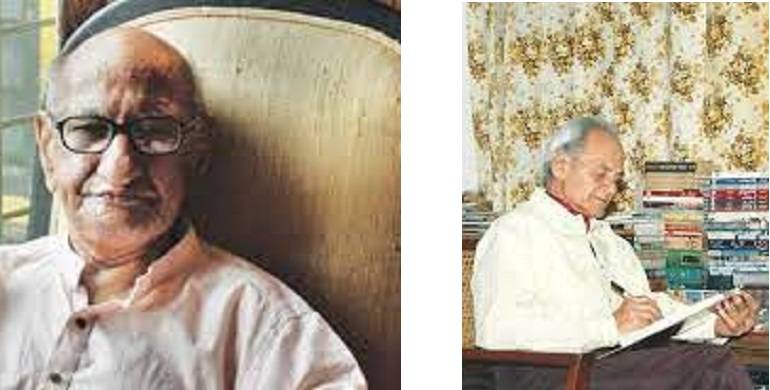

It was great to read a few days ago that the Lahore Arts Council is planning to celebrate the 2019 elevation of Lahore as a UNESCO City of Literature by organising events on the vaunted literary traditions and writers and poets of Lahore, now that the menace of COVID – 19 appears to be waning. A soon as that happens, I believe two of Lahore’s eminent writers who deserve to be remembered as much for their memorable works as for their artistic contributions to the city through their years of long residence are the late Hameed Akhtar and A. Hameed who both passed away 10 years ago this year in quick succession.

Both Akhtar and Hameed shared a lot in common, from their birthplaces in Eastern Punjab to the artistic milieu they eventually inhabited upon their migration to Lahore post-1947, and in the lifelong friendships they cultivated. Akhtar was born in Ludhiana in 1924 and after an initial religious upbringing, quickly distanced himself from having any truck with religion and came under the influence of a gifted group of young poets and writers under the leadership of the soon-to-be-famous Sahir Ludhianvi. These were also the days when he befriended that other young Punjabi who was to become world-famous in the world of Urdu letters as Ibne Insha. In the lead-up to the frenzy of the 1947 Partition, the appalling conditions which Akhtar encountered at the Nakodar refugee camp for three months strengthened in him the lifelong resolve to fight inequality in all its forms and to struggle for the rights of the oppressed.Whereas young Hameed was born in Amritsar in 1928 in a family of wrestlers; his father would even strive to punish him physically to enforce the paternal profession. Hameed’s response was to seek a refuge in his favourite writers. He would later traverse whole swathes of the Indian subcontinent and parts of South-East Asia, which would copiously supply the lush and exotic locales of his romantic stories and novels.

After both the Hameeds had arrived in Lahore, they spent time around the writers and poets there who would later go on to become legendary in their own right. There were the aforementioned Sahir Ludhianvi and Ibne Insha alongwith Fikr Taunsvi, Qateel Shifai, Ahmed Rahi, Arif Abdul Mateen; and occasionally Saadat Hasan Manto. In the cosmopolitan Lahore of those days, differences of faith, caste and ideology would meld into each other and Sahir could still claim the affections of Amrita Pritam, while Qateel could romance Chandrakanta, a Hindu woman who had refused to migrate to India after partition.

Akhtar lived throughout his life without owning a house of his own, while Hameed despite owning a small house in Samanabad, became a virtual recluse in his final days owing to the cold shoulder of both the state and its literary lobbies

However their commonalities end here. For Akhtar had been very active in Communist politics and organizing the Progressive Writers Association (PWA) in Bombay even before partition. In the company of Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Sajjad Zaheer, he had very much become a Party man. But who also found time to dabble in acting; many of the present generation may not know that Akhtar acted successfully in one film in Bombay, which opened the floodgates of the glitzy Bombay film world to him. But unlike many of his Progressive friends who wrote as well as maintained their links with the film world, Akhtar had decided to sever those links and to serve ideology and literature both and came to Lahore.

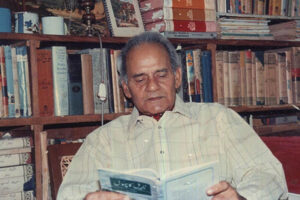

Hameed came under the influence of the great Progressive writer Krishan Chander upon landing in Lahore and was impressed with him enough to write romantic fables and novels based on his myriad travels; so much so that Manto christened him as ‘that blabbermouth who can fall in love even with a lamppost.’ . Interestingly, while he came under the influence of the PWA and hung out with mostly with his friends who were either members of the Communist Party of Pakistan or the PWA, he himself never espoused these ideals in his own writings. The fact that unlike his friend Hameed Akhtar, he was not a Party man meant that he was a full-time writer who churned out mystery and detective novels, columns, pen-sketches and short-stories on an astonishing scale; the tally of his novels goes upto 200. Naturally this meant that he had to compromise on quality over quantity.

