Title: The Kalhoras of Sindh: History, Nobility and Tomb Architecture

Author: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Publisher: Dr N.A Baloch Institute of Heritage Research,Jamshoro, Culture, Tourism, Antiquities and Archives Department, Government of Sindh

Price: Rs. 2,000/-

Year: 2024

Publishing a book with a renowned publisher is always a promising sign. However, in the case of this particular book, there is an added layer of significance. Dr Nabi Bux Baloch, the esteemed scholar in whose honour the Dr NA Baloch Institute of Heritage Research was established, and he and the author of this book share common interests regarding Sindh’s history and heritage.

The book under review is more than just a scholarly endeavour; it is a testament to the passion and expertise of Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro. Now, let us dip into the book itself. It is divided into five chapters. As we crack open the cover, we step into a vibrant world where history, culture, and society converge in captivating ways. This is not an academic tome; it is a crafted portrayal by an author who not only possesses academic acumen but also brings firsthand experience and fieldwork expertise before readers.

The first chapter unpacks the Kalhora dynasty unpacks dynamics of power, spirituality, and conflict that shaped the history of Sindh during the Mughal era. Additionally, it explores theories about the originality of the Kalhoras. The narrative of the Kalhoras finds its roots in the accounts of Mian Odhano, whose migration from Arabia to Makran laid the groundwork for the tribe’s lineage.

Jam Channey Khan, a pivotal figure in Kalhora history, navigated the political landscape of his time, forging alliances and establishing the foundations of Kalhora authority. However, after Jam Channey Khan's death, the Kalhora tribe plunged into a period of succession disputes, with his sons Muhammad Mehdi and Muhammad Daud vying for control.

This internal strife led to the fragmentation of the tribe, with Muhammad Daud's descendants eventually founding the state of Bahawalpur, while Muhammad Ibrahim's progeny continued the Kalhora legacy. However, one of the dominant aspects of the Kolhora reign is the initiation of a religious-political popular upsurge called the Mianwal movement. It flourished under the guidance of Mian Nasir Muhammad Kalhoro.

The Mianwal movement grew despite facing resistance from Mughal authorities. The movement was based on some administrative structures and religious mechanisms. The movement’s headquarters was at Garhi in Sindh. The approach/Tariqa introduced some signs, symbols and rituals. Soon, an advisory council or Shahi Group was formed. It comprised eminent and close disciples of Mian Nasir Muhammad, who were bestowed the prestigious title of Shah. Each Shah attained the prestigious position of being the head of the daira. Under his authority were several disciples who were called Faqirs. Disciples, both Shah and Faqir, were to form communities upholding the thought and ideology of their mentor Mian Nasir Muhammad Kalhoro.

During battles, members of advisory councils were called to discuss the situation. In that situation, they were also supposed to protect the land and life of the people falling under their jurisdictions. This group also had a military wing to cope with the growing influence and power of their enemy in their respective dominions, which were called Sariwal and the Sarfarosh respectively. The Sariwal Group included the disciples who worked under the command of other chief disciples of Mian Nasir Muhammad Kalhoro. They were the disciples who were better trained to ambush the enemy camps. The term loreyoon refers to an attack on the enemy property, be they cattle or the village. Another group was the Sarfarosh group. It comprised the best fighters who used their swordsmanship in battles and fought against the Mughals and their supporters.

The movement was also supported through some rituals, four of these being the most significant: Allah Tohar, Du'a, Aazi, and Guftar. Allah Tohar became the slogan of the Mianwal Tariqa. Du'a suggests that after Allah and Nabi (PBUH), Mian was revered. But another Du'a was recited by the disciples. These were the words: “Khathi Bachi Da Kher” (All good for Khathi and Bachi). Khathi (Shawls) and Bachi (turbans) were the symbols of the Mianwal disciples. However, Aaazi was to be recited ceremoniously by the more pious Faqir of the tariqa. Then there is Guftar or a praiseworthy narration. This was an important ritual of the Mianwal Tariqa. The Khathi was a symbol of Mian's authority, and Bachi was the type of turban worn by members of the movement. Khushi was the fine imposed for violating any rule under the tariqa, or committing aggression, crime, or sin, and there was Shadmana; it was ceremonial rejoicing by the Faqirs on Mian Nasir Muhammad Kalhoro's visit.

Whenever Mian Nasir Muhammad Kalhoro visited the daira of any of his Faqirs, there was a resort to Music (Raag). Usually, Surando was played while performing the zikr ritual. The Zikr ritual was also central to the Mianwal Tariqa. No doubt, the ill-fated attempts of Mian Abdul Nabi Kalhoro to challenge Mir Bijar Khan Talpur marked the final chapter in the Kalhora saga, as external interventions sealed the dynasty's fate in 1783. But we should not forget that the Kalhora dynasty epitomises the complexities of power, spirituality, and conflict in the annals of Sindh’s history.

