Last month, yet another conference on policy ‘reforms’ was organised by the World Bank and its local partners. This must be the umpteenth such moot to have debated on prescriptions to ‘fix’ Pakistan’s never ending ‘crisis.’ The stark truth is that the word ‘reform’ is perhaps the most cliched term among Pakistan’s policy elites and their international partners. Every other day, the necessity of reform is underscored by development institutions, think tanks, sections of the media and academia. Even politicians pay lip service on this front, and the bureaucrats in their notes mention reform as a panacea, an elixir, or a magic bullet.

Development practice and literature for the past many decades have emphasised that reform is inherently a political process. It is not a mere technical exercise or miraculous implementation of well-crafted strategies, boardroom deals or ‘ownership’ by individual champions. This is why the technocratic discourses underestimate and essentially remove the political process that potentially underwrites change.

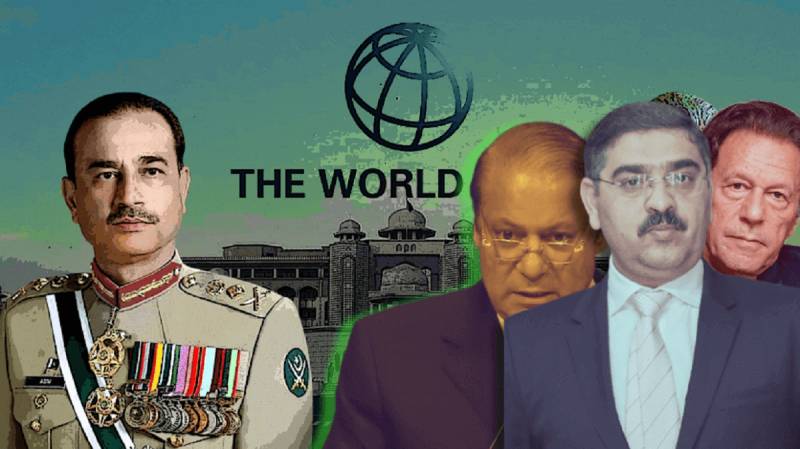

The intention here is not to berate well-intentioned international bureaucrats and policy enthusiasts in Pakistan. Knowledge production and public debates are valuable, and ideas matter. But, there is a structural issue with international development. The neoliberal financial institutions shy away from direct engagement with politics, and have found governance as a proxy to address the 'P' word. For even a small reform effort, there are political bargains, mobilisations and layers of ownership. Sadly, in Pakistan, there is little or no ownership of ‘change’ among the agents of the status quo, the civil-military bureaucracy and the senior judiciary. The political class is chained by its own financial interests, given the imperatives of patronage, rent-seeking, and finding generous allies in big business, real estate and corporate media.

Institutional change is an outcome of how the formal and the informal, the de facto and de jure decision makers interact and negotiate

In recent history, after 9/11, international coffers were opened for Pakistan to ‘reform’ under its moderately enlightened dictator. Granted that the Musharraf regime (1999-2008) did spearhead notable reforms in local government, civil service - especially the police - and many other areas. But, these efforts did not last long despite the generous donor support. Towards the end of Musharraf’s tenure, almost all the changes wrought by the regime had been nullified or at best diluted beyond recognition.

Following Musharraf’s exit, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan represented a reformist moment borne out of a political accord and it introduced a sweeping range of changes in the way Pakistan is governed. Most notably, the provinces were empowered with more functions and resources. Yet, the 18th-amendment agenda remains incomplete without devolution of power and resources at the local level; and shedding the size of the federal government. In fact, during the succeeding decade, the federal bureaucracy that runs any government, in effect, recentralised the ministries that had been devolved.

There are five preconditions to introducing and implementing reform: political consensus on a common minimum agenda; political leadership driving the effort; a long-range commitment of resources, legal and institutional reordering; public support and engagement; and a strategy to work with the cynics, the naysayers and the saboteurs. All these preconditions may not be there, but the political environment can make them achievable.

Is that the case in Pakistan? Certainly not.

