Human Rights Day, marked across the world on December 10, is a good occasion to take stock of the human rights situation in Pakistan, particularly during the last one year, and to assess the direction taken by the state and society. The score card is dismal.

First, the National Commission on Human Rights (NCHR), which is an independent body set up under an act of the parliament and has been in place for almost five years, is now dysfunctional as the term of its chairman and members expired over six months ago.

The posts were initially advertised but it appears that the government had second thoughts when it found that the former chairman of the commission, a relatively independent and assertive former chief justice, was also among the candidates. The advertisement was withdrawn and it was stated that fresh applications will be invited again on the basis of another advertisement to be approved by the federal cabinet. When re-advertised, a new condition was inserted in the qualifications required. Anyone above the age of 65 was declared ineligible - a condition that has not been provided in the act of the parliament itself. The parliament, in its wisdom, had not placed any limitation of age on the grounds that such limitation might deprive suitable persons from being selected. As expected, this executive transgression was promptly challenged in courts and the process of selection has come to a halt. Today, the commission is practically dysfunctional while the bureaucracy claims it is not responsible.

Second, the National Commission on Status of Women (NCSW) has also become dysfunctional upon the retirement recently of its chairperson and members. No urgency has been shown to fill the vacuum. Already incapacitated by administrative and financial constraints, the NCSW is also now totally non-existent. There is no statutory body to address issues in rights violations of women.

Third, the Commission for Protection of the Child has not been formed despite legislation made some two years ago and commitments made long ago before the UN. Fourth, the Supreme Court in June 2014 ordered the formation of a commission for the protection of non-Muslim minorities but it has also not been set up. Fifth, students also have been at the receiving end as terrorism charges were slammed against activists of the recent Students Solidarity March.

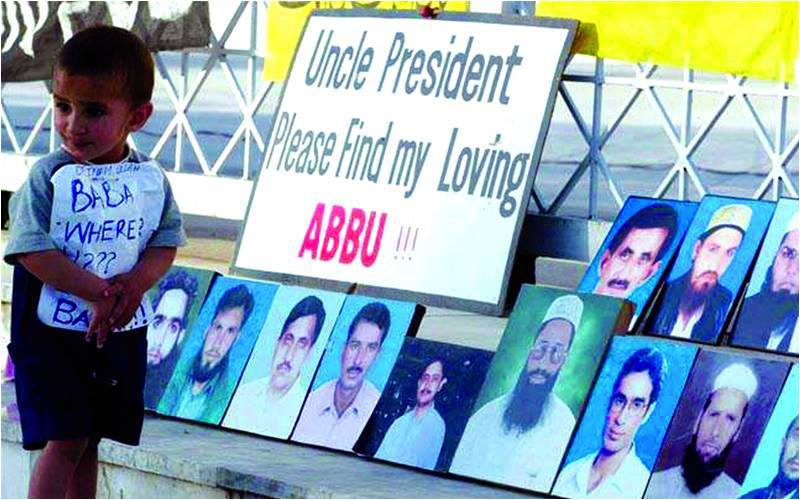

Sixth, despite promises to bring legislation within a month to criminalise enforced disappearances, no law has been made. Complaints of citizens disappearing mysteriously in Balochistan, former tribal areas and other parts of the country not only continue to pour in but have also increased.

Worryingly, women are also now victims of enforced disappearances. Four women in Awaran were recently abducted and disappeared. It was only after widespread protests that they were brought into the open and sent to jail. BNP President Sardar Akhtar Mengal protested and threatened to quit the coalition. Mercifully, on Monday, they were released and a declaration made that no evidence had been found against them. The question why and who abducted them in the first place will perhaps never be answered. At the time of the last budget, dozens of missing persons were recovered after Akhtar Mengal threatened to withdraw from the coalition. No charges were brought against them.

The Commission on Enforced Disappearances claims that it has recovered over 2,000 missing persons during the past few years. That may be true. However, what the commission has failed to answer why has it failed to investigate who the offenders were and why it failed to prosecute them, even though the law under which the commission was formed requires it do so. Are the kidnappers too powerful for the commission or invisible?

Over a year ago, the chairman of the commission disclosed before the Senate Committee that 153 army personnel were found involved in abducting people. The media, which in the words of Imran Khan is “freer than the UK media,” did not report this. Till today no one knows what, if any, action has been taken against those identified by the commission as involved in the crime. When asked in the meeting on August 28, 2018, the chairman of the commission evaded replies.

Seventh, there has also been no progress in legislation on preventing torture and custodial deaths despite the fact that Pakistan is a signatory of conventions against torture and the government’s promises to legislate on this issue. Custodial deaths continue with impunity - the latest being in Rawalpindi on the eve of International Human Rights Day.

Eighth, internment centres were set up in tribal areas during the fight against militancy to keep hard core militants detained pending their trial. These centres have virtually turned into Guantanamo Bay prisons of Pakistan. No information is available about the people kept incommunicado in these centres without access to their families and lawyers. Members of the Senate Human Rights Committee who wanted to visit these centres were not allowed and questions about the status of internees not answered.

When the Peshawar High Court recently declared these centres illegal, the Khyber Pakhtunkhw government responded by issuing an ordinance to set up such centres across the province. During the last hearing in the Supreme Court, the law officer defending the internment centres startled many by stating that most detainees did not have identity cards and were “enemy aliens.” However, Judge Qazi Isa observed that “alien” refers to those who are not citizens of Pakistan. As the matter is before the court, no further comments are warranted.

