The Pursuit of Objectivity

Research methodology teaches us that removing one’s prejudices completely from one’s analysis is impossible. This researcher’s handicap takes its toll, in particular, on research related to the social sciences. Even the most seasoned social scientists subconsciously let their biases slip into their research, every now and then. However, the impossibility of attaining it should not encourage researchers to abandon the pursuit of objectivity entirely.

The modern world – or even the medieval or the archaic – is divided into blocs. Liberals, communists, capitalists, democrats, feminists, antifeminists – you name it, we have it. The formation of opinions and the unification of like-minded people is a natural process that cannot – and certainly, should not – be condemned. The problem begins when believers of certain ideologies start branding their beliefs on their work – not subconsciously, but perfectly deliberately.

No “Blocs” in Academia

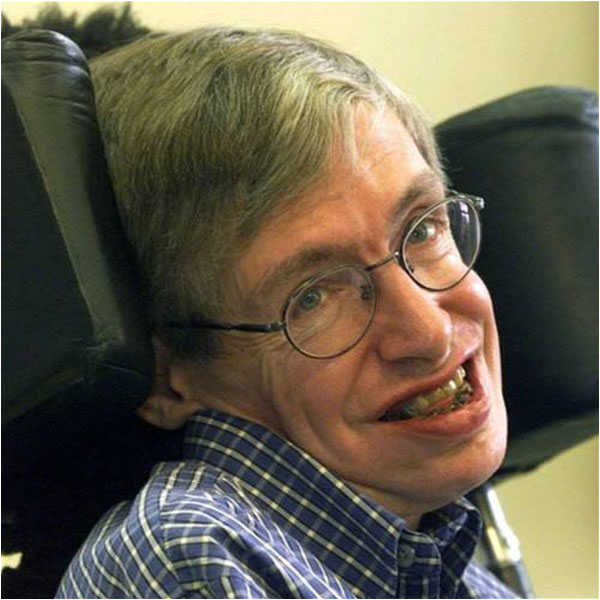

From scientists like Stephen Hawking to historians like Niall Ferguson – both extremely highly esteemed in their respective fields – researchers of all shapes and sizes have, unfortunately, been known to affiliate themselves with ideological schools. Stephen Hawking is a renowned atheist, and his work – centred upon cosmology and physics – frequently debates the existence of God. Given the fact that Hawking’s work saw him study the scientific possibility of the beginning of time, that is neither surprising nor inappropriate. However, for a remarkable scientist, who is against the idea of letting beliefs meddle with research, his atheism takes the limelight ever too often. It wouldn’t be wrong to say that most people know Dr. Hawking more for his religious beliefs than for, say, his gravitational singularity theorems.

For another example: Niall Ferguson, husband of well-known ex-Muslim and anti-Islam propagandist, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, is also one to wear his heart on his sleeve – or his social media profiles, to be more exact. The Scottish historian is repeatedly found sharing such information on his social media pages that paint an ugly picture of Islam. Even a cursory glance at Ferguson’s Twitter account (@nfergus) gives a good idea of which “bloc” he belongs to: a majority of his tweets since the publication of his wife’s book, Heretic (March 24, 2015) highlight how desperately the world needs a reformation in Islam. Whether this activism is out of anti-Islamism or husbandly love, isn’t quite clear. But whatever it is, it isn’t good for academia. It doesn’t befit someone like Niall Ferguson – one of the best financial historians of our time, Lawrence A. Tisch Professor of History at Harvard University, Senior Research Fellow at Jesus College, University of Oxford and Senior Fellow at Hoover Institute, Stanford University – to cherry-pick facts to prove his point. And to pick fights with people who don’t agree with him: Ferguson has often found himself in the middle of public, less-than-friendly arguments with other renowned personalities, like journalist Max Blumenthal, who is a critic of his wife, Hirsi Ali.

What’s next, reject students’ applications if they refuse to acknowledge the necessity of a Hirsi-esque revision of Islam?

Should Researchers be Propagandists?

It is hard to answer this puzzling question judiciously: history is littered with examples of academics who propagated change precisely through the power of their prejudices. And it is also littered with examples of academics whose work lost credibility – precisely through the power of their prejudices. So what is it that researchers ought to do? Influence people into agreeing with their prejudices and losing their work’s credibility; or working objectively and losing the ability to influence people’s ideas?

The power to make this decision, like any other decision, lies wholly with the perpetrator – and so does its responsibility. The researcher must ask himself if his “cause” is more important than his professional reputation. Take Professor Niall Ferguson, for instance.

Professor Ferguson, as already mentioned, has a lot of financial historical research works to his credit, such as The Ascent of Money – a documentary-turned-book – in which he traces the history of money from the Mesopotamian Civilization to modern times. Needless to say, the publication is invaluable, not only to students of finance and history, but also to the general reader, for it has been written really well. Ferguson’s research in The Ascent of Money, and elsewhere, are biblical for many – but only as long as he is perceived to be neutral.

Incidentally, Niall Ferguson’s stance on Islam does not interfere with his capacity as a financial historian, but it does interfere with his profuse political commentary. Everyone who is aware of Ferguson’s allegiance with the “anti-Islamic school” would take all of his political – and, if applicable, financial – opinions with a pinch of salt. But does that matter if his anti-Islamic speech – or tweets, to be more accurate – is gaining more “converts” for his school? It should, if he thinks he is a researcher first and preacher, second.

Use Facts to Arrive at Conclusions – Not the Reverse

The bottom-line of this entire exposition is that researchers – preferably including journalists – need to be more level-headed in their methodology. It is easy to get carried away when one is passionate about a certain subject, be it a cause, a personal preference or religious beliefs. It is certainly easy to be blinded by passion, and to see only that which certifies one’s beliefs. This “blindedness” of sorts is detrimental to the authenticity of research, for a person inflicted by it first arrives at a conclusion then choses and weaves carefully selected facts that support that conclusion – for it must be true, how could it not be?

In the capacity of an honest researcher – if they would like to call themselves that – researchers make a promise of neutrality with their audience – readers, viewers, students – which they should ethically attempt to adhere to. I say “attempt to”, because that really is the best one can do in research that doesn’t concern the physical sciences. And its opposite is the worst.

And, finally, it is not as if the ability to influence people’s ideas is completely lost when one chooses neutrality over propagation; it certainly isn’t. Ideas that are truly backed by facts – and not formed by selecting carefully sifted information that suits your preferred conclusion the best – do not need to be shouted from rooftops to make their mark. They make their place; slowly and steadily, but surely and permanently.

Research methodology teaches us that removing one’s prejudices completely from one’s analysis is impossible. This researcher’s handicap takes its toll, in particular, on research related to the social sciences. Even the most seasoned social scientists subconsciously let their biases slip into their research, every now and then. However, the impossibility of attaining it should not encourage researchers to abandon the pursuit of objectivity entirely.

The modern world – or even the medieval or the archaic – is divided into blocs. Liberals, communists, capitalists, democrats, feminists, antifeminists – you name it, we have it. The formation of opinions and the unification of like-minded people is a natural process that cannot – and certainly, should not – be condemned. The problem begins when believers of certain ideologies start branding their beliefs on their work – not subconsciously, but perfectly deliberately.

Stephen Hawking is better known for his atheism than his field of research

No “Blocs” in Academia

From scientists like Stephen Hawking to historians like Niall Ferguson – both extremely highly esteemed in their respective fields – researchers of all shapes and sizes have, unfortunately, been known to affiliate themselves with ideological schools. Stephen Hawking is a renowned atheist, and his work – centred upon cosmology and physics – frequently debates the existence of God. Given the fact that Hawking’s work saw him study the scientific possibility of the beginning of time, that is neither surprising nor inappropriate. However, for a remarkable scientist, who is against the idea of letting beliefs meddle with research, his atheism takes the limelight ever too often. It wouldn’t be wrong to say that most people know Dr. Hawking more for his religious beliefs than for, say, his gravitational singularity theorems.

