Click here for the previous entry in this series

One of the most precious historical artefacts of Lahore is the Mughal-cum-Sikh complex on the northern side of the walled city. It comprises the Alamgiri or Badshahi Mosque, the Shahi Qila, Shaheedi Gurdwara, Ranjit Singh’s Samadhi, Hazoori Bagh, the marble Baradari, the Tomb of Sir Sikander Hayat and the Mausoleum of Allama Iqbal. The complex has a perimeter of 2.38 km and an area of about 70 acres, but has more history and heritage compressed in it than all Lahore south of the canal. It attracts more visitors than any other site of historical or cultural heritage in the country.

The story of this grand complex, discounting the poorly recorded pre-Mughal period, begins with Emperor Akbar, who built or rebuilt the Fort, and whose name is borne by the eponymous gate in its eastern wall. This was the only gate in the fort at that time, and conveniently located for a march to Delhi through the Shahi Guzergah (the royal passage) route out of Lahore. Later, when Emperor Jahangir built the Maryam-uz-Zamani Mosque in memory of his mother, Akbari Gate began to be known as the Maseeti Gate, indicating it as the passage from the fort to the mosque.

The sprawling grain market along the eastern city wall and its city gate, both carry the name of the Great Mughal. The tale then passes to his son Emperor Jahangir, who, at the very outset of his reign, ordered the murder of Sikh Guru Arjan Singh for siding with Emperor’s rebellious eldest son, Prince Khusrau. The Guru’s Gurdwara now stands at opposite corner to the Roshnai Gate across the open space. The ill-fated Prince Khusrau was born in this very Fort, where, after his loss in battle to his father on the northern bank of the River Ravi, he was brought in chains to the fort and blinded on the orders of his victorious father. The Guru, who had blessed the rebel prince near Amritsar, was also brought to Lahore, tortured and put to death on the corner of the western wall of the fort, where flowed the then untamed Ravi.

The murder of the Guru, though a political event, would have a profound adverse effect on the future relations between the Sikhs and the Muslims. This was the first incident, in a long list of subsequent violent episodes, where politics and religion intertwined to form an explosive brew and sow the seeds of discord between the two religious communities of the Punjab, who had thus far lived in peace with each other. The site of the Guru’s shahadat would be converted into a Gurdwara in his memory during the Sikh reign.

The bloody events at the beginning of Jahangir’s reign were repeated at the end of his reign. The resulting bloodbath will be covered in a separate article, as part of this series on the complex housing Jahangir’s tomb. The Mughals had a sanguinary proclivity towards familial issues. While most of this blood was shed by stepbrothers, Shah Jahan’s sons proved to be the worst on this score, because they were uterine brothers; all having been born to Mumtaz Mahal, now the chief resident of the Taj Mahal.

When the mosque was inaugurated, the whole site was vacant except for the mosque and the fort. Right ahead to the north, one would have seen, at that long past time, the river Ravi flowing from right to left

Shah Jahan’s recalcitrant son Aurangzeb Alamgir, who had revolted against his father and killed his brothers, nephews and even his own son, built the colossal mosque that is one of the iconic relics of the city of Lahore. It is due to this mosque that Lahore never had a separate Eid-Gah. It is an established fact that superpowers of the day plan and execute their development works on a prodigious scale. Shah Jahan’s buildings are a testament to this aphorism, as are the British development works in Lahore at a much later date. Alamgir’s mosque, variably known as Shahi, Badshahi or Alamgiri, remained the largest of all mosques in the Subcontinent till late. It was commissioned in 1671 and inaugurated two years later, but is still the third largest behind the Jamia Mosque Bahria Town Karachi and Faisal Mosque Islamabad.