Chapters 2 and 3 discuss in detail the nobility of those times, their status, and role in the Kalhora Kingdom. Both chapters also show who was who in those times in Sindh. The author has mentioned their areas as well as their official positions in political administration. Interestingly, the author, through architecture, has unpacked the political economy, its sources, and geographical areas. There are detailed accounts of the prominent tribes and individuals associated with the Kalhora dynasty. Some of the important tribes were Khuhawar, Khokhar, Jhinjhan, Nuhani, Burfat, Khosa, Marris, Chandia, Rodnani, Nizamani, Laghari, Lund, and Lekhi. These tribes’ locations as well as political power and socio-cultural influence show how the Kalhora kingdom was organised and how it operated. The author has constructed the historical narrative through the architecture of those times.

Additionally, he has also mentioned powerful persons or nobles from each tribe, and has stated how they were connected to the political power of those times. He elaborates that Khuhawars held an important position in the Kalhora court, claiming both religious and political roles. The notable figures among Khuhawar were Chakar Khan Khuhawar, who was a disciple and general of Mian Shahal Muhammad Kalhoro. Another brave man from this tribe was Ghazi Khan Khuhawar, known for ambushing enemy camps. Other powerful names from the tribe were Sultan Khan Khuhawar and Mian Gaji Khan Khuhawar.

Likewise, the Khokhar Tribe was also very powerful; its members were soldiers. Prominent persons of this tribe were Chhutal Faqir Khokhar and Bagho Khokhar. Similarly, another military tribe was the Jhinjhan, which produced eminent generals and soldiers serving the Kalhoras, notably Maqsoodo Faqir Jhinjhan and Meeran Shah Jhinjhan. Another tribe that enjoyed political status was the Nuhani tribe. It played a significant role during the Kalhoro dynasty in Sindh, closely associated with the Kalhora rulers and contributing to the region's socio-political landscape.

One of the influential persons during the time of Mian Sarfaraz Muhammad Kalhoro was Umar Yousif. However, in the Kohistan region, the powerful tribe was the Burfat, which wielded considerable influence throughout various dynasties. Notable figures like Malik Pahar Khan Burfat and Malik Izzat Khan Burfat played crucial roles in shaping Sindh’s history. As mentioned in preceding paragraphs, these noble persons resided in different areas of Sindh. Thus, during the time of Mian Nasir Muhammad Kalhoro, Gaji Shah Khoso was a revered figure known for his military prowess and loyalty. Belonging to the Khosa tribe, he played a vital role in battles against the Mughals and rival factions. His shrine, located southwest of Jobi town in Dadu district, serves as a place of pilgrimage for his tribesmen.

Similarly, Marris played a vital role; in this regard, Hajizai Marris played a crucial role in Sindh's socio-political landscape during the Kalhora period. Another tribe was the Rodnani, which also played an important role in Sindh’s politics, particularly during the time of Mian Yar Muhammad Kalhoro. In this regard, Ghanwar Faqir Rodnani’s name comes first. Another prominent figure from this tribe was Shahan Faqir Rodnani, a spiritual leader, with Mai Chaunri Faqirani as his female disciple. Other prominent members from this tribe were Nangar Faqir Rodnani, Shahnani Faqir, Shamrani Faqir, Seerakh Faqir Rodnani, and Golo Faqir Rodnani.

We should not forget that the location of a tribe shares a lot in terms of the tribe's importance. For example, the Nizamani tribe, during the Kalhora period, was stationed in various parts of Sindh. However, some important persons of the tribe during various periods of the Kalhora era were Ismail Faqir Nizamani, who served Mian Yar Muhammad Kalhoro. Another notable figure was Talah Faqir Nizamani, who was an advisor and special friend of Mian Noor Muhammad Kalhoro and was granted a jagir around the Sanghar district. Likewise, other important names of the tribe were Ghulam Husain Nizamani, the Kardar (revenue collector) of Mian Noor Muhammad Kalhoro, and Ghulam Ali Nizamani, a general and amir of Mian Noor Muhammad Kalhoro with four thousand troops under his command.

Other equally important persons were Magan Faqir Nizamani, Tango Faqir Nizamani, Murad Faqir Nizamani, and Qaisar Khan Nizamani. Another important tribe of that time was the Lagharis. Eminent persons belonging to this tribe were Dato Faqir Jalbani Laghari, a revered figure serving under Mian Abdul Nabi Kalhoro. Another significant fact was about the Bahwani Lagharis, revered for their valor and administrative prowess during the Kalhora era. However, Pahar Faqir Laghari, the eldest son of Shah Bahoo Laghari, played a pivotal role in the governance of the region under Mian Yar Muhammad Kalhoro. Another influential and significant person was Pandhi Khan Laghari.

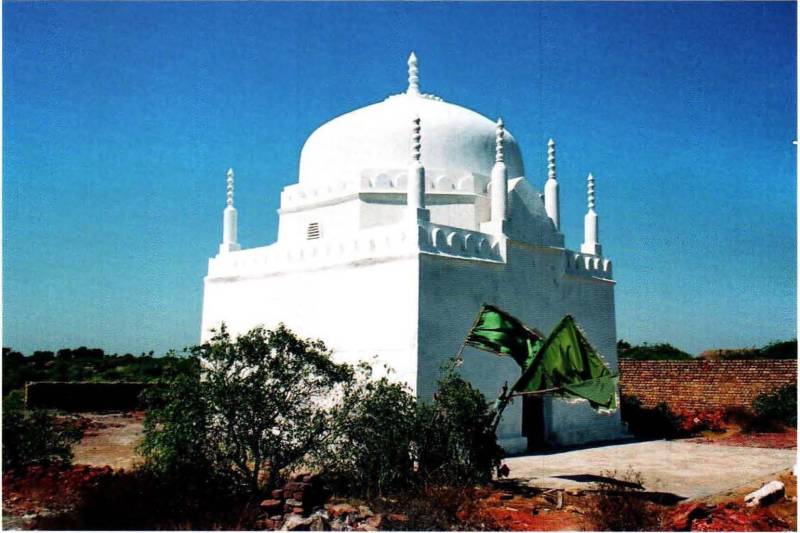

Each tribe, through the Kalhoras’ political and religious organisation, was made bound to play a role in battles and administration. Therefore, it is evident that these tribes were actively involved in military campaigns and administrative duties during the Kalhora dynasty. Most of them served as generals, soldiers, and ministers, contributing to the stability and governance of the Kalhora Kingdom. It is noteworthy that all of them served at different times of the Kalhora Kingdom. Additionally, each tribe has its own burial sites, often located near the shrines of their spiritual leaders or in specific necropolises. The graves and tombs exhibit unique architectural features, shedding light on the rich history and cultural heritage of these tribes and individuals, highlighting their contributions to the region's development and legacy.

