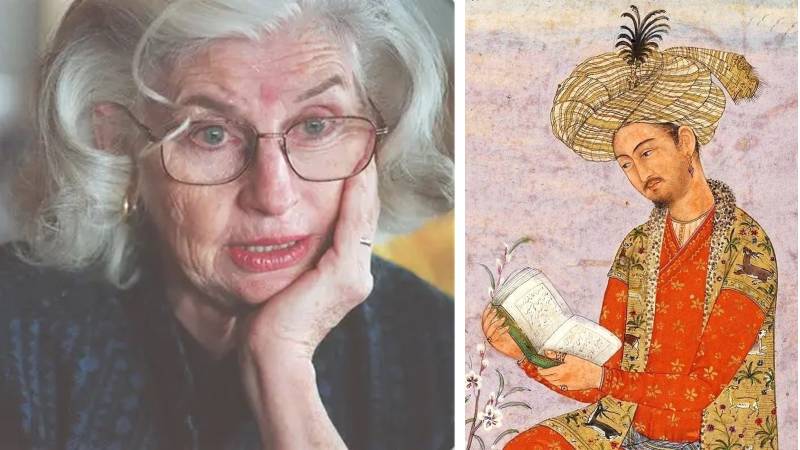

On 7 November 2023, the Washington Post in its obituary section reported the death of Dr Elizabeth Moynihan (94 years), wife of former senator Parick Moynihan. The story was buried among other notices and received little attention. She was much more than the wife of a US senator, although most people may only recognise her as a political strategist, a woman to whom her husband largely owed his electoral success. Elizabeth Moynihan was, however, an eminent historian and scholar in her own right.

Early in her career, a month spent in Rome introduced her to the delights of Italian gardens, and the study of gardens became her lifelong passion. Then later in life, a transformational event occurred. While her husband, Patrick Moynihan, served as a professor at Harvard, he was picked by President Nixon in November 1972 to be the US ambassador to India. The president hoped that he would help heal the rift in the relationship between the two countries, which had soured in the aftermath of the Bangladesh war (1971).

Relocation to India was an unsettling prospect for Elizabeth Moynihan, who had never been there before. At the embassy, she found life stifling, too formal, and protocol-laden and desperately sought some outlet for her interest in architecture and gardens. She had prepared herself for life in India by reading books, mostly about exotic temples and forts, but found nothing related to gardens. However, in her research, she came across a much-acclaimed book published in 1913 by Constance Villiers-Stuart, entitled Gardens of the Great Moghuls. The book was out of print, but it attracted her attention.

A copy of the book, containing an extensive account of the Mughal empire and its founder, Emperor Babur, was sent to her by a friend in London. The author had lived in India as the wife of a colonial officer at the time when the gleaming new capital at New Delhi, planned by Edwin Lutyens, was taking shape. She became a vocal opponent of the introduction in the new capital of bare lawns common in her native England. She authored the scholarly, beautifully illustrated book on Mughal gardens, based on her research.

Stuart’s book extensively described the work and achievements of the Mughal emperor Zaheeruddin Babur (1526-1530), founder of the Mughal dynasty in India. Moynihan was enamoured by this enigmatic ruler and decided to read a translation of his memoir, the Baburnama. The original text of the Baburnama is in Chagatai Turkish, a language now largely extinct. Earlier translations in English – probably what Moynihan had read – were ponderous and difficult to follow. However, a more recent translation by Wheeler Thackston, which includes an erudite introduction by author Salman Rushdie, flows smoothly and is very readable.

In an essay, “An Unplanned Life: In Search of Mughal Gardens,” written years later for the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, Moynihan confessed that it was hard work reading the memoir, as it required ploughing endlessly through unfamiliar names, places, and expressions. She noted “The book is fascinating despite the difficulty in reading it. As the first autobiography in Islamic literature, it gives a rare and vivid account of historic events in little-known areas of the world at the beginning of the sixteenth century.”

Unsurprisingly, Moynihan was not the sole admirer of Babur among intellectuals. The English author EM Forster (1879-1970), best known for his book A Passage to India, was so enthralled by the Baburnama that he always carried a copy of it when he travelled in India. Babur’s son, Humayun, a scholarly man who had built a personal library in Delhi’s old fort, is said to have carried a copy of the book with him in desperate times when he was forced to flee India.

Moynihan was especially fascinated by the description of the gardens that Babur constructed in India. She pursued her interest while in Delhi, and it saved her from the drudgery of endless dinner parties she was supposed to attend or host as an ambassador’s wife. Her fascination with Babur even outlasted the tenure of her husband’s posting in Delhi. After the family returned to the US, she visited India for her archaeological research. Her attachment to Babur occasionally became a subject of humor. At Babur’s 500th birthday celebratory party (born in 1483), her husband Patrick Moynihan raised his glass and proposed a toast to “the other man in my wife’s life” – everyone laughed and understood he was referring to Babur.

In 1978, Moynihan returned to India specifically to search for the lotus garden she had read about in the Baburnama. In 1528, Babur had ordered the building of a foliated octagonal tank and smaller lotus-shaped pounds, at Dholpur, Rajasthan. These were believed to have been lost a long time ago. Moynihan, along with her daughter, travelled from Agra to Dholpur, using Baburnama as a guide. She located remnants of the lotus pool near a village, under a terrace used as a drying platform for cow dung patties by the villagers. Moynihan concluded that in its prime, the garden included a mosque, a pavilion and an aqueduct. Babur loved the place and used it as a country house to get some quiet away from battles and worries of administering an empire.

In the Baburnama, Babur stated that “we suffered from three things in Hindustan. One was the heat, the other the biting wind, and the third the dust”. Of course, a bathhouse has no dust or wind and in the hot weather, it is so cool that one almost feels chill. The lotus garden was one of the several gardens Babur built in India. Moynihan described him as “a natural botanist. He spoke and wrote in several languages. He was a poet. He was a musician.”

Babur’s love for Kabul and dislike for Hindustan are no secret. He survived for only four years after his victory in India. In the Baburnama, he noted “Hindustan is a place of little charm. There is no beauty in its people, no graceful social intercourse, no poetic talent or understanding. There are no good horses, meat, grapes, melons, or other fruit. There is no ice, cold water, good food, or bread in the market.” Babur’s remarks were directed at Indians of all religions.

He had a few nice things to say as well. “Pleasant things of Hindustan are that it is a large country and has masses of gold and silver.” He also liked the Indian rainy season.

Unlike India, Babur loved Kabul, its climate, its fruits and its wines. He even directed that he be buried there. His descendants loved India and made it their home, ultimately, transforming it into the richest and most magnificent country in the world. Lately, Indian Prime Minister Modi and the BJP government have demonised Babur and the whole Mughal dynasty, labelling them as foreigners and occupiers. The fact is that later Mughals, ethnically, through intermarriages, were much more Rajput than Mughal.

If Elizabeth Moynihan were to return to India today, she would be profoundly sad to find her beloved Babur being defamed and his legacy repudiated.