Long before the first Afghan refugees started arriving in Pakistan in the late 1970s, there had been unrestricted movement of people across the AfPak border. For centuries, nomads, for instance, had been moving into the Subcontinent in the winter and returning to Afghanistan in the summer. The unwritten arrangement predated the arrival of the British in the subcontinent, and lasted until 1961, when Pakistan under General Ayub Khan restricted the nomads’ movement. Additionally, for centuries Afghan laborers in the Subcontinent have provided a useful hand to those who were willing to employ them. Although it is almost forgotten today and barely does anyone mention it, Afghan workers, who used their donkeys to move (construction) material around, played an important role in building the canal irrigation system in Punjab under the British in the late 19th centuries. Just like Afghans had opened interior Australia using their camels, they helped build canals and irrigate a large chunk of Punjab using their donkeys.

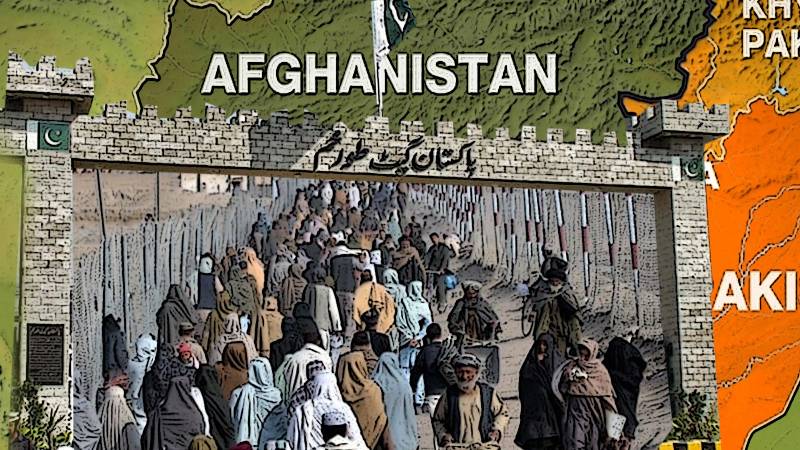

Comparatively speaking, Afghan refugees’ arrival in Pakistan is a recent development (even more recent if one takes into account wave after wave of immigration from and through Afghanistan into the Subcontinent over the last millennium). It is true that almost all Afghan refugees crossed into Pakistan without proper documentation (reasons vary from threat to one’s life to a lack of funds to obtain passport and visa), but to state that the refugees are the first Afghans who entered the Subcontinent without documentation is factually incorrect. Refugees simply followed the routes that had been in existence for centuries. Invaders and conquerors like Mahmud Ghaznavi, Mohammad Ghauri, Zaheeruddin Babur, and Ahmad Shah Durrani — to name a few — did not care much about documentation or permission either. But they are still widely respected in Pakistan despite their being mostly uninvited guests.

Similarly, it should not surprise anyone that a large number of Pakistanis are the descendants of Afghans or those who lived in Afghanistan, as still denoted by their surnames such as Ghauri/Ghori, Ghaznavi, Gardezi, Durrani (including all its branches), Yousufzai, etc.

Fast forward to present time, no one leaves their home unless they really have to. To move to a new place, not knowing what awaits you, is probably one of the toughest decisions one can make, because one has to uproot oneself, and leave behind everything one has: home, family, friends, employment, etc. Wherever a refugee goes, they will have to start and build a new life from scratch.

As someone who has had to start life from scratch a few times so far, I can attest that the last thing one wants in life is to start all over again. Some skills may be transferable from one place to another, but one still must live in a new environment, meet new people, make new friends, and build new connections. This can sometimes be a mentally tough exercise. Afghan refugees are no exception to these issues.

When it comes to Afghan refugees in Pakistan, it is undeniable that Pakistan has hosted millions of Afghan refugees for nearly half a century. There cannot be two opinions about it. During this time, the people of Pakistan have shared their homes, employment places, schools, hospitals, and businesses with Afghan refugees.

There is no doubt in the mind of any Afghan refugee that the people of Pakistan went above and beyond, especially in the initial years of the five-decade long Afghan conflict, to welcome and host Afghan refugees. The reception of Afghan refugees in Pakistan was exceptional at the regional level.

As such, the people of Pakistan have earned the eternal goodwill of the Afghan people. I know many former Afghan refugees who, while unhappy with the Pakistani establishment, still have fond memories of Pakistan and its people, despite leaving Pakistan decades ago. On a personal note, I spent seven years in Karachi, between eight and 15, the formative years in one’s life. Although my family’s economic condition was not ideal at the time, I still consider the seven years I spent in Karachi as some of the best years of my life.

Although AfPak relations experienced ebbs and flows due to Afghanistan’s continued interest in the affairs of Pakistani Pashtuns and its non-recognition of the Durand Line as international border with Pakistan

More than a decade after leaving Pakistan, when I was giving a presentation in the U.S., I surprised my American audience by stating in my opening remarks that I considered Pakistan my second home. I am confident that I am not alone who has this view of Pakistan being my second home.

Realistically speaking, the refugee question is a two-way street. Afghans have received help from Pakistanis when they needed it most. Simultaneously, while helping Afghans, Pakistan has also made an unparalleled long-term strategic investment in Afghanistan through Afghan refugees. The investment will come in handy to Pakistan when an existential crisis strikes. I will provide some historical background to illustrate my point.

