On the basis of available evidence, we can safely conclude that Imran Khan has emerged as the third political leader in Pakistan’s history who has succeeded in transcending ethnic boundaries. Before him, Zulifiqar Ali Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto had achieved this feat. What exactly is meant by transcending ethnic boundaries?

Pakistan is a federation and each federating unit comprises, more or less, an ethnic nationality. When a leader crosses the borders of their home ethnic community and gains popularity in another ethnic nationality, it means they have transcended ethnic boundaries in the context of Pakistani politics.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s home constituency was obviously Sindh, but he built a strong popular base in Punjab. Benazir Bhutto was equally popular in Punjab and Sindh. Nawaz Sharif, on the other hand, never succeeded in transcending ethnic boundaries—his popularity has remained restricted to central Punjab throughout his political career. Now Imran Khan seems to be at the apex of his popularity in Central Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

There are also emerging signs that he is gaining popularity among the Urdu speaking population of Karachi. Pakistan’s strong headed establishment will do a service to Pakistani nationalism’s cause if it starts to see a silver lining in political developments related to PTI’s intermittent protest movements since Imran Khan was ousted from power. We see protests in Peshawar, Lahore, Karachi and Quetta at the same time, which in practical terms would mean that Pashtun, Punjabi, Urdu speaking and Baloch respectively have started to think alike. At least there is some point of convergence between these ethnic communities, which, otherwise always tread on parallel paths—paths which seldom converge.

Pakistan’s strong headed establishment has very little capacity to understand the intricacies of politics.

We should not underestimate the value of this convergence. This convergence means that the feeling of being a Pakistani—a feeling which apparently is manifesting itself in the love for the persona of Imran Khan - is being channelized into a political cause. May 9 may have been despicably bad, but in its wake, political activity associated with Imran Khan and his incarceration has been peaceful.

Pakistan’s strong headed establishment has very little capacity to understand the intricacies of politics. It is time that the establishment understands that for a society, which has just come back from the brink of a civil war, political activity, if it is peaceful, is good, irrespective of the fact that the ubiquitous sentiment is deeply anti-establishment. Politics and political activity are especially good if they bring ethnic nationalities closer. When the Pashtuns are protesting on the same day when Punjabis are staging a protest and when both these communities, separately, are holding protests for the same cause, this is a positive development for the Pakistani federation and for the country.

History tells us that a sustained political process in a democracy always bears fruits for political structures, as well as the people of the country. But these fruits don’t fall from heaven; they have to be induced through a process of continuous reforms, a process that could put an end to Punjab-centric politics.

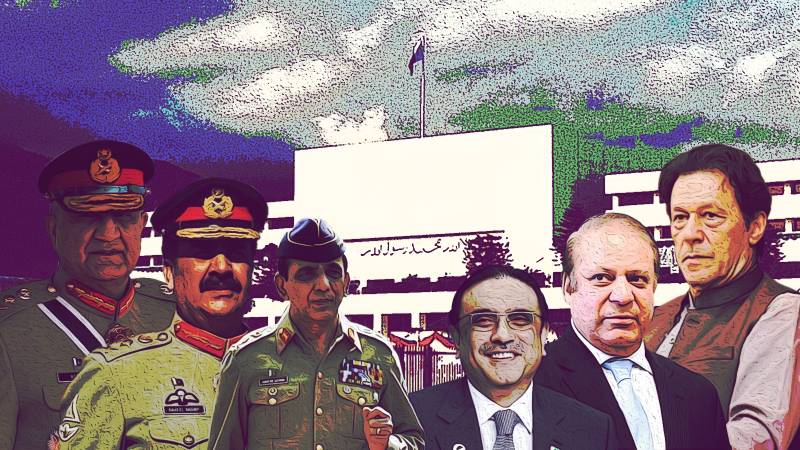

There is however a flip side to this development that is primarily taking at the grassroot level. The flipside is the triangular power struggle between Punjab-centric political forces in our society, which dominate the political and power structures in our country. There are three of these Punjab-centric political forces—the Pakistani military and its affiliated intelligence agencies, the former ruling party, Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI).

