The Left and Right of Populism

The word ‘populism’ in Pakistan entered the mainstream political discourse rather late in the day. This, despite the fact that the word began to appear with great frequency in discourses, books and articles in the United States and Europe after Donald Trump surprised many political pundits by winning the 2016 US presidential elections; and when right-wing groups campaigning to pull Britain out of the European Union (EU) won a slim (but equally surprising) majority in a June 2016 referendum.

Forms of politics that were once perceived to only be present on the fringes and margins of society, stormed the mainstream. What’s more, the storming took place through conventional democratic means. This put political scientists in the US and the UK on the spot, because they failed to foresee a Trump victory, or a ‘yes’ vote for Britain to leave the EU. Most political scientists and commentators had to confess that they had ignored or undermined certain symptoms which were signalling an unprecedented mood swing taking place within large segments of the polity. Thus began a more serious study of this swing.

The two events were understood as ‘shocks’ because they weren’t about the conventional right-wing winning an election and a referendum in two prominent democracies. The shocks were about an ignored and even ridiculed ‘far-right’ storming the bastions of Western democracy. And that too with the power of the vote, and through means that were entirely constitutional and legitimate. Early studies on Trump’s triumph in the US in 2016 suggested a return of populism, or a performative and ‘emotional’ style of politics which had emerged in bursts in the US since the 19th century, but was never able to grow the legs needed to enter the White House. Political scientists investigating the ‘shocking result’ of the referendum in the UK, too, concluded that the result was symptomatic of populist politics coming to the surface.

These findings then led to the fact that populism was a more widespread phenomenon when far-right politicians and parties in multiple European countries either started to come to power (through democratic means) or witnessed a rapid expansion of their vote-banks. Further studies suggested that populism was enjoying similar gains in South America, Africa and Asia, and that it was emerging from the right as well as the left. But what is populism, really?

The most dominant answers to this question were provided by social and political scientists who have been studying populism long before it became such a buzzword from 2016 onwards. Cas Mudde is one such scholar. He has constantly evolved the meaning of populism. Mudde has closely critiqued a variety of definitions of populism to formulate a set of traits which can best define it, especially in its present form. To Mudde, populism is a ‘thin-centred ideology’ that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups: ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite.’

By this, Mudde means that populism is unlike ‘thick ideologies’ which have fuller centres, such as socialism, Marxism, fascism, liberalism, etc. Therefore, populists are not obligated to follow a fully formed ideology. In fact, populism’s ‘thin centre’ often thickens itself by adopting bits and pieces from other ideologies. These can be contradictory to each other as well. For example, modern-day populists in Europe and the US enthusiastically adopt the social conservatism present in the conventional right-wing parties, but unlike these parties, populists largely oppose the reduction of the state’s role in economic matters. Ironically, in this regard at least, populists in the West are quite like classic social democrats.

There are many similarities between modern-day populism in the West and in the ‘Global South,’ but there are some stark differences as well. Populist manoeuvres and policies of authoritarian regimes and dictators are not our subject of study here. The reason why populism has become such a problematic occurrence today is because it has triggered the electoral emergence of ‘authoritarian-minded’ politicians in both developed as well as developing democracies. But if millions of people have voted for populists in elections in these democracies, why has populism become such a bad word? Was it always explained in this manner? Largely, yes.

If not ‘bad,’ then it was certainly understood as something abnormal which emerges in faltering democracies. The more alarming view in this context was that populism had the potential to mutate and shape a dictatorship built around a cult of personality. These were some of the observations shared by sociologists and political scientists during a conference held in 1967 at the London School of Economics (LSE). After recently reading a ‘verbatim report’ of the conference published by the LSE, I concluded that, while trying to formulate a definition of populism, scholars at the conference were heavily influenced by what had taken place in countries such as Germany, Italy and Spain between the two World Wars.

Many of the scholars at the conference were leaning towards explaining populism as a form of quasi-fascism. But in the end, none of them were quite sure what to make of populism. Nevertheless, this conference went a long way in developing what became to be known as ‘populism studies.’ These evolved slowly at first, but began to accelerate from the early 2000s, hitting a peak of sorts after 2016. There have also been sociologists and political scientists who have challenged the ‘demonisation’ of populism by suggesting that it produces social movements which can make democracies more dynamic, increase people’s participation in them, and usher in much-needed economic and social reforms.

that of social conflicts

(Image Credits: The Borgen Project)

However, the majority of scholars studying populism tend to struggle to be optimistic about populist upsurges. Empirical data suggests that on most occasions, outcomes of populism have been detrimental to democratic institutions and processes.