The last Afghan King Mohammad Zahir’s family had spent around two decades, between 1880s and 1900s, in northern India. During their stay in India, the family had become acquainted with Indian Muslims and their problems. King Zahir Shah’s family had concluded that should the British decide to leave India, sovereignty in India had to be divided between Muslims and Hindus. There could not be a second solution to the Muslim-Hindu problem in India. Long before the idea of dividing India became attractive to Muslims in India, the Afghan royal family was supportive of it in Kabul.

There were many reasons why Afghans wanted India divided. Religiously, Afghans had centuries-long connection with the Muslims of India, who in turn looked to Afghanistan for support in times of need. Strategically, Afghanistan did not want to share a border with a Hindu majority India. It was too big a country, and there was too much historical baggage attached to it. This did not mean that Afghans hated Hindus. There was a sizeable Hindu population in Afghanistan at the time. Afghanistan just did not feel comfortable to share a border with India due to its size and demographics. The wiser choice was to share a border with a smaller country, and its preferably being Muslim would be cherry on the cake. Pakistan emerged as that smaller (compared to India) Muslim majority country.

Although everyone knows that Afghanistan initially voted against Pakistan’s admission to the UN, few people know or care to know that Afghanistan withdrew its negative vote. Just days after Pakistan’s independence, Zahir Shah had publicly said something about Pakistan which no one cares to remember: ‘When we see India in its present state we feel for our co-religionists. I have sent messages of greetings to both Pakistan and India. Our brothers are Pakistanis, and we will help them even with our blood and with the sword.’

Although AfPak relations experienced ebbs and flows due to Afghanistan’s continued interest in the affairs of Pakistani Pashtuns and its non-recognition of the Durand Line as international border with Pakistan, I am confident had India, instead of Pakistan, become Afghanistan’s neighbour, Indo-Afghan relations would have been much tenser than AfPak relations.

When the 1965 and 1971 Indo-Pak wars broke out, Afghanistan’s royal family, with its good understanding of Hindu-Muslim tensions in the Subcontinent, repeatedly assured Pakistan of security on the AfPak border. As a result, Pakistan moved its troops from the Afghan side of the border to the Indian side, leaving the AfPak border wide open while trusting the Afghans would keep their word of securing the joint border. Not a bullet was fired toward Pakistan from Afghanistan.

At the conclusion of both wars, Pakistani heads of state, Ayub Khan and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto respectively, visited Kabul to personally thank Zahir Shah for his assistance. In the face of these hard historical facts, it is much regrettable when one hears baseless rumours about Afghanistan’s connivance with India to break up Pakistan.

There are certainly better ways to take care of the so-called 1.7 million undocumented Afghan refugees. For instance, can Pakistan register them, and make their stay legal?

Today and in the future, God forbid, if hostilities break out between Pakistan and any other country you can expect the same from Afghanistan. Our minor differences aside, no Afghan would want to see its brotherly Muslim country injured. With this background in mind, Afghans who have spent time in Pakistan and know Pakistan are thus Pakistan’s most reliable long-term investment. They know Pakistan well, like Zahir Shah’s family new the Subcontinent’s Muslims well.

For those who are old enough and remember the 1980s, Afghan refugees were welcome guests in Pakistan. But more than just welcome guests, Afghan refugee camps were fertile grounds for Mujahedin recruitment to fight against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. In other words, many of the male Afghans who entered Pakistan as refugees would re-enter Afghanistan as foot soldiers. The idea was to harass and even possibly defeat the Soviets in Afghanistan so they would not move further south to Pakistan. Slogans like ‘Jihad-i-Afghanistan, difa-i-Pakistan’ were quite common in the 1980s Pakistan. Unlike today, the Pakistan army chief at the time General Zia liked Afghan refugees. There were even rumours that the establishment helped Afghan refugees vote for General Zia in the 1984 referendum. God knows best.

Afghan refugees who do low-skilled work in Pakistan, especially those who are employed by Pakistani employers, are in no position socially and financially to badmouth Pakistan. They are mostly simple and humble people who have moved to Pakistan to live in peace and to earn a decent living. Social media trolls, especially those who comfortably reside in the West, should not be taken seriously. Nor do they represent ordinary Afghans.

It is understandable that priorities change with the passage of time. Pakistan as a sovereign country has the right to admit and expel whoever it wants. It is also evident that out of the four to five million Afghan refugees in Pakistan, a few (or some) of them would be involved in crime. It would be interesting if someone did an academic study on the topic to find out how the ratio of Afghan refugees involved in crime compare to that of the local population. However, to accuse the entire refugee population of being involved in crime and drugs would be untrue and unjust.

That said, there are certainly better ways to take care of the so-called 1.7 million undocumented Afghan refugees. For instance, can Pakistan register them, and make their stay legal? Especially those who have stayed in Pakistan for two decades or longer, today they are more familiar with Pakistan than Afghanistan. To their children, Afghanistan is as alien a place as it is to the average Pakistani. Instead of sending these children back to Afghanistan, should Pakistan not give them citizenship, as they are more Pakistani than Afghan?

Lastly, the idea that Afghan refugees are taking a toll on Pakistan financially does not ring true. Most of the refugees are hardworking people, even if they do petty work. Pakistan’s own population has tripled from 80 million in 1980, when Afghan refugees started arriving in Pakistan, to 240 million today. The presence of a couple million of helpless refugees should pale in comparison to the addition of 160 million people (and counting) to one’s population. Millions of Pakistanis have certainly done a lot for millions of Afghans. Their rich legacy should not be tarnished by rash decisions of a few unelected individuals with no popular mandate from the people of Pakistan.