Institutional change is an outcome of how the formal and the informal, the de facto and de jure decision makers interact and negotiate. Take the time horizon, for instance. The greatest source of de facto power is the military led by a chief appointed for three years. In the recent past, energies of such leaders have been spent on extending their term in office, and for that they are ready to manipulate the system in their favour, thereby ushering in more instability. They have little or no in-house expertise in complex issues of economic management, growth and social development. On the other hand, the political parties and their leaders are in constant battle to survive in office, avoid jail, or get re-elected and for that reason, their priorities are altogether different. On social development, they are tied to the idea of patronage and distributing goodies for electoral management. Within that patronage framework, spaces open up for service delivery improvements, but this is not always a guaranteed outcome.

Despite the massive propaganda against the political parties, the only segment of power-elite that may have a vested interest in change is the political class

More importantly, political contestations on issues of taxation impede any plan for change. For at least two decades, successive governments have tried to expand the tax net and make the traders pay more. All such efforts have failed. The World Bank itself has furnished hefty loans for a tax administration programme. This effort was halted for a while with uncertain results, but it was resumed. Why would it succeed now when the earlier programmatic interventions failed? And if the government wants extra dollars, then why this pretence of ‘reform’ by both the parties? This is just one illustration of the farce that repeats as a tragedy.

The third de facto player now is what is called the superior judiciary in Pakistan. While they have been central to the maintenance of civil-military bureaucratic hegemony, now they are autonomous players in the system. The most striking example was that of halting the 2006 privatisation of Pakistan Steel Mills under Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry. The same Court landed Pakistan into a royal mess on the Reko Diq project. Pakistani taxpayers have ended up paying for the grandiose posturing by judges who, to begin with, are ill-trained on policy matters, and overstep their jurisdiction in settling matters that the executive and the parliament ought to be handling. Data reveals that by the end of 2022, more than 88,317 tax cases worth Rs2.611 trillion were pending in different courts. These numbers have gone up, but the adjudication process is slow, and there are no signs that the executive or the judiciary are willing to see any kind of self-correction, let alone a packaged ‘reform’ programme.

Other de facto players are the cartels that have an inordinate influence on the policy process. The cement, sugar, forex, automobile, and real estate oligarchs to name a few demonstrate the classic signs of state capture. They have associates in the military, bureaucracy, and now they own a sizeable chunk of mainstream media.

Despite the massive propaganda against the political parties, the only segment of power-elite that may have a vested interest in change is the political class. The two redistributive programmes, Lady Health Workers and the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), have continued despite the change in governments. All three major political parties have displayed commitment to these welfarist networks in the past few decades.

Central to this process will be restructuring Pakistan from a national security state into a developmental state.

Political parties have a mandate too, and a legitimate claim under the Constitution, to govern and reform. But they are frequently absent from the policy discourse, and their in-house capacity is so anaemic that, once in power, are forced to hire conservative bureaucrats trained in the neoliberal institutions as economic managers, state bank governors and technical advisors. Despite this formidable constraint, the only way forward for reform is striving for a deliberative and well-negotiated consensus among the political elites. That can only take place if the political parties are allowed to function independently of the military diktat or a manufactured politics of polarisation. It is surely a little more complex than the popular reference to a ‘charter of economy’, but parliamentary process on the latter could be the starting point.

The international institutions, despite their enormous clout, cannot help achieve a political bargain. Nor can Pakistan’s friends in the Gulf. There are two ways in which this might happen. First, a crisis of such a magnitude that it restructures elite-behaviour, e.g., a default in the current scenario. Second, a civilian leader who goes out of the way to foster a grand dialogue between the power players and is not hindered by the militablishment in creating compacts between political forces. Neither a military saviour, nor a group of technical wizards can accomplish such results.

Pakistan’s battered civil society, heavily under pressure for more than a decade now, political workers and second and third tiers of leadership will have to push the political parties for moving towards a modicum of consensus on key areas such as local government, resizing the government, social development allocations and above all, climate action. Central to this process will be restructuring Pakistan from a national security state into a developmental state.

Notwithstanding the democratic backsliding during the last decade, it is still not too late for the political class to close their ranks and shun the politics of vendetta and settling scores. It is only through democratic politics that a diverse, complex country like Pakistan can reform itself.

There is no other way out.