The Pakistani military is a Punjab centric political force primarily because its officers’ crops are drawn largely from the middle classes in Central Punjab. The Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) has its political stronghold in Central Punjab, from where it has won a majority in the National Assembly in general elections from 1993 till 2013 (the 2002 parliamentary elections were exception when PML-N didn’t secure a majority, as the country was being ruled by a military dictator). The PTI is a Punjab centric party because it won a majority in the National Assembly in the 2018 elections from Punjab. Imran Khan became Prime Minister in 2018 because he secured a majority from Punjab.

The political agenda of all three of these political forces is based on projecting the interests of Punjab and to a lesser extent that of the Punjabi middle classes. One could argue that the elder Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto both became Prime Ministers because of their majority in Punjab. If that stands true, then why are they not labelled as Punjab-centric. It was the political agenda of the house of Bhutto which distinguished them from other Punjab-centric political forces. The Bhutto brand of politics was immersed in the constitutional norms of the 1973 Constitution, which saw Pakistan as a federation and provincial autonomy was held as a central principle in the political system of the country. Of course, neither the elder Bhutto nor Benazir Bhutto succeeded in enforcing the autonomy of the federating units as governing philosophies during their tenures. But both are now perceived as heroes of provincial autonomy because of the peculiar political circumstances of their struggle against the military government of Zia-ul-Haq, during whose tenure opposition to provincial autonomy was the strongest in the power corridors in Islamabad and Rawalpindi.

The Pakistani political system has a structural flaw—that no one can become Prime Minister until they have secured a majority in Central Punjab, where the vast majority of the National Assembly seats are located.

Benazir Bhutto had an additional qualification as economic, social and political contradictions between Punjab and Sindh were automatically resolved within her personage during her tenures in office. Imran Khan and Nawaz Sharif’s rise to prominence in the country's politics was deeply dependent on non-representative institutions, which forms the bedrock of anti-federalism in Pakistani politics. Both started their careers as the blue-eyed darlings of spymasters and Army generals. During his tenure in office, Imran Khan displayed strong proclivities towards transforming Pakistan into a country with a strong center. Nawaz Sharif and the political structure he presides over is hardly capable of thinking beyond the interests of Central and Northern Punjab.

The Pakistani political system has a structural flaw—that no one can become Prime Minister until they have secured a majority in Central Punjab, where the vast majority of the National Assembly seats are located. This structural flaw makes every politician vying for the office of Prime Minister dependent on central Punjab for support. They have to cater to the demands of people and constituencies in Central Punjab in their campaign for election.

If any politician wants to retain these constituencies, they have to allocate a major share of the state’s resources to central Punjab—where the central battle for the Prime Minister’s office is fought. For example, none of the political leaders vying for Prime Minister’s office today have devoted much time to the issue of enforced disappearances in Baluchistan. Baluchistan is a far-off land, with no role in the making or breaking of federal governments, since the whole province has fewer seats in the National Assembly than Lahore division alone.

History tells us that a sustained political process in a democracy always bears fruits for political structures, as well as the people of the country. But these fruits don’t fall from heaven; they have to be induced through a process of continuous reforms, a process that could put an end to Punjab-centric politics. Instead of putting hurdles in the way of the PTI protest movement, a military, which has just dealt with and emerged from a civil war, should facilitate a political movement that has the potential to bring a diverse group of people on the same platform. The political process, in every form, should be welcomed.

A protest March from Quetta to Islamabad should be welcomed for its peacefulness and for its ambition to seek justice from Pakistan’s federal institutions. The political process, in the form of people expressing themselves freely in society, is vital for a state’s vibrancy, because it is this vibrancy which unites the people of Karachi, Peshawar, Quetta and Lahore. The protest movement against Imran Khan’s incarceration is a byproduct of the success of electronic and social media in Pakistani society.

To Pakistan’s establishment, I urge you to please let this vibrant political process flourish. Your strong headedness will only lead us to the wilderness.