As conditions in Lahore worsened in 1949 after the departure of Sahir Ludhianvi and Fikr Taunsvi, Akhtar like many of his other comrades was routinely jailed under the Safety Act. The outcome of one such year-long incarceration in 1951 was the classic Kaal Kothdi (Death Cell). Many regard it as the most significant jail writing from the Indian subcontinent after Maulana Abul Kalam Azad’s Ghubar-e-Khatir (Dust of the Mind). The book shone a much-needed light on the pathetic state of Pakistan’s largely neocolonial prison system in those days and was banned upon publication; however it caused enough consternation among the prison higher-ups in Punjab for them to modify the diet of prisoners and include the book as compulsory reading for would-be jail officers to understand the psychology of prisoners. Though Akhtar also wrote short-stories and was also a translator of no mean accomplishment, it is as the chronicler of the Progressive Writers Movement that he won acclaim and respect, as Intizar Hussain had aptly christened him. Then there are Akhtar’s superb pen-sketches first collected in Ahvaal-e-Dostaan (The State of Friends) and later in an expanded edition as Aashnaiyan Kya Kya (What All Friendships) that are not only an introduction to the sparkling intellect and craft of the man but of those he is writing about. I single out Akhtar’s sketches of the unsung heroes of our literary canon who also died early, namely Ibne Insha and Ibrahim Jalees as well Akhtar’s own modest sketch from among the eleven sketches collected here. Akhtar definitely knew the increasingly rare art of seamlessly melding the writer and his subject and more than sketches they are micro-histories which also document the evolution of the PWA in united India and independent Pakistan.

Hameed influenced at last 3 generations through his writings and columns. One was his own generation; the second was mine because my imagination and the early desire to write were fuelled by his highly-awaited Ambar Naag Maria series in my childhood; and then the millennial generation, for whom he wrote the hit television play Ainak Wala Jin (Bespectacled Genie). While researching my upcoming book on Sahir Ludhianvi and Lahore for Sahir’s birth centenary, I recently rediscovered Hameed’s evocative sketch of Sahir, which is not only an unmatched account of Lahore’s cosmopolitanism in the early 1943-49 years, but also an unforgettable cast of characters, including the two Hameeds, from which their beloved Lahore cannot be separated.

What also distinguished the two Hameeds was that despite the fact that both loved women fiercely, Akhtar was unsuccessful in love, eventually settling for a long and fruitful marriage with a cousin from the family; while Hameed successfully married the love of his life after an affair consummated under various guises and pretexts, now at Lahore’s iconic Kinnaird College where she studied, then at Lawrence Garden, despite the considerable opposition of his family, from which he later disassociated owing to their cold treatment of her.

Despite the varied literary contributions of both Hameeds, the various lobbies of high literateurs that have now become a menace but were still present back in the day did not welcome them in their midst. Akhtar lived throughout his life without owning a house of his own, while Hameed despite owning a small house in Samanabad, became a virtual recluse in his final days owing to the cold shoulder of both the state and its literary lobbies. One can find more about Hameed Akhtar in Ahmad Salim’s sole, definitive biography of the man published while the latter was still living; while Hameed has been well-served by Irfan Javed’s woefully-brief sketch of him in his book of character-sketches titled Darvaze (Doors).

2011 was a difficult year for Pakistan, having lost two of our best and brightest politicians Salmaan Taseer and Shahbaz Bhatti to the bullets of mindless fanatics, followed by the loss of acclaimed television and theatre artiste Moin Akhtar. This was also the year which brought difficult times for Pakistan through the Raymond Davis affair, the Memogate controversy and the killing of Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad. As such, losing such irreplaceable men of letters of the caliber of Hameed and Akhtar one after the other was not only a severe blow to our already stunted cultural life, but more specifically to Lahore, whose intellectual life they enriched with their very presence as well as their writings.

When they passed away, Hameed Akhtar was 87 and A. Hameed was 83. As I write to remember them a decade on after their deaths, I recall Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s couplet which he composed after the deaths, in quick succession, of poets Josh Malihabadi and Firaq Gorakhpuri: “Aik saath aaey aik saath gaey/ Asr-i-haazir ke Mir aur Sauda” [Together they came and together they went/ The Mir and Sauda of our present].

Note from the editors: An earlier version carried an incorrect image of Hameed Akhtar. The mistake has been rectified.

All translations from the Urdu are by the author. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and and translator currently based in Lahore. He also heads the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com