This year has marked a pause for many – upending routines and leaving people frozen in time. Silence, for me, has been a critical and much needed opportunity to reflect on what has happened and to take stock of what lies ahead. It takes stillness of mind to achieve this.

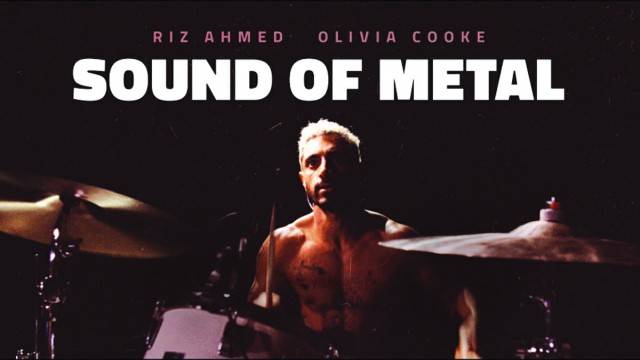

I was made aware of this when watching the recently critically acclaimed move Sound of Metal. Riz Ahmed, a British actor of Pakistani origin, has won his first acting Oscar nomination. He deserves it. His supporting actor Paul Raci has also been recognized for his spell-binding performance. Like any good movie or form of creative art, it is haunting and changes the way one sees life.

The movie is about a young man’s journey through a difficult period. Riz Ahmed plays a heavy metal drummer called Ruben, surviving close to the edge with his partner in a band – and having survived addiction. The story is a strong character narrative: an unusual take on the classic Hollywood hero’s journey. Ruben comes to terms with his hearing loss and his change of life, spending time in a retreat for addicts dealing with auditory loss and learns how to accept deafness as a means of coping with the world rather than a disability.

Without revealing any plot spoilers, it offers some critical lessons on the importance of stillness and silence in our lives. In one pivotal scene, the mentor who runs the facility offers advice: “Just sit in a room and be still. And if you can’t be still, then write until you can.” Sage advice, but hard for many of us to follow. The concept of monkey-mind is real – i.e. we jump like lemurs from thought to thought and are unaware of the cacophony of sounds, experiences and noise that surround us in our daily lives. All too often they drown out our own authentic voice.

Statistics show that nonverbal cues account for nearly 85% of communication. Perhaps that is what makes Riz Ahmed’s performance unique. It is his sheer ability to use his body to communicate. In interviews about the movie, Ahmed revealed that he had spent a year learning about deafness, addictions and drumming to be authentic in character. For me, that was the most powerful aspect of the film – how Riz could convey so much with such an economy of words, his physicality when playing the drums, the frustration and anger when he realises that he is losing his hearing. One is moved by his ability to emote - whether through his soulful eyes or his unease as he deals with the demons of his own past and addictions.

This film is not for the faint-hearted. However, it does yield lessons which are critical in navigating one’s present. The sounds of silence are captured powerfully as one is transported into Ruben’s sonic world – where voices and sounds dull away into vibrations rather than complete silence.

Deafness is not the absence of silence: it marks sonic vibrations that can be dull, just as blind people have told me that blindness is not all black. One still senses colour. This is particularly true for those who have had those senses and then lost them. The closest equivalent is to be the sounds that flow through your body when one is underwater. You can feel that when diving – thirty meters below land and one is suddenly acutely aware of the sounds of your own body – whether the shallowness of one’s breath or the strength of your beating heart while sharks circle overhead.

Sound or the absence of sound is a critical part of the movie and it is no surprise that the French sound designer Nicholas Becker spent over a year before filming began to work with Darius Maker, the director. He studied sonic experiences and had extensive interviews with people like Ruben. The experience of those who have hearing and then lose it are very different from those who have never heard.

