How on Earth has he survived for so long?” I ask Saif-ul-Malook, Junaid Hafeez’s lawyer. “Books,” he responds. “Every week during their visitations, Junaid asks his father to bring a couple of books from his library at their next meeting. Those books are what’s kept him alive all this time.” For nearly eleven years, Junaid’s father has made the 200km journey from Rajanpur to New Central Jail Multan, to visit his son who has been languishing in solitary confinement for nearly a decade.

Who is Junaid Hafeez?

Growing up in near poverty, Junaid’s chances of success were little, if any. One of three siblings, his father worked in a printing press company barely managing to put all three children through school. Despite the poverty stricken circumstances, Junaid exhibited genius early on, and continued on that trajectory throughout his schooling. He received a gold medal in pre-medical studies, before deciding to pursue English literature at Bahaduddin Zakariya University (BZU) where he shattered a 38-year-old record by scoring a 3.99 GPA. Then, in 2009 he secured the highly coveted Fulbright Scholarship. The scholarship was awarded to a total of five students out of Pakistan’s 190 million population. Junaid was one of the five.

Junaid used the scholarship to complete his Masters in American literature, photography and theatre from Jackson State University, before returning to BZU as a visiting lecturer in the English department. A decade-old YouTube video shows an enthusiastic Junaid immersed in his theatre studies, playing characters such as Don Jackson in Zooman and the Sign – a play by Charles Fuller.

Junaid was on an all-time high. The boy from Rajanpur had surpassed all expectations. How far could he go? What fresh perspectives could he bring to the students of BZU? Junaid’s reason for coming back to Pakistan was simple: he wanted to provide a space where art, literature and theatre could flourish. A haven where creativity was encouraged, seminars on feminism were accessible, and critical thinking was supported. Then, in the blink of an eye, it all came crashing down.

Junaid’s presence at BZU and particularly his unabashed critique, challenge, and analysis of social norms had caused a stir among the more conservative elements of the University, namely the student wing of Jamaat-e-Islaami – a political party – and its derivative Tehrik-Tahafaz-e-Namoos-e-Risalat.

“Did he say anything?” I ask eagerly. “He smiled,” replies Mr Malook. Slightly disappointed, I ask if that’s all that Junaid did. “I haven’t seen him smile for months.” Mr Malook tells me. “You have no idea what that smile means for someone who has been in a death cell for that long. More than any words could ever convey”

Taunting him as a “liberal,” the groups decided they best stop Junaid, by preventing him from securing a permanent teaching position, when it opened at BZU. Junaid was, without a doubt, the most likely candidate to secure the post. What followed was a vile, targeted hate campaign that cost Junaid his freedom and hurled him into a black hole. The hate campaign accused Junaid of placing blasphemous pamphlets on a university noticeboard, making blasphemous comments at an academic seminar and, operating two Facebook groups where blasphemous content was posted. As blasphemy is a crime in Pakistan, Junaid was duly arrested on 13 March 2013. Six years later he received the death sentence after being convicted for blasphemy. Since 2014, Junaid has been held in solitary confinement due to repeated attacks from other prisoners. Junaid has denied all charges and accusations of blasphemy.

The rocky road to Justice

Finding legal representation was an uphill battle from the outset. Junaid’s first lawyer abandoned the case after receiving multiple death threats. It seemed all hope was lost, until one of Pakistan’s finest human rights lawyer, Rashid Rehman decided to defend Junaid. Mr Rehman also received multiple death threats, but refused to abandon Junaid. Shockingly, the last of these threats was made in an open court by the prosecution who told Mr Rehman that unless he abandoned Junaid, he would not make it to the next hearing. That threat was carried out on 7 May 2014, when Mr Rehman was murdered by two gunmen who stormed his chambers.

Similarly, finding judges willing to even hear the case continues to be an arduous task. From 2013 to 2019, a total of eight different judges heard Junaid’s case, making a fair trial near impossible. Furthermore, unreasonable delays by the prosecution also added to the fire.

All this has meant is that for almost five years, Junaid, his family, and counsel wait in a continuous limbo for the Lahore High Court to finally hear his appeal. Should the High Court reject Junaid’s appeal, they plan to approach the Supreme Court. However, the question is how long will that take? Another decade whilst Junaid’s mental and physical health deteriorates by the minute?

We cannot afford to be complacent at a time where all our influence needs to be used to ensure that Junaid receives a fair trial now - not tomorrow, not in ten years - but now.

