On Pakistan Day, 23rd March, 2024, the foreign Minister of Pakistan, Mr. Ishaq Dar informed the media in a press conference in London that the Pakistan government was ‘seriously considering’ resumption of trade ties with India as Pakistani businessmen were pushing the government to open trade with India for reviving the worsening economic outlook of the country. But only a few days later, in a weekly press briefing on 28th March, Ms. Mumtaz Zahra Baloch, the Foreign Office spokesperson clarified there was no such plan under discussion.

Pakistan is perhaps one of the unique countries in the contemporary world which still blindly follows the classical realist paradigm and sacrifices its economic interests in the name of traditional security. In the twenty-first century, global trends show that following the complex interdependence principle, most of the countries of the world have delinked their trade relations with their adversaries with whom they have strategic and territorial conflicts. Despite territorial conflicts, historical adversaries now cooperate in regional settings and establish strong trade ties with each other.

The exponential growth of trade between China and USA, and China and India in last two decades has happened despite their longstanding strategic rivalry and conflicts. Since China’s entry into the WTO in 2001, US imports from China rose from $100 billion to $500 billion by 2022. On the other hand, the Indian embassy website in Beijing claims, ‘From 2015 to 2021, India-China bilateral trade grew by 75.30%, an average yearly growth of 12.55%.’ Despite a deadly conflict between India and China along the Kashmir border since 2020, India-China bilateral trade reached all-time high $136.2 billion in 2023.

Even trade between historical adversaries with border conflicts like Greece and Turkey, and Iran and Iraq have been growing during last two decades despite their historical unresolved longstanding territorial conflicts. Hence, most of the countries of the world now do not sacrifice their trade interests for the sake of their traditional security interests and longstanding territorial conflicts.

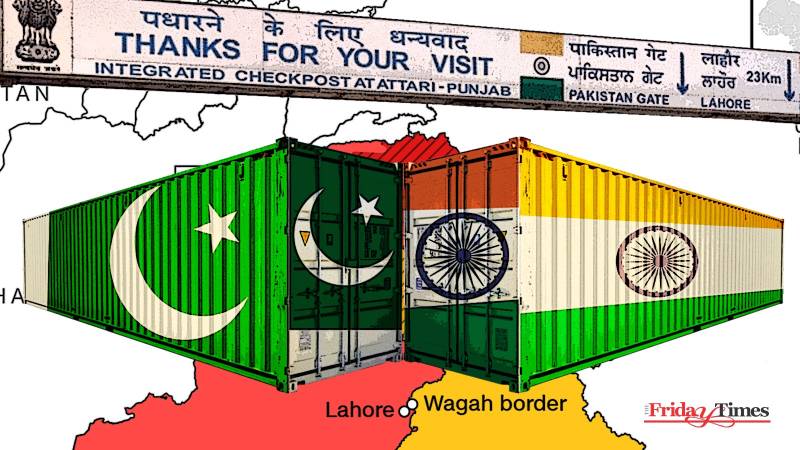

Because of the cultural proximity, the people of Pakistan and India share similar choices and preferences in terms of food, clothing, and entertainment industry etc. Therefore, experts in regional trade in South Asia believe if a politically conducive environment is created for trade, bilateral trade between India and Pakistan could multiply tenfold from the level it was in August 2019 when Pakistan suspended all bilateral trade with India. Pakistan had downgraded diplomatic relations with India and decided to completely suspend all kinds of trade with India because of the Modi government’s unilateral decision to revoke Article 370 and 35-A in Jammu and Kashmir state.

Even trade between historical adversaries with border conflicts like Greece and Turkey, and Iran and Iraq have been growing during last two decades despite their historical unresolved longstanding territorial conflicts. Hence, most of the countries of the world now do not sacrifice their trade interests for the sake of their traditional security interests and longstanding territorial conflicts.

Since August 2019, this is the second time that the Pakistan government has indicated resumption of trade ties with India, but has backtracked. Last time around, on March 31, 2021, federal minister Mr. Hammad Azhar informed the media that the government had decided to allow the import of cotton and sugar from India to meet the shortage of both items, but then the next day, the federal cabinet rejected the proposal and decided to introduce a precondition of no trade with India until “India doesn’t review … the unilateral steps it took,” referring to the revocation of Article 370 in Kashmir.

Before the 1965 India-Pakistan war over Kashmir, India was Pakistan’s largest trading partner, but then formal trade with India was halted, which could never be restored to its past glory. With the launch of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1984, the hopes were that South Asia will also follow the global trend of regionalism like EU and ASEAN countries, which would have ultimately pushed India-Pakistan bilateral trade relations upwards as well.

In 1995, the SAARC Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA) was implemented to improve trade among SAARC member states and then South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) came into force in 2006 to liberalize trade. The trade between India and Pakistan slowly picked up after 2006, but things kept going back and forth as the ebb and flow in bilateral relations between India and Pakistan kept affecting bilateral trade.

India gave Pakistan the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) status in 1996 and in November 2011, the then Information Minister of Pakistan, Ms. Firdos Ashiq Awan had announced the federal cabinet had approved the MFN status for India. But it could never materialize because of political pressure and finally in February 2019, India also revoked Pakistan’s MFN, when in a terrorist attack in Pulwama, Kashmir, 44 Indian soldiers were killed.

Instead of the SAARC influencing India and Pakistan to build stronger economic bonds, the continuous bickering between India and Pakistan has rendered SAARC dysfunctional. Since 2016, even the biannual SAARC summit have not been held, because it is Pakistan’s turn to organize the SAARC summit and the Indian government is unwilling to attend a SAARC summit in Pakistan. Hence, SAARC is literally dead now as no development has been reported in the last nine years or so.

Pakistan must learn from its all-weather friend, China, which never allows its traditional security concerns to mar its transnational trade with its adversaries. China’s trade relations with both the USA and India are indicative of this approach.

Whenever the question of opening or easing trade with India is raised in Pakistan, either hawkish elements raise the issue of the Kashmir conflict, dominated by the traditional security paradigm where no cooperation is possible with the enemy, or some others raise the issue of trade imbalance in favour of bigger India, motivated by the traditional security principle of relative gains. This explains why twice now the government of Pakistan contemplated resuming trade with India, but then under pressure, abandoned the idea.

Not only the people of Pakistan and India, but the entire South Asian region is expected to benefit from the free trade arrangements between India and Pakistan, but all these potential benefits are sacrificed in the name of traditional security considerations, which are no longer given precedence over transnational trade relations by any other state.

Pakistan must learn from its all-weather friend, China, which never allows its traditional security concerns to mar its transnational trade with its adversaries. China’s trade relations with both the USA and India are indicative of this approach. Pakistan must learn from China how to conduct both trade, and to navigate conflict smartly. For continuing transnational trade with India and improving regional connectivity, Pakistan does not need to sacrifice her principled stance on Kashmir.

Rather, Pakistan needs to delink transnational trade from the Kashmir conflict and keep fighting a diplomatic and legal battle for Kashmir at all forums available to it. The strategic planners of Pakistan foreign policy must realise than an economically more prosperous Pakistan shall be in a better position to do something for the Kashmir cause as compared to an economically weak and infirm Pakistan.