It made me wonder about the human experience. Fetuses begin to hear around 18 weeks of pregnancy and by 24 weeks, they hear muffled noises – similar again to the sound of being underwater though resonate with the words spoken with them. They familiarize themselves with their mother’s voice and are soothed by it. Though there is no scientific evidence that listening to Mozart would result in genius, there is evidence based on controlled experiments that babies recognize certain words from the womb. It is almost like an unspoken recognition.

How can the pause – or the silent pause – then mean as much as the spoken word? When introducing his complete works, Harold Pinter aptly described it “There are two silences. One when no word is spoken. The other when perhaps a torrent of language is employed. This speech is speaking of a language trapped inside it.”

There are certain cultures where silence is revered – predominantly Asian ones and Nordic countries. In America and other Anglo-Saxon cultures, silence is regarded as a void which must be filled. It came as news to me that this has been studied over time and with scientific data to back it up – which often explains cultural differences to communication. An English friend revealed to me when speaking to an African friend, he was offended when he kept turning away and looking into the distance, not offering agreement or eye contact. When he raised his frustration, the friend explained simply “But I was listening. I was offering you my ear.”

The physical aspect of listening with intent meant that one turned one’s ear physically to face the speaker – as a sign of respect and honour was part of the local culture rather than eye contract. In Western culture, where eye contact is the norm, it seemed rude.

I realized this subtle distinction when working in Cambodia and other East Asian countries. The pace of conversation was much slower – people waiting to speak and others waiting to offer opinions rather than the American corporate environment that I am used to, which involved frequent interruption as a sign of engagement and attention. In Japan, there is even a cultural concept of “haragei,” which implies that the best communication is not to speak. It is not the art of speaking but the art of the pause which matters – listening with intent, giving oneself time to respond rather than reacting before thoughts have matured.

Though it is easy to equate silence with the absence of words, or a lack of words, it is important to recognize silence as a powerful form of communication. Silence, like many other words, has multiple meanings – it can imply stillness and pause, listening with intent and reflection and in some cases displeasure and resistance. It does not imply disengagement but rather a form of active intervention and thoughtfulness.

One can even relate more with others through silence. One’s nationality is one form of identity but I would argue that the desire for silence is too.

What do you think about silence? Is it comfortable or awkward when there are lapses in conversation? I relate more with the Japanese. I strive for that moment of pause in a day where, as Rumi said, “The quieter you become, the more you can hear.”

And that was the heartbreaking beauty of The Sound of Metal: the character has to experience deafness in order to march to the beat of his own silent drum.

I was made aware of this when watching the recently critically acclaimed move Sound of Metal. Riz Ahmed, a British actor of Pakistani origin, has won his first acting Oscar nomination. He deserves it. His supporting actor Paul Raci has also been recognized for his spell-binding performance. Like any good movie or form of creative art, it is haunting and changes the way one sees life.

The movie is about a young man’s journey through a difficult period. Riz Ahmed plays a heavy metal drummer called Ruben, surviving close to the edge with his partner in a band – and having survived addiction. The story is a strong character narrative: an unusual take on the classic Hollywood hero’s journey. Ruben comes to terms with his hearing loss and his change of life, spending time in a retreat for addicts dealing with auditory loss and learns how to accept deafness as a means of coping with the world rather than a disability.

Without revealing any plot spoilers, it offers some critical lessons on the importance of stillness and silence in our lives. In one pivotal scene, the mentor who runs the facility offers advice: “Just sit in a room and be still. And if you can’t be still, then write until you can.” Sage advice, but hard for many of us to follow. The concept of monkey-mind is real – i.e. we jump like lemurs from thought to thought and are unaware of the cacophony of sounds, experiences and noise that surround us in our daily lives. All too often they drown out our own authentic voice.

Statistics show that nonverbal cues account for nearly 85% of communication. Perhaps that is what makes Riz Ahmed’s performance unique. It is his sheer ability to use his body to communicate. In interviews about the movie, Ahmed revealed that he had spent a year learning about deafness, addictions and drumming to be authentic in character. For me, that was the most powerful aspect of the film – how Riz could convey so much with such an economy of words, his physicality when playing the drums, the frustration and anger when he realises that he is losing his hearing. One is moved by his ability to emote - whether through his soulful eyes or his unease as he deals with the demons of his own past and addictions.

