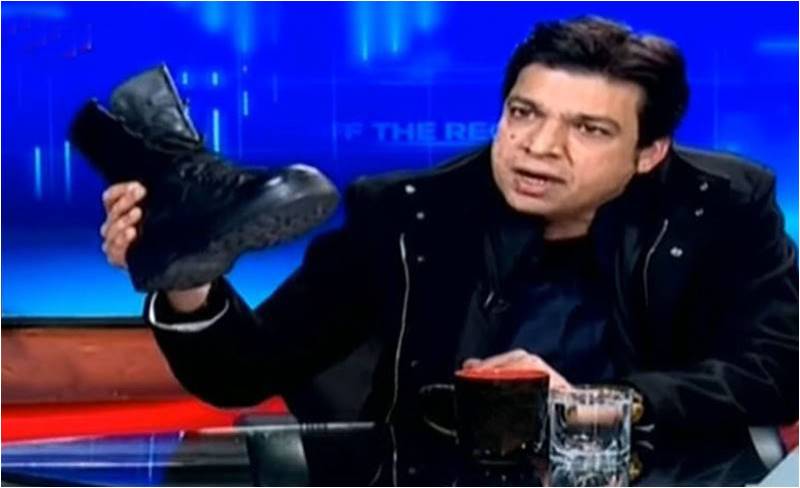

Faisal Vawda of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf is not someone you would normally invite to an evening of polite conversation and good manners. The man is showy and demonstrably shallow and these traits are a matter of record. But on Tuesday evening, while retaining his boorishness, he actually did something cunning: he came to a TV talk show with a boot, the kind worn by soldiers.

His point was simple and his targets were representatives from the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz and the Pakistan Peoples Party. What happened to the bluster, he asked, pulling the boot from under the table and putting it on the table. He was referring to the army chief’s extension debate, opposition’s rhetoric and then falling in line like the lemmings and obediently falling off the cliff one after another.

If he were familiar with T S Eliot, a near-impossibility given Vawda’s impeccable credentials as a virgin on all aspects of good taste, he could have referred to hollow, stuffed men that lean together, “headpiece filled with straw.” But he doesn’t, so he brought the boot with him and actually booted the PMLN/PPP reps from that TV debate.

For that transparency, one has to give him full marks. However, he didn’t realise that by doing what he did, he also implicated his own party and its leader. Here’s how.

If we take his argument that the opposition tucked tail and did as directed, we also have to accept that a non-elected power forced them into passing the three bills that set a higher retirement age for the chiefs of the Pakistani army, navy and air force and allows the prime minister to extend their terms in his discretion.

If so, then despite Vawda’s hemming and hawing about his own party being different, it follows that the PTI is being guided by that same non-elected power and is in fact complicit in furthering that power’s institutional interests: a quid for the quo of surviving in the driver’s seat.

It is here that Vawda’s boot boomeranged on him. Word has it that the boots (plural) aren’t particularly amused by Vawda’s antics. That makes sense. The military’s entire play, notwithstanding its relational dominance, is to put up a facade of civilian supremacy, pay lip-service to the constitution and work the system from the shadows. Granted, its manipulations and machinations are the worst-kept secrets in the realm. But it is one thing to play the game with a degree of plausible deniability and quite another for a federal minister to come and take everyone’s pants off on primetime TV – along with his own – just because he wanted to make a point against the opposition.

If Vawda knew any military history, he would have known that the tactical brilliance of the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour was a terrible strategic mistake since it actively pulled the United States into the Pacific War. Vawda would also know then that the US took out Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of that attack, during Op Vengeance.

But let’s get to the main point here. Consider.

One, the argument that this is the third civilian government and that this republic has arrived at a constitutional succession principle might not be dead but it’s definitely in intensive care.

Two, it is clear that the army has understood the significance of Liddell Hart’s strategy of the indirect approach. As Dr Ayesha Jalal said in an interview, “Power in Pakistan does not flow from any constitutional amendment but from the actual functioning balance between elected and non-elected institutions.” That balance remains in favour of the army even as it now exercises power indirectly and through its civilian proxies.

Three, this means that our framework for analysis must be revisited. It is not just about what’s written in the constitution, but what’s de facto; also, as we have seen with the extension bills and the reversal on General Pervez Musharraf’s treason case, the constitution can be reworked and courts can be prevailed upon. That is the real nature of power.

Four, there’s a Catch-22 here: the army’s strength flows relative to the weakness of political parties and other institutions, but the weakness of other institutions is owed to the strength of the army. To quote Joseph Heller’s classic:

“Orr was crazy and could be grounded. All he had to do was ask; and as soon as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he were sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to, but if he didn’t want to he was sane and had to.”