Using collective action to save Junaid Hafeez

Although we cannot force the courts to hear the case immediately, a previous example does shine a light on what is possible when we choose to act collectively. Take Mr Malook’s most high-profile case, The State vs Asia Bibi. When Asia Bibi, a Pakistani Christian woman was sentenced to death for blasphemy, people around the world rallied in her support. Not only were there over 290,000 signatures challenging her conviction, but the case had also taken a focal position in diplomatic agendas as well, with Pope Francis also vouching for her acquittal.

Few could argue that such focused international coverage of the case weakened Asia Bibi’s chances of a fair trial. In fact, it was that pressure which helped ensure Asia Bibi’s case remained at the forefront of people’s minds. Junaid Hafeez deserves the same attention from all of us too.

Not only do we have a moral and ethical responsibility to do all we can to save Junaid Hafeez as we did with Asia Bibi, but as global citizens with access to multiple platforms to amplify our voices, there is simply zero excuse not to. Actively participating in human rights led diplomacy, raising awareness of Junaid’s case through social media and seminars and, ensuring our leaders and politicians are using their influence to speak up and keep Junaid’s case alive are all vital for keeping him at the forefront of our minds and agendas.

The maxim “justice delayed is justice denied” must be upheld vigorously by all of us to ensure that no further delays to hear Junaid’s appeal are allowed. After all, what it will cost us to speak out for Junaid, is far less than what it will cost Junaid if we choose not to speak out. By choosing not to raise our voices, we send a clear message that despite hearing his screams, we chose to cover our ears and close our eyes and, that we are fully willing to bear this dark stain on our collective human consciousness. It begs the question: Is this the legacy we wish to leave behind?

Hope in a death cell

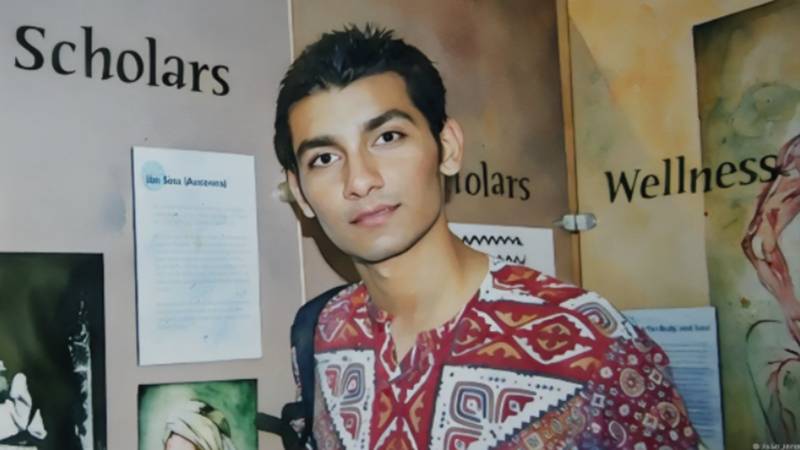

On a balmy summer evening I glance at Junaid’s photos. I am told by Mr Malook that Junaid does not resemble the smiling young man I see in the photos. Ten years in solitary confinement have taken a toll, he tells me. “I told him about you the other day by the way. That you’re helping me on his case, and you believe in his innocence,” Mr Malook tells me. “Did he say anything?” I ask eagerly. “He smiled,” replies Mr Malook. Slightly disappointed, I ask if that’s all that Junaid did. “I haven’t seen him smile for months.” Mr Malook tells me. “You have no idea what that smile means for someone who has been in a death cell for that long. More than any words could ever convey.”

Junaid may not be the young man we see smiling in pictures anymore. However, there is one thing he still possesses: hope. Hope that we will diligently fight for his justice, hope that one day he will walk free and, hope that he will get to live the life he was always meant to live. That glimmer of hope is one we cannot afford to lose.

In an inter-connected world where all it takes is the touch of a button for our voices to be heard, we must utilise our voices, power and influence to speak up and save Junaid Hafeez. To not condemn him to the abyss of hopelessness, but to collectively mobilise our compassion to boldly serve Junaid at a time where all hope was nearly lost.

It was Bob Marley who once said that the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing. Let our legacies not be that we allowed the triumph of evil to take the life of the genius from Rajanpur, but that we acted with vigour, determination and courage in the face of injustice to save an innocent life destined for so much more than a rope around his neck.