This film is not for the faint-hearted. However, it does yield lessons which are critical in navigating one’s present. The sounds of silence are captured powerfully as one is transported into Ruben’s sonic world – where voices and sounds dull away into vibrations rather than complete silence.

Though it is easy to equate silence with the absence of words, or a lack of words, it is important to recognize silence as a powerful form of communication

Deafness is not the absence of silence: it marks sonic vibrations that can be dull, just as blind people have told me that blindness is not all black. One still senses colour. This is particularly true for those who have had those senses and then lost them. The closest equivalent is to be the sounds that flow through your body when one is underwater. You can feel that when diving – thirty meters below land and one is suddenly acutely aware of the sounds of your own body – whether the shallowness of one’s breath or the strength of your beating heart while sharks circle overhead.

Sound or the absence of sound is a critical part of the movie and it is no surprise that the French sound designer Nicholas Becker spent over a year before filming began to work with Darius Maker, the director. He studied sonic experiences and had extensive interviews with people like Ruben. The experience of those who have hearing and then lose it are very different from those who have never heard.

It made me wonder about the human experience. Fetuses begin to hear around 18 weeks of pregnancy and by 24 weeks, they hear muffled noises – similar again to the sound of being underwater though resonate with the words spoken with them. They familiarize themselves with their mother’s voice and are soothed by it. Though there is no scientific evidence that listening to Mozart would result in genius, there is evidence based on controlled experiments that babies recognize certain words from the womb. It is almost like an unspoken recognition.

How can the pause – or the silent pause – then mean as much as the spoken word? When introducing his complete works, Harold Pinter aptly described it “There are two silences. One when no word is spoken. The other when perhaps a torrent of language is employed. This speech is speaking of a language trapped inside it.”

There are certain cultures where silence is revered – predominantly Asian ones and Nordic countries. In America and other Anglo-Saxon cultures, silence is regarded as a void which must be filled. It came as news to me that this has been studied over time and with scientific data to back it up – which often explains cultural differences to communication. An English friend revealed to me when speaking to an African friend, he was offended when he kept turning away and looking into the distance, not offering agreement or eye contact. When he raised his frustration, the friend explained simply “But I was listening. I was offering you my ear.”

The physical aspect of listening with intent meant that one turned one’s ear physically to face the speaker – as a sign of respect and honour was part of the local culture rather than eye contract. In Western culture, where eye contact is the norm, it seemed rude.

I realized this subtle distinction when working in Cambodia and other East Asian countries. The pace of conversation was much slower – people waiting to speak and others waiting to offer opinions rather than the American corporate environment that I am used to, which involved frequent interruption as a sign of engagement and attention. In Japan, there is even a cultural concept of “haragei,” which implies that the best communication is not to speak. It is not the art of speaking but the art of the pause which matters – listening with intent, giving oneself time to respond rather than reacting before thoughts have matured.

Though it is easy to equate silence with the absence of words, or a lack of words, it is important to recognize silence as a powerful form of communication. Silence, like many other words, has multiple meanings – it can imply stillness and pause, listening with intent and reflection and in some cases displeasure and resistance. It does not imply disengagement but rather a form of active intervention and thoughtfulness.

One can even relate more with others through silence. One’s nationality is one form of identity but I would argue that the desire for silence is too.

What do you think about silence? Is it comfortable or awkward when there are lapses in conversation? I relate more with the Japanese. I strive for that moment of pause in a day where, as Rumi said, “The quieter you become, the more you can hear.”

And that was the heartbreaking beauty of The Sound of Metal: the character has to experience deafness in order to march to the beat of his own silent drum.