippines where Rushdie is operating from. Why Philippines? No idea.

There is soon a heroic reaction to such conspiratorial debauchery. The veteran Punjabi film actor, Mustafa Qureshi, playing an ex-cop, decides to create a “mujahid fauj” (Jihad army) whose sole aim is to destroy Rushdie and 'save Islam and Pakistan' from blonde Zionist conspirators. And, of course, from immorality. The latter is a vital plot tool, giving the director the opportunity to show some lecherous dance scenes without the danger of making himself and the audience look like soft-porn fans. They’re just observing what debartury looks (and dances) like, y’know.

By the way, apart from popularising gambling, alcohol and disco music, Rushdie is also a master torturer. He torments captive Muslims by making them listen to sections of his cursed novel. I’m not making this up.

To counter Rushdie, ex-cop Qureshi inducts three of his younger brothers in his mujahid force. All three are unemployed — maybe because jobs in Pakistan are now only offered by casinos, bars and nightclubs? Perhaps. Anyway, after getting military training from their elder brother, the three-men-army decides to infiltrate Rushdie’s baleful gang by going undercover. They do this by slipping into Batman costumes. Obviously, who would notice three middle-aged men in Batman costumes, right? Right.

Two of the brothers are played by film actors Javed Shaikh and Ghulam Mohiuddin. Both were in their forties at the time, a fact underlined by the shape and size of their forty-something bellies, protruding from their Batman costumes. After making their way into the conspiring gang of anti-Islam thugs, the three brothers – with the help of karate chops, expert gun slinging, and a few American SAM missiles – make a meal of Rushdie and Co. and save Pakistan (and thus Islam). But it is the sudden appearance of three giant copies of Islam’s holy book which simultaneously fire red rays at Rushdie, turning him into ash.

What’s more, the brothers even manage to convert Rushdie’s equally evil mistress called Dolly (played by the lovely Babra Sharif). Voluptuous, wicked, scheming (and drunk), Dolly finally sees the light (quite literally), after witnessing the wrath of morality (attired in Batman suits) obliterate Rushdie’s gang.

Her conversion is quite the scene. Lights flicker, there is thunder, the room whirls round and round, and the orchestral music hits a peak as she weeps, sweats and shakes. It’s as if she has consumed (and was overdosing on) magic mushrooms.

IG was perhaps the last Pakistani film that roused interest in international media. It wasn’t Oscar stuff, but it has remained to be a much-loved cult classic. It is a great piece of campy cinema that only an idiot can take seriously, or as anything beyond being an unintentionally hilarious cinematic farce. But then, since most extremists are willing idiots, I was wondering if, due to IG’s bombastic reactionary antics, it actually ended up inspiring any future militants and vigilantes? The kind we increasingly began to see from the early 2000s onwards. The film was such a hit that a sequel of sorts was released in 1996. The sequel has its own following, even though it’s not as large as the one IG enjoys.

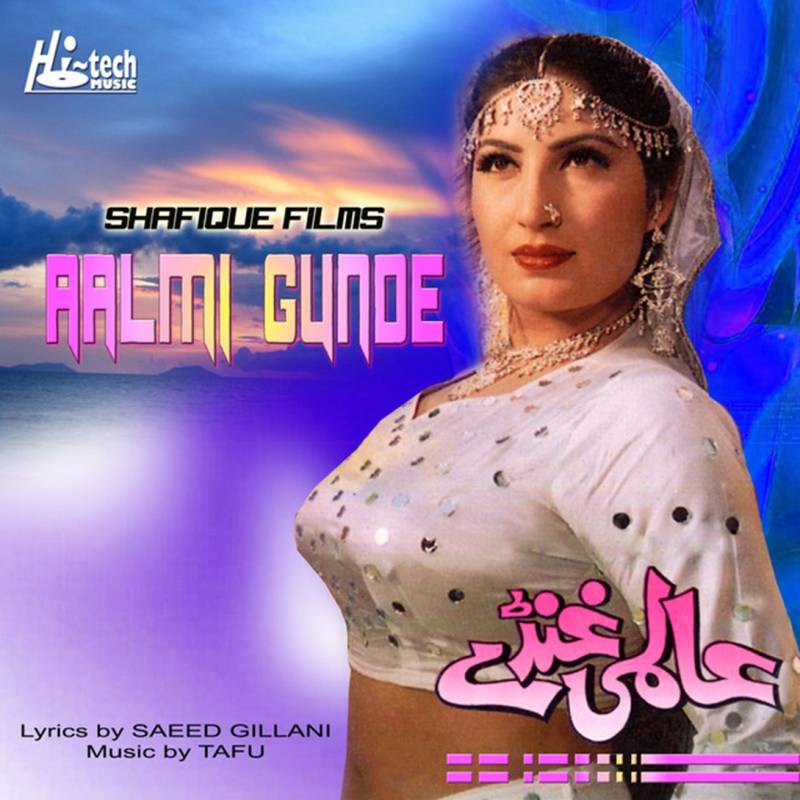

It was called Almi Ghunday (International Scoundrels). Even though it was directed by a different director and had different performers, the film more-than-alludes to the happenings in IG. Many years after Pakistan (and thus Islam) were saved from Rushdie and his gang of blonde-wigged Zionist thugs, yet another anti-Pakistan (and thus anti-Islam) villain has risen (played by Shaukat Cheema). His mission too is to harm Pakistan (and thus Islam) with the help of diabolical schemes and voluptuous disco dancing and binge drinking. Oh, and this one too is in a curly blonde wig.

A group of passionate ‘young men’ (albeit in their mid/late-forties) and a damsel in distress take on the evil Cheema but are arrested by cops along with the damsel’s frail old father. The government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has sold out to the greedy ways of Cheema’s sinister empire, and the frail father is dragged to the Supreme Court.

Here begins a terrific court scene. In it, the damsel - in a red dress that is a freaky cross between the Wonder Woman costume and a red desert tent - is seen fervently arguing with a lawyer who wants the old man hanged. She condemns the spread of obscenity, and laments about the practice of dishing out law according to 'ghair mulki' (non-Pakistani and thus non-Islamic) law books. Incidentally, a pile of such infidel books are neatly stacked in front of the bewildered judge (played by Munawar Saeed).

The damsel then lurches forward, lifts the books and flings them high into the air (in slow-motion), pleading that the prisoner’s case should be heard according to 'Islami qanoon' (Islamic law). The sort of qanoon which would first and foremost book her for her delicious sense of fashion, but that’s beside the point.

The judge suddenly sees the light and he flings out whatever books are left on the table and decides to hear the case according to ‘Islamic law.’ After a lot of shouting and flinging, the old man is released, and the group is given the green signal by the now-reformed state of Pakistan to go forth and demolish the wicked whisky-drinking blonde villain.

The film is a strangely disturbing example of a populist farce glorifying exactly the kind of self-righteous, convoluted and delusional mindset that is now the norm in Pakistan. The thought that such films were made for the 'masses' made me shudder.

Here as well I wonder as to whether some people took such films seriously. Or worse, were there those who actually decided to act upon the message that the film was delivering, which, in a nutshell, was that anyone and anything that is not according to an entirely binary understanding of faith and morality is up for spontaneous destruction, never mind the crazy Wonder Woman costumes?

Well, the mujahids in this film — this time in Robin Hood costumes — blow the evil man’s empire to smithereens and once again save Pakistan (and thus Islam) from the evils of alcohol, disco dancing and ghair mulki law.

The End.