In the handful of reviews of Sarvat Hasin’s first novel This Wide Night published online so far, most reviewers have ended up drawing lazy comparisons to Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women. The dust jacket description doesn’t do the novel any favour either, terming it a retelling of Little Women and The Virgin Suicides set in Karachi. Granted that the structure very closely resembles Little Women, such a reading not only denies the author her own creative intervention, but also impairs the critic’s ability to judge the novel for its own merits and, in this case, some lost opportunities.

Set in the 1970s, This Wide Night is about the four Malik sisters — Maria, Ayesha, Bina and Leila — who live with their mother, Mehrunissa, while their father, a Captain in the navy, is away on duty.

It is a novel about an unconventional family, hard-earned freedoms, absences and the irreconcilable yearning to anchor oneself on one hand and to unshackle societal chains to achieve complete freedom on the other.

Told in a conventional three-act structure, the first part is narrated, in a languorous tempo, by Jimmy, a boy who lives with his grandfather across from the Maliks, and who was orphaned as an infant. A sensitive observer and somewhat effeminate, Jimmy lets the readers into the Malik household and affords them a glimpse of the delightful freedom that the Malik sisters are afforded in the absence of a patriarch. Hasin exercises astute control by keeping the narrative tightly limited to an enclosed, domestic sphere. This in turn reveals how un-tethered the Malik sisters’ lives are to the outer world.

Jimmy befriends Ayesha, the most outspoken of the girls, and is eventually invited into the house. The meetings continue and the girls are at enough ease with his presence for Jimmy to tell us “they moved around me like I wasn’t there.” It is through these daily interactions that Jimmy’s friendship with the girls, especially Ayesha, is cemented. There are nuggets of foreshadowing cleverly dispersed throughout the first section, but what looms large over the entire section is Jimmy’s palpable loneliness, anxiety and sheer disbelief at being allowed such intimacy with the sisters. The disbelief gradually turns into a fear of this tenuous connection being broken. And it does — although as a consequence of a paper-thin subplot that is entirely forgettable.

The slow pace of narration here might prove difficult for some readers initially, but such prose with its closely observed details serves the novel best. For example, here is a small image slipped in amongst many others describing the changes girls are forced to make on Captain Malik’s arrival: “the ends of [the dupatta] frayed from where she’d caught it underfoot.” This is all Hasin requires to convey the sisters’ unease. There are numerous such phrasal fragments that, without stating much, signify a lot.

However, there are a few lazy slips like, “when Jimmy arrived on the scene” or the imprecise, “felt an unimaginable grief.” Even on the other end of the poetic extreme, one comes across laboured phrases like, “Lovely not the way the Malik women were with their willow-tree bodies and rivers of hair” or “…the weather on Ayesha’s face, blue skies when it went well and monsoon storms when it went badly.” Taken together, there are enough of these scattered throughout the novel to become obtrusive in the otherwise sharp and taut prose.

Shifting to a third person-omniscient view, we follow Jimmy’s life in London in the second section of the novel. We have read this before: the male protagonist, away from home, struggles to blend in, is unable to forget his past relationships and becomes lonelier than before. Nothing out of the ordinary. Though, here, too, it must be noted that despite there being passing references to the war back home, Hasin exhibits self-discipline by keeping this in the background and our focus firmly on Jimmy and the Malik sisters.

The novelty in this section lies in the scenes which follow Ayesha in Karachi, as she, without Jimmy to drive her around, learns to drive and makes sharp observations about the city and her relationship with it. We are told she finds herself in “a city she only knew through houses and bookshops and school, nothing learned of its streets or secrets.” She registers the overwhelming presence of boys in the city, and realises that she hasn’t met anyone in the city (whether carpenters or tailors) that she hadn’t known all her life. Any interaction with the city Ayesha makes is countered by it. Her driving instructor, for instance, while complaining to Mehrunissa about Ayesha’s fast driving, suggests that she be married before “she gets into too much trouble.” A callous suggestion that Mehrunissa deftly wards off (in stark contrast to Captain Malik, who, later in the novel, remarks “I won’t subject them to the eyes of people any more…They watch my daughters like they’re zoo animals, all these men talking and these hissing women.”)

But before Ayesha’s attempts to get closer to Karachi’s “streets and secrets” are allowed to evolve into something more riveting, the demands of a pre-determined plot strike again and Hasin leads us back to Jimmy’s doomed attempts at escaping his past.

We find Jimmy holidaying in Paris where he comes across Leila, who gets a fuller treatment this time, beyond just cursory remarks about her painting. It’s as if her eccentricity had been waiting for an absence around her to come out bursting through the seams. It is in Paris where the relationship between characters and the city is most firmly established. Both Jimmy and Leila are away from home, both feel a certain lightness; a suspension of boundaries that had kept them restrained earlier. Both end up marrying each other (this shouldn’t come as a surprise for those even vaguely familiar with Little Women’s plot.)