A consensus of sorts has developed among most sociologists and political scientists in the West about the following traits of populism:

- It is a thinly-centred ideology which borrows from ‘full’ ideologies to style a kind of politics which largely appeals to emotions.

- It can emerge from the right as well as the left.

- It is not a cohesive ideology but more akin to a style, discourse or mode of language.

- It is ‘anti-elite’ and valorises ordinary people.

- It makes grand policy statements but with little follow-through.

- Its vessels are poorly organised and ill-disciplined; a movement more than a party.

- It is often characterised as a specific political style, discourse, frame, or strategy, designed to mobilise the ‘people’ against, allegedly corrupt, conspiring elites and the institutions they occupy.

- In its current form, populism is the outcome of the failures of neoliberal economics which reduced the economic functions of the state/government, who, in turn, outsourced these functions to big businesses and multinational corporations and then bailed them out during the 2008 global recession.

So, populism is not an ideology per se. It is a style. It doesn’t really have a dedicated doctrine as such. It is mostly shaped by booming rhetoric and chest-thumping antics. It exists on the right as well as on the left. Populism on the left is often referred to as ‘social populism.’ It perceives established left-liberal and/or social democratic parties as compromised entities that do not challenge capitalist hegemonies anymore. Populism on the right is called ‘national populism.’ This strand rejects conventional conservative parties whom it criticises for becoming disconnected with the ‘silent majority’ and for watering down their views on matters of morality.

In the West, social populism is largely an extension of causes of the postmodernist left. Causes such as social justice, minority rights, gender/racial equality, etc. But this nature of left populism has failed to expand its appeal beyond the ‘safe spaces’ it has carved for itself. Before the 1970s, leftist politics was largely based on class conflict. After the Cold War, the politics of class conflict was replaced with that of ‘reformed’ capitalism. Nevertheless, populists on the left in the West did not emerge to revive politics of class conflict, but rather that of social conflicts.

National populism is anti-immigration and pro-nativism. Nativism is linked to an exclusivist nationalism that only considers a particular segment of society as worthy of being a country’s citizens. National populism is also highly suspicious of social populists and often refers to them as ‘neo-Marxists.’ But social populism has only a superficial relationship with Marxism.

The world has been witnessing the shrivelling of the idealistic perception of democracy. It is democracy’s other, less pleasant side that has become more prominent

National populism encourages religion’s role in politics. But in Europe at least, this role is not theocratic in nature. It is more to do with Europe’s Christian heritage. Both left and right populists position themselves as being ‘anti-elite,’ and ‘pro-people’. But populism has little by way of its own political programme to offer. It piggybacks on other more substantive political ideologies. Often, left and right populisms merge inside a single carrier. It is a style in which a leader uses dramatic, albeit contradictory rhetoric, to exhibit himself as a people’s voice against a cold, cruel elite.

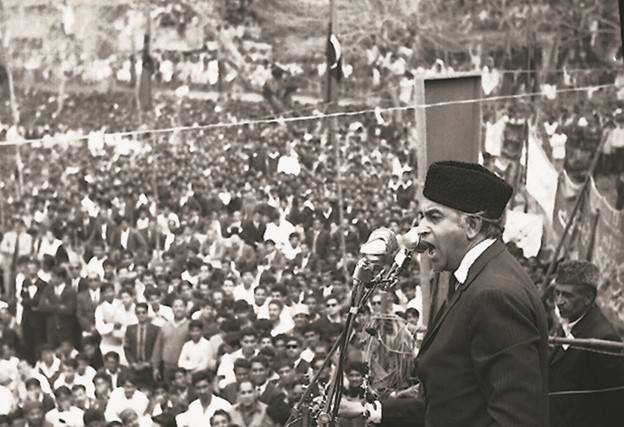

He/she moves back and forth, from left to right (or vice versa) to conjure a narrative that energises his/her supporters. In Pakistan, for example, ZA Bhutto (1971-77) and Imran Khan (2018-2022) often did this. The energy generated in an audience through this back-and-forth rhetoric is absorbed by the populist and becomes an ego-boosting dynamic. This is when the populist claims to have ‘become one with the people.’ Bhutto often claimed this.

claimed that he had become ‘one with the people’

(Image Credits: Dawn)

It Came From Within

Early on, or during the first year of Trump’s presidency, certain political scientists rushed to describe populism as an alien entity that had breached democracy and was eating it from the inside. But as populism continued to expand its electoral appeal, the claim that it was something outside of democracy started to lose traction. Some scholars and academics studying the rise of populism turned to the writings of the British political theorist Margaret Canovan and the sociologist Micheal Mann. In 1999, Canovan wrote that there were two sides of democracy. One is idealistic and the other is pragmatic. Populism arises due to the tensions between the two sides.