Niall Ferguson might be risking his reputation by giving his anti-Islamic stance more prominence

For another example: Niall Ferguson, husband of well-known ex-Muslim and anti-Islam propagandist, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, is also one to wear his heart on his sleeve – or his social media profiles, to be more exact. The Scottish historian is repeatedly found sharing such information on his social media pages that paint an ugly picture of Islam. Even a cursory glance at Ferguson’s Twitter account (@nfergus) gives a good idea of which “bloc” he belongs to: a majority of his tweets since the publication of his wife’s book, Heretic (March 24, 2015) highlight how desperately the world needs a reformation in Islam. Whether this activism is out of anti-Islamism or husbandly love, isn’t quite clear. But whatever it is, it isn’t good for academia. It doesn’t befit someone like Niall Ferguson – one of the best financial historians of our time, Lawrence A. Tisch Professor of History at Harvard University, Senior Research Fellow at Jesus College, University of Oxford and Senior Fellow at Hoover Institute, Stanford University – to cherry-pick facts to prove his point. And to pick fights with people who don’t agree with him: Ferguson has often found himself in the middle of public, less-than-friendly arguments with other renowned personalities, like journalist Max Blumenthal, who is a critic of his wife, Hirsi Ali.

What’s next, reject students’ applications if they refuse to acknowledge the necessity of a Hirsi-esque revision of Islam?

Should Researchers be Propagandists?

It is hard to answer this puzzling question judiciously: history is littered with examples of academics who propagated change precisely through the power of their prejudices. And it is also littered with examples of academics whose work lost credibility – precisely through the power of their prejudices. So what is it that researchers ought to do? Influence people into agreeing with their prejudices and losing their work’s credibility; or working objectively and losing the ability to influence people’s ideas?

The power to make this decision, like any other decision, lies wholly with the perpetrator – and so does its responsibility. The researcher must ask himself if his “cause” is more important than his professional reputation. Take Professor Niall Ferguson, for instance.

Professor Ferguson, as already mentioned, has a lot of financial historical research works to his credit, such as The Ascent of Money – a documentary-turned-book – in which he traces the history of money from the Mesopotamian Civilization to modern times. Needless to say, the publication is invaluable, not only to students of finance and history, but also to the general reader, for it has been written really well. Ferguson’s research in The Ascent of Money, and elsewhere, are biblical for many – but only as long as he is perceived to be neutral.

Incidentally, Niall Ferguson’s stance on Islam does not interfere with his capacity as a financial historian, but it does interfere with his profuse political commentary. Everyone who is aware of Ferguson’s allegiance with the “anti-Islamic school” would take all of his political – and, if applicable, financial – opinions with a pinch of salt. But does that matter if his anti-Islamic speech – or tweets, to be more accurate – is gaining more “converts” for his school? It should, if he thinks he is a researcher first and preacher, second.

Use Facts to Arrive at Conclusions – Not the Reverse

The bottom-line of this entire exposition is that researchers – preferably including journalists – need to be more level-headed in their methodology. It is easy to get carried away when one is passionate about a certain subject, be it a cause, a personal preference or religious beliefs. It is certainly easy to be blinded by passion, and to see only that which certifies one’s beliefs. This “blindedness” of sorts is detrimental to the authenticity of research, for a person inflicted by it first arrives at a conclusion then choses and weaves carefully selected facts that support that conclusion – for it must be true, how could it not be?

In the capacity of an honest researcher – if they would like to call themselves that – researchers make a promise of neutrality with their audience – readers, viewers, students – which they should ethically attempt to adhere to. I say “attempt to”, because that really is the best one can do in research that doesn’t concern the physical sciences. And its opposite is the worst.

And, finally, it is not as if the ability to influence people’s ideas is completely lost when one chooses neutrality over propagation; it certainly isn’t. Ideas that are truly backed by facts – and not formed by selecting carefully sifted information that suits your preferred conclusion the best – do not need to be shouted from rooftops to make their mark. They make their place; slowly and steadily, but surely and permanently.