The animosity between Muslims and Sikhs took birth during Jahangir’s reign, intensified during Aurangzeb’s fanaticism and reached its peak during Abdali’s bloody looting raids. Resultantly, hatred among the Sikhs for Mughals and Afghans morphed into enmity with Muslims in general. Consequently, when the Sikhs became rulers of Punjab, they extracted heavy revenge, though, on the whole, Ranjit Singh ruled, for that era, with a fair disposition. However, he turned many of the mosques for state use. The Shahi mosque was converted into a stable for horses and camels. Its decorative stones and inlays were pilfered to adorn some of the buildings built by Sikh nobles. Col Goulding of the British Army, stationed in Lahore in the early period of British Punjab, wrote in his book Old Lahore that Ranjit Singh used the mosque as a military store. Goulding says that it sustained damage during an earthquake in 1840 and that its minarets were used to fire light artillery guns during the Sikh civil wars in early 1840s. He added that the Mosque was used by the British Army for seventeen years before being restored to the Muslims in 1856. It remained in a dilapidated condition till it was renovated by Sir Sikandar Hayat when he became premier of the province in 1937.

During Sikh rule, a channel of the Ravi flowed along the northern walls of the Fort and the Mosque, as depicted on a signboard displayed near the Roshnai Gate and as recorded in several written records. The northern walls of the Fort and the Mosque were laid during the Mughal era in the 16th and 17th centuries along the course of the Ravi. This is confirmed by that fact that looking out the northern windows of the fort and the mosque, the ground is even now tens of feet below. In my childhood and youth about half a century ago, this depth seemed abysmal at being over fifty feet. Now, however, during my visit there about four years ago, the drop didn’t seem too deep. This is the result of extensive development work over the years, carpeting and re-carpeting of the surrounding roads and the extended landscaping undertaken for the Greater Iqbal Park. The main entrance to the complex in the preceding centuries was through the Roshnai Gate, which, as mentioned in the first article of this series, was lighted at night for the ease of dignitaries visiting the royals in the Fort.

Roshnai Gate is the site of murder of Prince Nau Nihal Singh, the grandson of Ranjit Singh. On 5 November 1840, when the prince was returning after performing the final rites of his father Maharaja Kharak Singh, the successor to Ranjit Singh, a block of stone fell from the gate roof and mortally injured him. The conspirators of this murder couldn’t be identified. His close companion Udham Singh, son of Sikh Prime Minister Dhian Singh, and a younger brother of Heera Singh, also died in this same attack. Heera Singh, who too was murdered, would take his father’s place as Prime Minister and go on to build Heera Mandi – a grain market to start with, but which later gained worldwide notoriety as a red light district. Dhian Singh is the elder brother of Gulab Singh Dogra, who was granted the state of Kashmir by the British on payment of seventy five lakh (7.5 million) rupees.