In 2005, Mann published The Dark Side of Democracy, in which he argued that democracy (when flexed in the context of majoritarianism) has sometimes produced actions that one often expects from authoritarian regimes. Mann wrote, “Democracy carries the possibility that the majority might tyrannise minorities.” Two examples come to mind: the 1974 ouster of a supposedly ‘heretical’ community from the fold of Islam in Pakistan through an act of an elected parliament, and the demonisation of India’s Muslim citizens by a popularly elected Hindu nationalist government. National populists elected to power in various countries in the 2010s, look to actively marginalise minority groups in a bid to create a more homogeneous national whole.

To Canovan, populism is not something that exists outside democracy—it emerges from within. In their 2013 book Political Religion Beyond Totalitarianism, the historians J Aigusteijin, P Dassen and M Maartje argue that political scholars were slow to grasp ‘the duality of democracy’ because, after the Second World War, democracy was thoroughly romanticised as the opposite of the totalitarianism that had emerged in Russia (Stalinism), Germany (Nazism), Italy (Fascism) and, later, in China (Maoism).

multiculturalism

(Image Credits: BBC News)

Political scientists in the West saw these as ‘political religions’ that were imposed upon the people. Democracy, on the other hand, was posited as a rational, sober and secular idea. However, according to Aigusteijin, Dassen and Maartje, if secular ideas such as nationalism and communism in the mentioned countries were ‘sacralised’ to become political religions, democracy too was deified and sacralised. This is why some staunch democrats in Pakistan while speaking of the possibility of a martial law due the recent tussle between the military establishment and the judiciary often say ‘khudana khwasta’ (God forbid), as if democracy were a sacred doctrine. It is not sacred, but certainly sacralised.

In the 2010s, Hindu nationalists came to power in India and radical right-wing Zionists were elected to power in Israel. During the same period, national populists were elected in various European countries, and in the US. They did not invade democracy from outside to establish ‘electoral authoritarianism’ or ‘illiberal democracy.’ They were part and parcel of a side of democracy that was ignored. Aigusteijin, Dassen and Maartje remind us that the Nazis too were elected and supported by a vast number of Germans.

Although this was later explained away as an act of temporary madness — just as the electoral victories of demagogic populists are being viewed today — this ‘madness’ does not come from outside democracy, but from within it.

What is to be done?

What the world has been witnessing for well over a decade now is the shrivelling of the idealistic perception of democracy. It is democracy’s other, less pleasant side that has become more prominent. This is what political scholars are grappling with.

So, what is to be done? The discourse in established democracies is moving towards introducing certain mechanisms that would regulate democracy’s ‘dark side.’

Paradoxically, this may entail using illiberal tendencies of democracy to safeguard its liberal sides. So, should democratic values such as free speech, inclusiveness, etc, be strictly regulated to mitigate the possibility of illiberal forces entering mainstream politics? Wouldn’t such acts contradict the whole idea of liberal democracy?

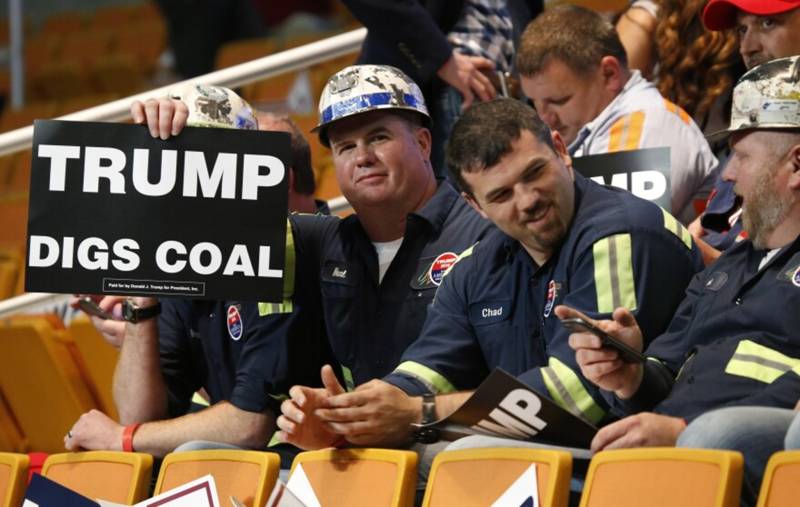

(Image credits: West Virginia Public Broadcasting)

According to Cas Mudde, populist or illiberal forces that come to power through a democratic process are the result of a contradiction in democracy. Indeed, liberal democracy celebrates the protection of various civil rights, but it also encourages the rule of the majority. The problem arises when this majority consents to undo the rights that democracy provides.