Human rights are predicated on respecting the rights of others. Is the general apathy towards human rights rooted in the observation that institutions themselves also do not respect each other’s constitutional rights and domains? Over time, this tendency creates a society’s template and becomes its DNA that tolerates trampling of each other’s rights. Respecting the trichotomy of powers as laid down in the constitution is critical.

A thought that haunts today is whether the constitution has been interpreted in such a way that the powers of only one institution, namely the Supreme Court, has been enhanced instead of expanding the independence and powers of all institutions of democracy. I do not know, I really do not want to know!

The writer is a former senator

First, the National Commission on Human Rights (NCHR), which is an independent body set up under an act of the parliament and has been in place for almost five years, is now dysfunctional as the term of its chairman and members expired over six months ago.

The posts were initially advertised but it appears that the government had second thoughts when it found that the former chairman of the commission, a relatively independent and assertive former chief justice, was also among the candidates. The advertisement was withdrawn and it was stated that fresh applications will be invited again on the basis of another advertisement to be approved by the federal cabinet. When re-advertised, a new condition was inserted in the qualifications required. Anyone above the age of 65 was declared ineligible - a condition that has not been provided in the act of the parliament itself. The parliament, in its wisdom, had not placed any limitation of age on the grounds that such limitation might deprive suitable persons from being selected. As expected, this executive transgression was promptly challenged in courts and the process of selection has come to a halt. Today, the commission is practically dysfunctional while the bureaucracy claims it is not responsible.

Second, the National Commission on Status of Women (NCSW) has also become dysfunctional upon the retirement recently of its chairperson and members. No urgency has been shown to fill the vacuum. Already incapacitated by administrative and financial constraints, the NCSW is also now totally non-existent. There is no statutory body to address issues in rights violations of women.

Third, the Commission for Protection of the Child has not been formed despite legislation made some two years ago and commitments made long ago before the UN. Fourth, the Supreme Court in June 2014 ordered the formation of a commission for the protection of non-Muslim minorities but it has also not been set up. Fifth, students also have been at the receiving end as terrorism charges were slammed against activists of the recent Students Solidarity March.

Sixth, despite promises to bring legislation within a month to criminalise enforced disappearances, no law has been made. Complaints of citizens disappearing mysteriously in Balochistan, former tribal areas and other parts of the country not only continue to pour in but have also increased.

Worryingly, women are also now victims of enforced disappearances. Four women in Awaran were recently abducted and disappeared. It was only after widespread protests that they were brought into the open and sent to jail. BNP President Sardar Akhtar Mengal protested and threatened to quit the coalition. Mercifully, on Monday, they were released and a declaration made that no evidence had been found against them. The question why and who abducted them in the first place will perhaps never be answered. At the time of the last budget, dozens of missing persons were recovered after Akhtar Mengal threatened to withdraw from the coalition. No charges were brought against them.

The Commission on Enforced Disappearances claims that it has recovered over 2,000 missing persons during the past few years. That may be true. However, what the commission has failed to answer why has it failed to investigate who the offenders were and why it failed to prosecute them, even though the law under which the commission was formed requires it do so. Are the kidnappers too powerful for the commission or invisible?

Over a year ago, the chairman of the commission disclosed before the Senate Committee that 153 army personnel were found involved in abducting people. The media, which in the words of Imran Khan is “freer than the UK media,” did not report this. Till today no one knows what, if any, action has been taken against those identified by the commission as involved in the crime. When asked in the meeting on August 28, 2018, the chairman of the commission evaded replies.

Seventh, there has also been no progress in legislation on preventing torture and custodial deaths despite the fact that Pakistan is a signatory of conventions against torture and the government’s promises to legislate on this issue. Custodial deaths continue with impunity - the latest being in Rawalpindi on the eve of International Human Rights Day.

Eighth, internment centres were set up in tribal areas during the fight against militancy to keep hard core militants detained pending their trial. These centres have virtually turned into Guantanamo Bay prisons of Pakistan. No information is available about the people kept incommunicado in these centres without access to their families and lawyers. Members of the Senate Human Rights Committee who wanted to visit these centres were not allowed and questions about the status of internees not answered.

When the Peshawar High Court recently declared these centres illegal, the Khyber Pakhtunkhw government responded by issuing an ordinance to set up such centres across the province. During the last hearing in the Supreme Court, the law officer defending the internment centres startled many by stating that most detainees did not have identity cards and were “enemy aliens.” However, Judge Qazi Isa observed that “alien” refers to those who are not citizens of Pakistan. As the matter is before the court, no further comments are warranted.

Human rights are predicated on respecting the rights of others. Is the general apathy towards human rights rooted in the observation that institutions themselves also do not respect each other’s constitutional rights and domains? Over time, this tendency creates a society’s template and becomes its DNA that tolerates trampling of each other’s rights. Respecting the trichotomy of powers as laid down in the constitution is critical.

A thought that haunts today is whether the constitution has been interpreted in such a way that the powers of only one institution, namely the Supreme Court, has been enhanced instead of expanding the independence and powers of all institutions of democracy. I do not know, I really do not want to know!

The writer is a former senator