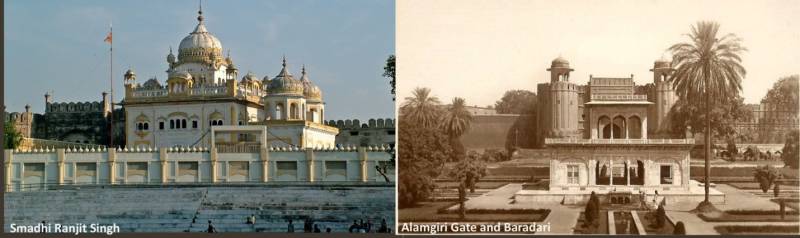

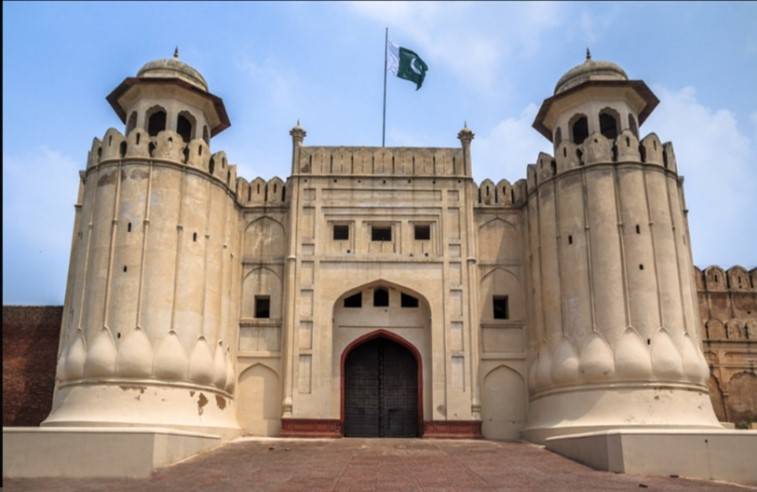

This author has passed through the Roshnai Gate scores of times; the last time with his wife, children and grandchildren. We went all together to experience the grandeur of the architectural complex and to feel the power of the five-hundred-year-long history of the site. Entering through this Gate, one is amazed at the sheer grandeur of the view. Right in front stands the graceful white marbled baradari, arguably the only architectural grace of the Sikh era. On the right is the long and high western wall of the Fort, with the imposing Alamgiri Gate in its centre. The road along this wall slopes all the way along the fort to the old course of the Ravi, that was included in later years as part of the circular road around the city.

The Mughals had a penchant for constructing their grand buildings along water bodies. Shah Jahan built his fort in Delhi along the Yamuna and his Taj Mahal on the left bank of the same river at Agra. Prince Kamran, son of Babur, built his pavilion along the western bank of the Ravi opposite Lahore, which now lies mid-river due to a change in the river’s course. Akbar built his new capital named Fatehpur Sikri around a lake, but the lake dried up after two decades of drawing water on a large scale, forcing the abandonment of the city. Salim Suri Fort, north of the Red Fort, is also constructed on the left bank of the Yamuna. Jahangir’s tomb complex lies along the right bank of the Ravi in Shahdara town. Humayun’s grand tomb in Delhi is near the Yamuna River.

On the further corner across the Hazuri Bagh stand two of the Sikh-era monuments. One, on the far side along the road, as mentioned above, is Gurdwara Dera Sahib that Ranjit Singh built in memory of the Shaheed Guru on the site of his execution. Next to it, nearer the Mosque though well separated, is the elegant, multi-domed, white-and-gold building of the Samadhi of Ranjit Singh.

Ranjit Singh died on 27 June 1839, exactly forty years after he had entered Lahore at the head of his triumphant army. He was cremated between the Badshahi Mosque and the Gurdwara Dera Sahib, where his samadhi stands containing the lotus shaped marble urn of his ashes. There are smaller urns containing the ashes of his four wives and seven concubines who committed satti. In addition, there are two knobs in honour of two pigeons that fell down in the flames, having flown over the funeral pyre (SM Latif, pp 121).

The construction of the Samadhi was started by Kharak Singh, Ranjit’s son and successor, and finished nine years later in the reign of the last Sikh Maharaja Duleep Singh, an eleven-year-old child when he was proclaimed ruler under British primacy. The construction finished just in time, because soon thereafter, the British added the state as a province to their Indian empire. These nine years of internecine bloodshed had witnessed the rule of five Maharajas and the regency of two dowager queens.

On the left of the entrance, a little distance away from the gate, lies the mosque. Between the Mosque and the Fort is a large park. When the mosque was inaugurated, the whole site was vacant except for the mosque and the fort. Right ahead to the north, one would have seen, at that long past time, the river Ravi flowing from right to left. Till before the most recent development work of the Iqbal Park in 2015, the road from the Alamgiri Gate to the Park sloped quite a bit, but has now largely tapered off to a difference in elevation of about 20 feet due to massive carpeting of the roads.

The Fort-Mosque complex is a national heritage of Pakistan. It is a legacy of our ancestors that we have to preserve and then hand over to new generation. We, in Pakistan, have been very negligent about preserving our heritage.

A few years ago, this writer found the Maryam-uz-Zamani mosque opposite the Akbari Gate in a dilapidated condition. Similar is the condition of tomb of Nadira Begum, wife of Prince Dara Shikoh, adjacent to mausoleum of Mian Mir.

We must prove ourselves worthy of our rich and long historical inheritance that spans several thousand years from the ancient Mehargarh, Indus, Bactrian, Kushan and Gandhara cultures to medieval Indic, Sultanate and Sikh eras to modern British and independent times. We have plenty of relics to preserve and be proud of.

Note: The next article will cover the history of the Fort, Hazuri Bagh and the Hazuri Baradari.