The surprising bit in this is that unlike the conventional right-wing in the West, which had encouraged the reduction of the state’s role in economic matters, right-wing populism is actually looking to expand the state’s role

Times are now demanding a deeper, sharper and a much less idealistic analysis of democracy. It needs to be regulated in ways that may raise eyebrows among the purists and the idealists, but hasn't democracy already been eating its own tail for almost a decade now? It is naive to continue idealising democracy without critiquing it from some awkward angles.

Political scholars and mainstream parties will need to tacitly reinvigorate democracy’s rational and sober sides that have been overshadowed by its more problematic sides that open a window of opportunity for populism. On many occasions, this has caused some serious political and social ruptures. Sometimes, democracy’s biggest enemy can be democracy itself. Rational regulations will need to be shaped to stop it from eating itself, as it did in Germany in the 1930s, or as it is doing in various countries since the 2010s.

Populism in Asia

The rise of populism or ‘neo-populism’ has been a global phenomenon. Most contemporary political scientists agree that, although populism as we know it today began to rear its head during the mid-1990s, it truly started to become a global occurrence from the late 2000s. To some scholars, it is still peaking. To others, it is declining, but the decline is slow. Most of the discourse on populism is being shaped in the US and Europe. Therefore, many Asian scholars have critiqued their European and American peers for only exploring populism in the context of its rise in the West. Asian scholars investigating populism in their own backyards posit that, although populism in Asian countries shares many traits with the populism that emerged in the West, there are also some significant differences between the two.

However, there is consensus among most scholars that contemporary populism is almost overwhelmingly ‘right-wing’ in nature. Another interesting thing to note is that most populists emerge from the same ‘elite’ groups that they attack. This may be a symptom of intra-class tensions in a society in which serious divisions have developed within economic elites.

My own study of populism continues to exhibit that, whereas in the West, populism largely (but not exclusively) seems to be attracting the support of the working and rural classes, in Asia it has gained more traction among urban and peri-urban middle classes. This may be due to different attitudes towards neoliberal economics in the West and in Asia.

The post-1970s ‘neoliberal’ policies by Western governments — which reduced the economic role of the state — irritated the working classes and parts of middle-income groups. This irritation mutated into becoming anger towards corporate elites. These elites greatly benefitted from neoliberal policies when established political parties in the West began to outsource many aspects of governance to them.

Populists stepped in to navigate the resultant anger to their own advantage. To be heard and seen, they brought to the surface certain ‘politically incorrect’ notions that had been suppressed in the West between the end of the Second World War in 1945 and the end of the Cold War in 1991. What came to the surface was ultra-nationalism, xenophobia, racism, politicised religion, etc. So, to counter ideas such as multiculturalism and globalisation, for example, populists in the West encourage nativism and localism and demand stricter anti-immigration policies.

The surprising bit in this is that unlike the conventional right-wing in the West, which had encouraged the reduction of the state’s role in economic matters, right-wing populism is actually looking to expand the state’s role. This is symptomatic of the belief that the sympathies of the working classes in the West have continued to shift from the left to the populist right.

On the other hand, the middle classes in Asia gladly embraced neoliberalism, which provided them a sense of being freed from state regulations and, thus, accumulate wealth and status on their own terms. But it is not religious nationalism, xenophobia, cult of personality and a growing authoritarianism that is shaping Asian populism. According to the Chinese political scientist Wang Shiru, for decades after World War II, these traits were not part of mainstream politics in most European countries and in the US.

They only began to crawl back to the surface after the Cold War and then, with more force, during the 2010s. Wang and Edward Vickers posit that in Asia, these traits were already deeply embedded in the mainstream politics of the region, especially in countries that emerged during the rapid decolonisation era.

Charismatic leaders built from a cult of personality and championing ultra-nationalism, xenophobia and the politicisation of religion have been appearing in Asia for years. Therefore, much of Asian politics has been inherently populist for decades now. And this brand of politics has appeared from the left as well as the right. Asian populism only intensifies these traits which are already part of mainstream politics in most Asian democracies.