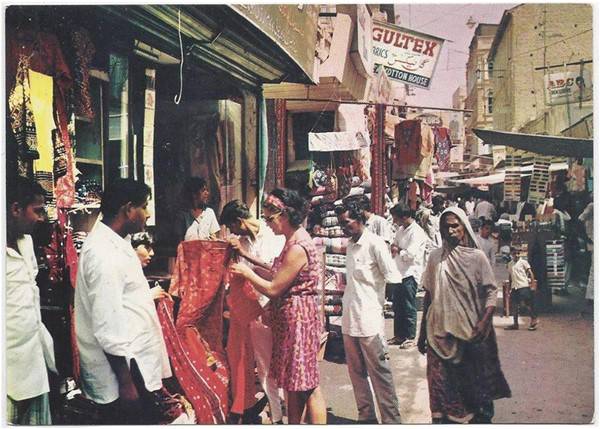

Hasin recently complained in an interview that writers who set their stories in certain cities are expected to explain the city. Her point is a valid one that can’t be casually dismissed, but the relationship of characters with the city they inhabit must still be well-defined. Given the many cities Jimmy occupies in the novel, the passages set in Karachi come across, unfortunately, as the weakest. Places like Empress Market and Metropole consistently clutter the novel, but these references merely function to dress up the lack of any expansive or deep engagement with Karachi as a city that Jimmy encounters, navigates and interacts with, and fails to chart out how his relationship with the city evolves over time. Even late into the novel, when Jimmy starts working in Karachi, one feels these events could be taking place in any city (and not the one he grew up in) — and that certainly isn’t a virtue.

It is when Jimmy returns home with Leila that the novel stumbles onto its most appealing aspect and asks us its most enduring questions. This is where Jimmy’s longing for filling an absence in his life comes most sharply in focus, falling tragically at odds with the sisters’ desire to remain free. Even when living with the Malik sisters, Jimmy confesses that “a veil of womanness” had always separated them from him. Jimmy’s attempts to get closer to the Malik sisters prompts Ayesha to say, “You know the problem with people who go away is that they spend so much time thinking of all that’s gone differently in their lives, and no time at all thinking of how other people might have changed. You come back and you expect us all to be here, just waiting for you in our places.”

What began as an imitative performance, by the end, turns into a quiet reflection, at least in brief inspired bursts, on separation and how we respond to absences in our lives.

It is, then, slightly disappointing that Hasin chooses not to pursue this thread more deeply, favouring instead a hastily treated and predictable ending, the lead-up to which is far more haunting and absorbing.

As the clang and clamour of supposedly unputdownable thrillers recedes, this is the kind of novel that deserves our time and attention. The dust jacket description might not have got everything right, but is spot on when it calls This Wide Night a compelling new novel.

Set in the 1970s, This Wide Night is about the four Malik sisters — Maria, Ayesha, Bina and Leila — who live with their mother, Mehrunissa, while their father, a Captain in the navy, is away on duty.

It is a novel about an unconventional family, hard-earned freedoms, absences and the irreconcilable yearning to anchor oneself on one hand and to unshackle societal chains to achieve complete freedom on the other.

Told in a conventional three-act structure, the first part is narrated, in a languorous tempo, by Jimmy, a boy who lives with his grandfather across from the Maliks, and who was orphaned as an infant. A sensitive observer and somewhat effeminate, Jimmy lets the readers into the Malik household and affords them a glimpse of the delightful freedom that the Malik sisters are afforded in the absence of a patriarch. Hasin exercises astute control by keeping the narrative tightly limited to an enclosed, domestic sphere. This in turn reveals how un-tethered the Malik sisters’ lives are to the outer world.

Jimmy befriends Ayesha, the most outspoken of the girls, and is eventually invited into the house. The meetings continue and the girls are at enough ease with his presence for Jimmy to tell us “they moved around me like I wasn’t there.” It is through these daily interactions that Jimmy’s friendship with the girls, especially Ayesha, is cemented. There are nuggets of foreshadowing cleverly dispersed throughout the first section, but what looms large over the entire section is Jimmy’s palpable loneliness, anxiety and sheer disbelief at being allowed such intimacy with the sisters. The disbelief gradually turns into a fear of this tenuous connection being broken. And it does — although as a consequence of a paper-thin subplot that is entirely forgettable.