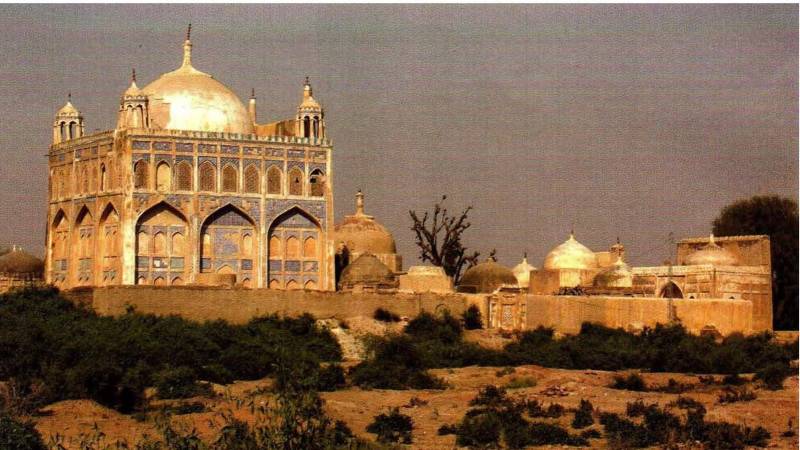

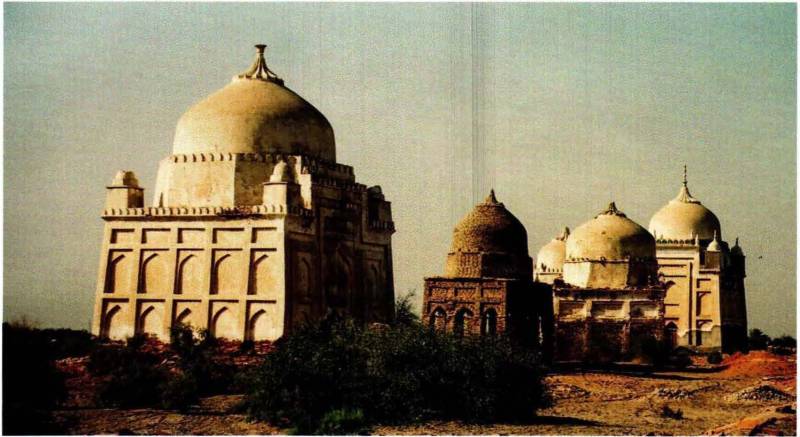

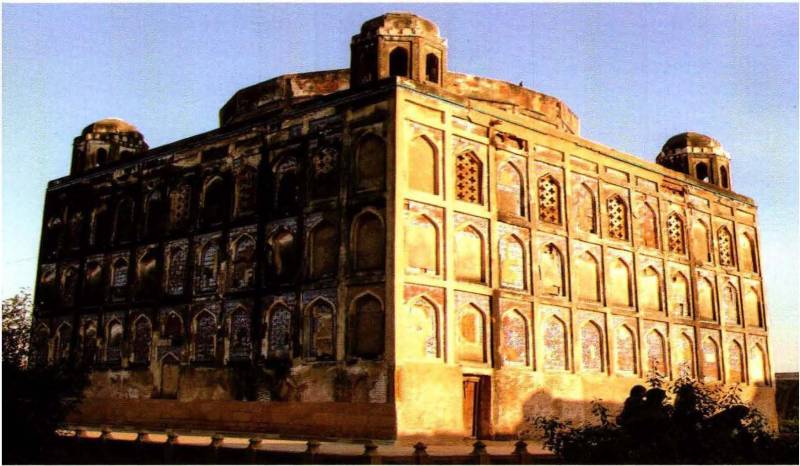

Chapter 4 describes the architectural features of Kalhora period. It explores the architectural elements of buildings. Common structural elements of the dynasty period include squared buildings, with many of the tombs having onion-shaped domes, octagonal drums; structures with glazed tiles, arched entrances, and kiosks crowning the corners of some tombs. Another common architectural aspect is the tomb, typically squared or octagonal in plan, with some featuring exposed brick construction. However, domes in most cases are hemispherical or corbelled, resting on elevated drums, although a considerable number of tombs have domes constructed above them, which can be hemispherical or onion-shaped and are often supported by octagonal or circular drums.

Yet another design element of tombs is that of three-domed structures. Although, canopies are common structures with tombs, often with pillared structures adorned with intricate designs. However, some tombs have ventilators on their domes, allowing airflow and providing natural light to the interior spaces. But, common features include archways, contributing to the grandeur of the structures, and drums and finials - with particularly the finials adding elegance to the architecture.

The decorative aspects include floral motifs, geometric designs, arch motifs, striped patterns, and some tombs exhibit corner pillars rising from the thickness of the walls, a rare feature adding visual interest and complexity. Interior spaces are sometimes decorated with floral motifs and frescoes, although many have suffered damage over time due to neglect and whitewashing.

It should be kept in mind that the nature and usage of a building also condition its shape. In this connection, residential buildings often exhibited architectural elements such as courtyard layouts. These palaces, mansions, and official residences reflect wealth, status, and cultural preferences of the era. The graveyards feature clusters of tombs, while others have rows of graves. The layout and organisation of the graveyard may reflect the historical significance and cultural practices of the community. Additionally, artistic features of Kalhora architecture include paintings, with interiors of the tombs often featuring paintings depicting floral motifs, geometric patterns, folk romances, battle scenes, and everyday life.

Figural depictions are also present in some structures, showcasing painted figural depictions of folk romances, equestrian scenes, and motifs from local tales like Laila-Majnun and Sasui-Punhun. However, some notable characteristics of Kalhora tombs are ornamental lanterns. These lanterns, crafted with intricate detail, add a sense of elegance and beauty to the tombs, showcasing the craftsmanship of artisans. Additionally, elements known as false lanterns also serve as decorative elements on certain tombs, enhancing their aesthetic appeal. Another distinctive feature tombs is the drum upon which the domes rest. Serving as a foundation, these drums contribute to the architectural elegance of the tombs. In addition to that octagonal and sixteen-sided or polygonal designs were also used.

Some tombs also show turrets, adorned with blue tiles, grace the corners of tombs. Other structural elements include ambulatory galleries, rising from the walls of tomb chambers, serving both structural and aesthetic purposes. Intricately integrated staircases facilitate access to the roofs of the tombs.

Some architectural historians are of the view that staircases, intricately integrated into the walls of the tombs, provide access to the roofs, adding to the functionality and accessibility of the structures. These staircases, often overlooked as architectural features, play a crucial role in facilitating maintenance and upkeep of the tombs. However, forts featured sturdy walls, watchtowers, and strategic layouts designed to withstand military attacks and serve as administrative centers.

The book under review mentions that the Kalhora period’s architectural structures have distinctively contributed to the overall grandeur and significance of these historical structures of Sindh. The final chapter sums up how architectural features discussed above have illustrated the richness and diversity of Kalhora period’s architecture.

Join me in extending heartfelt congratulations to Dr Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro, the author of this captivating book, which unravels the intricate tapestry of Sindh's rich history through the lens of Kalhora architecture. The book transports us into an era where humble beginnings blossomed into enduring legacies - of how mere religious mendicants emerged as formidable defenders of their faith and sovereignty under the sagacious leadership of Mian Nasir Muhammad Kalhoro. Indeed, this book offers a multi-layered narrative, weaving together the tales of kings and commoners, nobles and artisans, each contributing to the grand tapestry of Sindh’s heritage.