So, in the West, populism is the weapon of the political/economic elites that are out to usurp political power of the ‘old’ faction of the same elites by adopting and utilising the anger and ‘patriotism’ of the apparently the ‘silent majority.’ In Asia, however, it is middle class groups who are intensifying ultra-nationalism and religious nationalism that are already present in the mainstream, to bolster their economic influence with political power — a power that they are trying to snatch from the older factions of the economic elites that they too have now become a part of.

It’s a matter of who best can exploit the populist traits inherent in many mainstream Asian political systems and psyche. The former Pakistani PM Imran Khan excelled in this. Unlike Western democracies which have institutionalised party systems, most Asian democracies are largely driven by politics based on patron-client relationship. The leadership of the parties is heavily centralised, even to the point of creating a cult of personality around party chiefs. So, in Pakistan, for example, all major mainstream parties strive to create a cult of personality around their leader. But Khan’s supporters elevated his stature to messianic levels, something ZA Bhutto also enjoyed during the peak of his popularity.

(Image Credits: Reuters)

In Western democracies, populism emerges from (or causes) a rupture between established parties and the electorate to create an alternative. The alternative continues to disturb the mainstream alignment between the institutionalised parties and the electorate. Therefore, populism in the West is akin to the disruption of the established party system and electoral alignments.

In most Asian democracies, though, populism is when established parties start to experience disintegrative decentralisation (mainly due to their tussles with the establishment) and new power brokers begin to emerge. These are largely shaped by an establishment unhappy with older parties. The new brokers demonise these parties as being corrupt, and for not doing enough to strengthen nationalism, patriotism and a country’s majority religion. In other words, the tension in this regard between established political outfits and populists in Asia is not about who is more democratic, but who is more patriotic and more moral.

As mentioned, even though in the West, populists emerge from economic elite groups that they then go on to attack, this is more so in Asian democracies. Take the example of Prabowo Subianto who was elected Indonesia's president in October 2023. His rants against ruling and economic elites in his country did not drown the fact that he too came from the same elites. He belonged to a wealthy family, and in the 1990s, he was a high-ranking officer in the powerful Indonesian military. He responded to this contradiction by claiming that he was part of a ‘conscious elite’ unlike the ‘greedy elite.’

According to him, since he was part of the elites, he was thus the best man to tackle them. This is something Imran Khan often repeated as well, especially during his tirades against ‘Westernised liberals’ and ‘Western colonialism.’ Khan, who was once very much part of Westernised elites and had spent more time as a cricketer and ‘playboy’ in London than in Lahore, often explained these experiences as an advantage to fight the elites.

Populism as a whole can also be understood as emerging from the frustrations, anger and fears of groups who may not necessarily be in minority (quite the contrary, rather) but feel that they are being ignored by the ruling elites. In the West, such groups often constitute the white working-classes and rural classes — the ‘silent majority’ as former US president Richard Nixon called them. These may develop an inferiority complex when they are compared to the college/university-educated segments. The latter manage to find more economic opportunities and have a better chance of exercising political, economic and social influence.

Populists become ‘the voice’ of the ‘silent majority’ who, apparently, are taken for granted, exploited and even mocked by the ‘liberal elites.’ In most Asian democracies, though, it is usually the middle-classes who feel this way and react against ruling elites who they accuse of only being interested in appeasing working and rural class interests because these classes have more votes than the middle-classes. India, Thailand and Pakistan are examples of this tendency. Sometimes, in certain Asian democracies, all classes belonging to a majority ethnic group turn to populism because historically they haven’t had much economic success compared to a minority group.

For example, according to the Malaysian political scientist Syaza Shukri, the Malay majority of Malaysia, which is Muslim, has developed an ‘inferiority complex’ because the non-Muslim Chinese minority in the country is often viewed as being a more enterprising, hard-working and educated community. Shukri writes that populist Malay politicians often present this as a majority being treated like a minority and its majoritarianism being threatened by minority groups who work closely with economic and political elites.

Another interesting dimension of Asian populism is the rise of show business and sporting celebrities as politicians, or prominent endorsers of populists. The Indian populist PM and Hindu nationalist Narendra Modi likes to surround himself with famous Bollywood stars who, in turn, became his vocal fans and even mouthpieces. Some were even given tickets by Modi’s party to contest elections. In the last two decades, quite a few show business celebrities have been elected in local and national elections in the Philippines through populist strategies.

Understandably, show-business and populism seem to be natural allies.