The slow pace of narration here might prove difficult for some readers initially, but such prose with its closely observed details serves the novel best. For example, here is a small image slipped in amongst many others describing the changes girls are forced to make on Captain Malik’s arrival: “the ends of [the dupatta] frayed from where she’d caught it underfoot.” This is all Hasin requires to convey the sisters’ unease. There are numerous such phrasal fragments that, without stating much, signify a lot.

However, there are a few lazy slips like, “when Jimmy arrived on the scene” or the imprecise, “felt an unimaginable grief.” Even on the other end of the poetic extreme, one comes across laboured phrases like, “Lovely not the way the Malik women were with their willow-tree bodies and rivers of hair” or “…the weather on Ayesha’s face, blue skies when it went well and monsoon storms when it went badly.” Taken together, there are enough of these scattered throughout the novel to become obtrusive in the otherwise sharp and taut prose.

Shifting to a third person-omniscient view, we follow Jimmy’s life in London in the second section of the novel. We have read this before: the male protagonist, away from home, struggles to blend in, is unable to forget his past relationships and becomes lonelier than before. Nothing out of the ordinary. Though, here, too, it must be noted that despite there being passing references to the war back home, Hasin exhibits self-discipline by keeping this in the background and our focus firmly on Jimmy and the Malik sisters.

The novelty in this section lies in the scenes which follow Ayesha in Karachi, as she, without Jimmy to drive her around, learns to drive and makes sharp observations about the city and her relationship with it. We are told she finds herself in “a city she only knew through houses and bookshops and school, nothing learned of its streets or secrets.” She registers the overwhelming presence of boys in the city, and realises that she hasn’t met anyone in the city (whether carpenters or tailors) that she hadn’t known all her life. Any interaction with the city Ayesha makes is countered by it. Her driving instructor, for instance, while complaining to Mehrunissa about Ayesha’s fast driving, suggests that she be married before “she gets into too much trouble.” A callous suggestion that Mehrunissa deftly wards off (in stark contrast to Captain Malik, who, later in the novel, remarks “I won’t subject them to the eyes of people any more…They watch my daughters like they’re zoo animals, all these men talking and these hissing women.”)

Hasin recently complained in an interview that writers who set their stories in certain cities are expected to explain the city

But before Ayesha’s attempts to get closer to Karachi’s “streets and secrets” are allowed to evolve into something more riveting, the demands of a pre-determined plot strike again and Hasin leads us back to Jimmy’s doomed attempts at escaping his past.

We find Jimmy holidaying in Paris where he comes across Leila, who gets a fuller treatment this time, beyond just cursory remarks about her painting. It’s as if her eccentricity had been waiting for an absence around her to come out bursting through the seams. It is in Paris where the relationship between characters and the city is most firmly established. Both Jimmy and Leila are away from home, both feel a certain lightness; a suspension of boundaries that had kept them restrained earlier. Both end up marrying each other (this shouldn’t come as a surprise for those even vaguely familiar with Little Women’s plot.)

Hasin recently complained in an interview that writers who set their stories in certain cities are expected to explain the city. Her point is a valid one that can’t be casually dismissed, but the relationship of characters with the city they inhabit must still be well-defined. Given the many cities Jimmy occupies in the novel, the passages set in Karachi come across, unfortunately, as the weakest. Places like Empress Market and Metropole consistently clutter the novel, but these references merely function to dress up the lack of any expansive or deep engagement with Karachi as a city that Jimmy encounters, navigates and interacts with, and fails to chart out how his relationship with the city evolves over time. Even late into the novel, when Jimmy starts working in Karachi, one feels these events could be taking place in any city (and not the one he grew up in) — and that certainly isn’t a virtue.

It is when Jimmy returns home with Leila that the novel stumbles onto its most appealing aspect and asks us its most enduring questions. This is where Jimmy’s longing for filling an absence in his life comes most sharply in focus, falling tragically at odds with the sisters’ desire to remain free. Even when living with the Malik sisters, Jimmy confesses that “a veil of womanness” had always separated them from him. Jimmy’s attempts to get closer to the Malik sisters prompts Ayesha to say, “You know the problem with people who go away is that they spend so much time thinking of all that’s gone differently in their lives, and no time at all thinking of how other people might have changed. You come back and you expect us all to be here, just waiting for you in our places.”

What began as an imitative performance, by the end, turns into a quiet reflection, at least in brief inspired bursts, on separation and how we respond to absences in our lives.

It is, then, slightly disappointing that Hasin chooses not to pursue this thread more deeply, favouring instead a hastily treated and predictable ending, the lead-up to which is far more haunting and absorbing.

As the clang and clamour of supposedly unputdownable thrillers recedes, this is the kind of novel that deserves our time and attention. The dust jacket description might not have got everything right, but is spot on when it calls This Wide Night a compelling new novel.