Five, the only incremental way to escape this conundrum is for the political parties to evolve differently and behave differently. But that’s almost impossible because their evolution and performance is hampered by certain structural constraints. How do they break out of those constraints, especially when it is also in the army’s institutional interest to keep them weak?

In International Relations theory, the Constructivists (especially Alexander Wendt) tried to work the problem between “‘structure’ (anarchy and the distribution of power) and ‘process’ (interaction and learning)” but it hasn’t worked out so far. We face the same problem here, between structure and process.

That said, change being the only permanence, the conversation has begun. Given the power dynamic, it is a necessary though not sufficient condition for rebalancing and reconfiguring the power relations. One cannot give a timeline on this, but it has to resolve itself in one of two ways: a gradual correction or a major disruption.

The first will be a long haul; the second, given the neighbourhood in which we live, an unfortunate event. For now, our world has ended not with a bang but with a whimper. Darwin be praised.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider

His point was simple and his targets were representatives from the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz and the Pakistan Peoples Party. What happened to the bluster, he asked, pulling the boot from under the table and putting it on the table. He was referring to the army chief’s extension debate, opposition’s rhetoric and then falling in line like the lemmings and obediently falling off the cliff one after another.

If he were familiar with T S Eliot, a near-impossibility given Vawda’s impeccable credentials as a virgin on all aspects of good taste, he could have referred to hollow, stuffed men that lean together, “headpiece filled with straw.” But he doesn’t, so he brought the boot with him and actually booted the PMLN/PPP reps from that TV debate.

For that transparency, one has to give him full marks. However, he didn’t realise that by doing what he did, he also implicated his own party and its leader. Here’s how.

If we take his argument that the opposition tucked tail and did as directed, we also have to accept that a non-elected power forced them into passing the three bills that set a higher retirement age for the chiefs of the Pakistani army, navy and air force and allows the prime minister to extend their terms in his discretion.

If so, then despite Vawda’s hemming and hawing about his own party being different, it follows that the PTI is being guided by that same non-elected power and is in fact complicit in furthering that power’s institutional interests: a quid for the quo of surviving in the driver’s seat.

It is here that Vawda’s boot boomeranged on him. Word has it that the boots (plural) aren’t particularly amused by Vawda’s antics. That makes sense. The military’s entire play, notwithstanding its relational dominance, is to put up a facade of civilian supremacy, pay lip-service to the constitution and work the system from the shadows. Granted, its manipulations and machinations are the worst-kept secrets in the realm. But it is one thing to play the game with a degree of plausible deniability and quite another for a federal minister to come and take everyone’s pants off on primetime TV – along with his own – just because he wanted to make a point against the opposition.

If Vawda knew any military history, he would have known that the tactical brilliance of the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour was a terrible strategic mistake since it actively pulled the United States into the Pacific War. Vawda would also know then that the US took out Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of that attack, during Op Vengeance.

But let’s get to the main point here. Consider.

One, the argument that this is the third civilian government and that this republic has arrived at a constitutional succession principle might not be dead but it’s definitely in intensive care.

Two, it is clear that the army has understood the significance of Liddell Hart’s strategy of the indirect approach. As Dr Ayesha Jalal said in an interview, “Power in Pakistan does not flow from any constitutional amendment but from the actual functioning balance between elected and non-elected institutions.” That balance remains in favour of the army even as it now exercises power indirectly and through its civilian proxies.

Three, this means that our framework for analysis must be revisited. It is not just about what’s written in the constitution, but what’s de facto; also, as we have seen with the extension bills and the reversal on General Pervez Musharraf’s treason case, the constitution can be reworked and courts can be prevailed upon. That is the real nature of power.

Four, there’s a Catch-22 here: the army’s strength flows relative to the weakness of political parties and other institutions, but the weakness of other institutions is owed to the strength of the army. To quote Joseph Heller’s classic:

“Orr was crazy and could be grounded. All he had to do was ask; and as soon as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he were sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to, but if he didn’t want to he was sane and had to.”

Five, the only incremental way to escape this conundrum is for the political parties to evolve differently and behave differently. But that’s almost impossible because their evolution and performance is hampered by certain structural constraints. How do they break out of those constraints, especially when it is also in the army’s institutional interest to keep them weak?

In International Relations theory, the Constructivists (especially Alexander Wendt) tried to work the problem between “‘structure’ (anarchy and the distribution of power) and ‘process’ (interaction and learning)” but it hasn’t worked out so far. We face the same problem here, between structure and process.

That said, change being the only permanence, the conversation has begun. Given the power dynamic, it is a necessary though not sufficient condition for rebalancing and reconfiguring the power relations. One cannot give a timeline on this, but it has to resolve itself in one of two ways: a gradual correction or a major disruption.

The first will be a long haul; the second, given the neighbourhood in which we live, an unfortunate event. For now, our world has ended not with a bang but with a whimper. Darwin be praised.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider