We have just completed another round of elections in Pakistan. Notwithstanding its lack of legitimacy, the rot in Pakistan’s governance systems has creepingly grown out of control over 75 years. We haven’t had a census that reflects an accurate picture of Pakistan’s population for many reasons. The level of deprivation is difficult to accurately collate when the data is flawed.

This article outlines one systematic problem witnessed in Jaffrabad during my relief and rehabilitation social work. Every time I visit Jaffrabad, there is a list of women who have identity card (CNIC challenges). They don’t have one, or it is expired or blocked and getting them updated seems to be impossible? Why?

The Pakistani agency that issues our identity card, NADRA, is considered a jewel of success amongst a failing bureaucracy, and yet it is unable and unwilling to provide adequate service to Pakistanis.

The homes that we are building for the women in Jaffrabad require the beneficiaries to have national identity cards to be able to have land deeds in their names. Many women who qualify have identity card challenges.

I raised this issue with NADRA in Islamabad in 2022 and 2023, and continue to do so in 2024. Lists and locations of families without identity cards were shared to provide them with their constitutional right to be recognised as a citizen.

Two years on, nothing has moved forward on this issue.

Recently, on my last visit to Jaffrabad, I decided to visit the local NADRA office to ‘facilitate the process’ as best I could. As we entered the main Nadra premises, there were hundreds of people sitting and waiting for their turn. I was told the tokens for an appointment/turn were being sold for a fee.

In a place like Jaffrabad, where most residents are non-literate, and they do not know this service is free, where should they go, turn too, for reporting or complain?

I walked into the office of the officer in charge, and asked to meet the gentleman. Mr Ali Sher Jamali was absent, but his colleagues realised I was an unusual visitor and quickly called him. In 5-10 minutes, he arrived at his office. This was approximately 02:30 pm.

I proceeded to share the cases of some of our housing beneficiaries: Mr Zulfiqar and his children, Rakhi and her daughter, and Ms Mumtaz. Others, when they heard ‘Baji’ is at NADRA’s office, tagged along waiting outside hoping finally their cases would be resolved.

Zulfiqar is a widower without a death certificate of his wife, and his age is inaccurately written on his expired CNIC. None of his children have birth registered documents and therefore no B identity cards. He is being asked for verification of his age or to produce a family member to verify him, where there is none available.

Rakhi is widow and doesn’t have a death certificate of her husband. Her expired CNIC is blocked, and also indicates that she is older than her father! Her child has no B-form because her mother doesn’t exist in the system. She needs her age adjusted to accurately reflect she is younger than her father.

NADRA has set rules that there must be at least a one-year gap between siblings in the family tree. Parents must be a minimum of 15 years older than their children. These are all good markers, but who is punching in the information in the NADRA database?

Finally, Mumtaz is a widow, who lives with her parents now. NADRA officials are demanding she produce her brother-in-law for her identity verification. She has no death certificate – nor her own birth certificate. She has parents. She cannot force her brother-in-law to make a journey out of his district, given that he is uncooperative. Therefore, it is an impractical demand. Why can’t her parents verify their daughter instead?

When I discussed each one of these cases with Jamali sb, he immediately agreed to get Mumtaz’s CNIC issued with her parent’s verification. Three days later, I called to check. I understand that Mumtaz went the next day as promised with her parents, and her case was once again refused.

Jamali had informed us that the applicants need to go to the union council officials, who can provide the necessary death, birth or divorce certificates for residents, the required documentation for a CNIC card. Alternatively, a public medical officer at the district headquarter office can provide an official certification of the medical age of the non-literate applicant seeking a card without appropriate documentation.

I raised the practical matter that most residents here are non-literate and are unable to navigate the complex and pelf-ridden public sector halls. Even if they had the money to bribe the local officials for the necessary documents, they are unable to engage, access or comprehend the NADRA requirements. Just watching them observe my conversations with Jamali sb, it was evident they did not understand half of the issues we were discussing and attempting to find a solution for.

Jamali sb said, “Our rules demand official documents, and the age of the citizen cannot be older than their parents, a minimum of 15 years’ gap between child and parent. Almost everyone here has married as a child; they have not registered their births, marriages, divorces or deaths. There is absolutely no comprehension of the need to do so and the domino impact produces the challenges to acquire documentation later.”

We also realised that unregistered child marriages trigger unregistered children born of such unions, and the complex cycle of official invisibility is extended.

Another very peculiar scenario is common in these parts: because of the lack of literacy but also apathy of the official punching in the applicant’s data; the ages on the expired or blocked CNIC are completely irrational. The ages between many siblings are less than a year, which inevitably blocks one sibling out of the NADRA system. Rakhi had this issue as well. Parents being recorded in NADRA’s system as younger than their offspring or barely a couple of years apart from their children was also a widespread issue.

NADRA has set rules that there must be at least a one-year gap between siblings in the family tree. Parents must be a minimum of 15 years older than their children. These are all good markers, but who is punching in the information in the NADRA database and why was it inaccurately uploaded in the first place?

Practically the NADRA officials must provide services for our non-literate citizens, with additional care and handholding for the required documentation. I believe this is their duty and must be institutionalised in their systems.

I tried to explain to Mumtaz, Zulfiqar and Rakhi what the officials were sharing. But I could see the complete blank expressions, especially when I tried to explain that there must be a 15-year gap between parent and child. Practically speaking, they have little idea of their age or distinctions necessary between family members ages.

The rules of NADRA are not sensitive to the requirements of their citizens’ profiles and challenges. Rules and SOPs should accommodate the specific challenges that exist and services required to address them to insure all of the clients manage to get the national identity card. The aim and goal of a service provider must be to get them the national identity card and facilitate them through all the hurdles. But what I see and have witnessed, there is systematic apathy.

Without educated facilitators to help the vast majority of Jaffrabad village folk, there is little chance of them getting their national identity cards. Absentee citizens. Invisible citizens. Unaccounted Pakistanis.

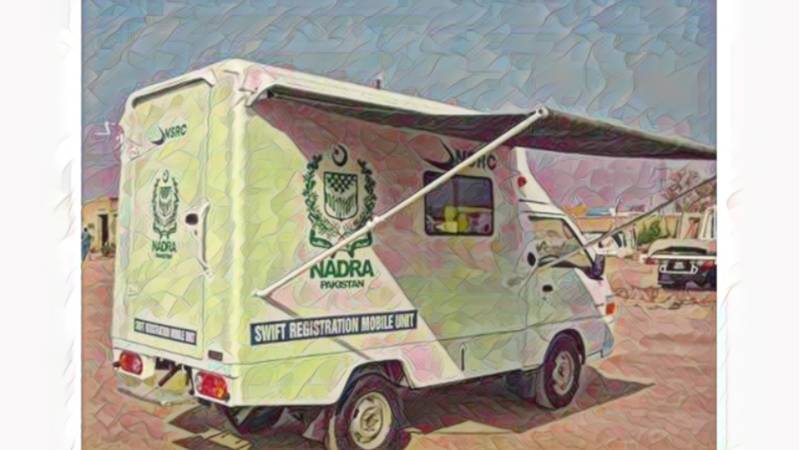

I recall asking Islamabad NADRA officials to send the NADRA mobile units to my villages to provide the identity card services. I was informed that 200 citizens were required to be at a designated point before a mobile unit could be considered. The SOPs for NADRA made in Islamabad do not distinguish between the density of Punjabi villages and Balochistan’s sparsely populated landscape. Who is going to pay for transport and facilitate the sick, disabled or unable? These rules are completely out of sync with the realities on ground, where the clients have very real and specific challenges.

I suggested to Jamali sb that NADRA seriously needs to revisit its human resource strategy and consider a one-window operation with the Union Council officer, a medical officer and a social worker to help each applicant through the process within 24 hours. Moreover, the fees for changing the inaccurate data on CNICs should not be charged; for example, the fee of Rs 1,000 per year changed, up to Rs 5,000, for changing the age documented by NADRA, on their expired/blocked cards.

There are thousands in this district who cannot access a valid national identity card because the systems are set up to fail. Imagine the number of children without identity cards – which means that they are invisible in the census and all other national services for the poor.

NADRA at the federal and district level must revisit their SOPs to develop services that reflect the needs of their clients, not the other way around.

Can we begin by recognising every woman, man and child has the right to be a citizen in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan?

NADRA commits to addressing issues

The author has identified certain policy issues and the problems faced by specific segments of the population in her account. In this context, it must be noted that the state of Pakistan has enshrined the right of citizenship in the Pakistan Citizenship Act. It empowers NADRA with the responsibility to formulate policies and manage operations for efficient and effective issuance of identity documents to legitimate citizens.

The requirement of specific feeder documents, including vital event certificates such as those for birth, death, marriage and divorce, as well as parent's identity cards and their presence or any other government-issued documents, aims to ensure that only legitimate persons obtain identity documents. These stringent measures are essential safeguards against

potential misuse and serve to uphold the integrity of the identification system.

Often, citizens encounter challenges in complying with the requirements of feeder documents. It is important to recognise that the issuance of feeder documents falls outside the jurisdiction of NADRA. Instead, it predominantly rests with the respective local government authorities, i.e. Union councils etc. Nonetheless, NADRA remains committed to partnering with government agencies and makes concerted efforts to train and build capacity of several local bodies.

Furthermore, ensuring the delivery of effective and efficient services remains at the core of NADRA's operations. NADRA has introduced various policy options to facilitate legitimate citizens in cases where documentary evidence is unavailable, such as rectifying unnatural age differences of up to one year without the need for any supporting documents. Extensive ground verification by NADRA Field Teams helps to assuage discrepancies in data convergence. Zonal/ Regional Verification Boards, with the participation of multiple stakeholders, are regularly convened for scrutiny and verification.

NADRA is implementing strategic plans to issue identity documents in areas where there is limited access to static Data Acquisition Units (National Registration Centres). Doorstep facilitation for citizens in remote areas through Mobile Registration Van (MRV) visits is a vital part of our operations. However, scheduling an MRV visit is not subject to any stipulated requirement of a specific number of citizens. Demand for these MRV visits can be raised through NADRA's website, among other available options.

Serving marginalised segments of the society is amongst the stated priorities of NADRA in line with the government's directives. Our specialised teams facilitate registration of these segments by proactively helping women and the differently abled persons as well as making targeted efforts in disaster-affected communities.

The author has raised concerns regarding specific aspects of NADRA's operations, and NADRA acknowledges this feedback with a commitment to addressing the highlighted issues. At NADRA, we value constructive criticism of our policies and operational activities as it helps us adapt our services and facilities to the diverse needs of citizens. We extend our gratitude to the author for her input, reaffirming our commitment to continuous improvement and service excellence. We also invite the author to NADRA headquarters for a detailed briefing to assuage the concerns raised.