In a world defined by divergent viewpoints, NCA’s artist thesis display serves as a poignant exploration of the complex interplay between perspectives, with a myriad of mediums at use. The canvases echo the tangible rage felt within the human spirit, challenging prevailing norms and questioning the very essence of identity, inviting viewers to contemplate the intricacies of personal and collective struggles.

Noor’s art reminded me of Albert Aurier’s momentous essay ‘Le Symbolisme en Peinture”-- therein, Aurier talks of symbolism in art:

“The goal of painting . . . cannot be the direct representation of objects. Its end purpose is to express ideas as it translates them into a special language…all the while remembering that the sign, however indispensable, is nothing in itself and the idea alone is everything.”

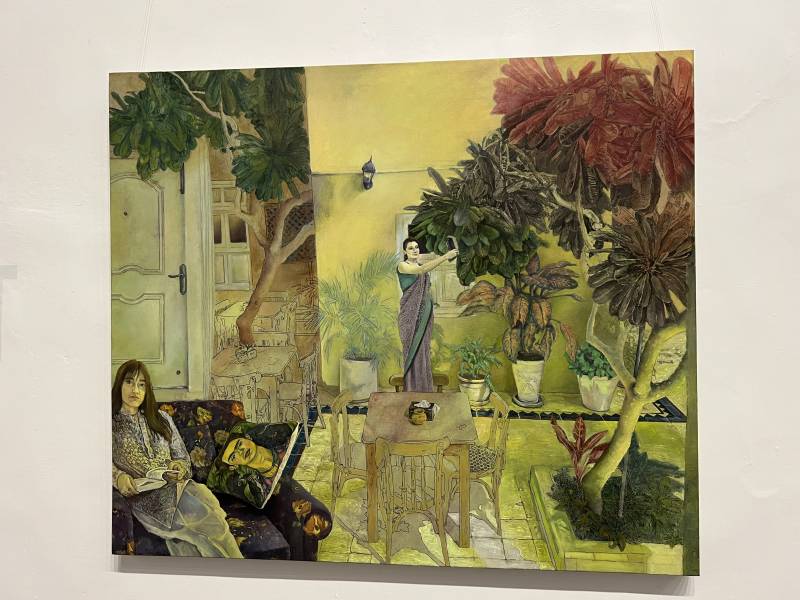

This sentiment is ripe in Noor-ul-Huda’s work and she captures it in such a dreamlike trance that you feel suspended between lullabies sung by the morphing color palette of her paintings. Her work explores the dissociation of existence in terms of human relationships and the liminal space around them. “To exist in a space yet to not be there,” she said, walking with me back and forth between her displays and pointing out the minute details.

Noor’s painting, specifically the ones titled ‘Farida ke Baagh Mein Vincent ki Shaam’ and ‘Maghreb’ were striking– bound by the fading quality of a memory and the slow corrosion of time. When talking about the medium, she pointed to specific portions that molded together and yet disconnected– two women, suspended in time, looking out at the audience in a manner that said, “Do you see me? I am looking at you– are you looking at me? Am I the persistent voyeur, or are you?” I look closely and there is a third set of eyes– Frida Kahlo’s visage imprinted on a cushion in the settee. “The treatment I evolved… is in layers… I left it in washes because I was disconnecting the space, yes, but also the past and the present.”

Degas’ work has always been to me a study in fluidity– from The Rehearsal to The Tub. Noor’s work too is a reminder of the study of motion in art– especially owing to the fact that she combines the viscosity of paint with the motion of life shows up in an incredible, harrowing manner.

Iman’s art was striking– I had a grin on my face as soon as I saw it. If other pieces had subtlety to the manner in which they countered the experience of being a woman in a patriarchal society, Iman’s work took the narrative and turned it to face the glaring problem. I thought of the sillage in the walls in monsoon. Water seeps through, the plaster cracks, the wall crumbles, and then we see the glaring issue. Iman’s work is evocative, gritty and quite literally, layered in the way it perceives the problem of existing in a society that is so people focused. I was overjoyed by the warmth and passion with which she dealt with something that leaves one grappling with their own identity.

Sometimes, art feels like a bath of cold water on a December morning. That is exactly what Iman encapsulates– through a medium that stands out.

“You have been to the tailor, right? You will talk them through your measurements, and it still ends with them saying– no, this might be too ill-fitting. Add to that the fact that when I joined a musical society in NCA, the one question I got most often was– you wear the hijab. Will you seriously sing and play music?”

She said it all with such a bright smile on her face and I could see that she had taken the shame and humiliation that society casts on any person wanting to exist outside the box, and channelled it into her art. It pinches, yes, as the intricately used safety pins in her work represent, yet on the outside all one sees is an expertly put together net of sorts– a protective element– yet only the wearer of the shroud comprehends the angst and pain of donning it.

In Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto, Marinetti’s translation of the work best describes what Iman captures and how she transcends the traditional realms of expression:

“Let’s… proclaim the absolute and complete abolition of finite lines and the contained statue.”

Sometimes, art feels like a bath of cold water on a December morning. That is exactly what Iman encapsulates– through a medium that stands out.

Maidah Waqar Butt’s art reminded me of my childhood affinity for the Indus Valley Civilization– there was lately conversation on a lot of platforms, where people argued what historical period was their childhood obsession. The consensus was mostly the Roman Empire or the Egyptian civilization. I was instantly reminded of my love for the Mesopotamian and Harappan architecture, begging my parents to take me to visit the sites (unfortunately, we never did). Maidah’s expertly created figurines that give these neolithic sculptures color and life took me back about ten years ago to that time. Venus of Willendorf was one of those figures I always looked at with awe– when we currently see the ‘celebration’ of the female form, what we see is it reduced to its aesthetic appeal; it exists to be beautiful and to be consumed.

Maidah’s art steps out of the 21st century bonds of everything existing for the consumer and takes us back to an era that was rooted in naturalism– it celebrated the female form and its anatomy, bringer of life, not stuck in the plastic confined of a neoliberal world that reduces it to nill. Neolithic figurines from Europe, to Asia to Africa looked at the anatomy of the female body with reverence, I’d even argue, worshipped it– it was she that ensured survival.

Venus of Willendorf was one of those figures I always looked at with awe– when we currently see the ‘celebration’ of the female form, what we see is it reduced to its aesthetic appeal; it exists to be beautiful and to be consumed.

Maidah, in her pieces such as ‘embroil’ and ‘bearing/baring,’ takes the reins and steers the conversation back towards our roots. I asked her, “Have you been criticized for your representation of the raw, vulnerable female form without the confines constituted by patriarchy?” as she showed me some of her expertly created clay figurines. “Of course, from a lot of people. Especially ones closest to me– but this is what I enjoy about the representation of the female form in Neolithic art. It doesn’t shy away, and neither did I.”

Vania Mazhar’s representation of the mundanity of life struck me as soon as I walked into the gallery– her display is titled “Synchronicity II”-- “...many miles away, there’s a shadow on the door.” Looking at Vania’s art, I was struck by the synchronization of the perspectives, embedded with the glimpse of a daughter looking at the roaring cadence of what her pupils grab, and the image of it imprints into her retina– just for it to become a memory. Like a perfumed envelope, it haunts and it warms the heart, an overpowering sense of fleeting nostalgia grabbing you and telling you– you have lived this, and so have I.

You watched it happen and now you shall remember, remember, remember all those fleeting memories of your personhood. It is a whiplash and a soothing balm at the same time; to my eye, it combines at the core of it the delicate memorialization of Realism with the rebellious strokes and stylistic endeavours of Impressionism– saying “this is remembrance– I am remembering it in the haze of my memory and embracing the etches of it, capturing the coherence of this existence rather than the semantics of it.” “Watching the Same Drama Everyday” and “Sebastian Watching A Video” especially struck me in the manner they manage to capture what Vania termed “the mundanity of existence.”

“I am sort of searching for these mundane moments around my house… looking at my father just being himself, that’s where the inspiration strikes. I am trying to find the balance between a sketch and a painting,” she explained to me.

Looking at Vania’s artwork reminded me of Mary Cassatt– her interplay of perspective and dimensionality, combined with sheer, raw, sentimentality was reminiscent of Cassatt’s The Child’s Bath.

Meeral Mirza’s work in textile is as if walking into the pages of the famed Firdawsi’s Shahnameh, or finding yourself in Isfahan, looking at the delicate cuerda seca tile work of the Mihrab from Madrassa Imami. It is the perfect union of teachings and visuals of Islamic Arab scholars like Abu Ma'shar– an amalgamation of culture, faith and the Golden Age (the intricate gold details wink and wave in the subtle light, layering on top of each other to create elements perhaps only the sun can shine a light to– watercolor on top of Wasli, and digitally printed onto Mesuri fabric). It is a brilliant marriage between the intricacies of decorative detailing and perspectives on textile.

“I'm Kashmiri. In Kashmir, like, astrology is a pretty big thing… there is Vedic astrology, and then the Persian and Islamic one. The visuals of the latter spoke to me… astrology is basically the father of science. Because first we had astrology, then we had alchemy, and then from that we have chemistry as we know it today. And the second thing is that stocks are also like a prediction sort of thing, right? So if we're gonna make fun of women for believing in astrology, then we can make fun of men for believing in, like, you know, the stock market.”

The medium adds an inherent sense of delicacy and airiness that permeates the pieces and draws the viewer in. But it is much more complex– Meeral’s artist statement explains: “Astrology is a controversial subject… Science and mathematical calculations surrounding this field are what distinguish it from any superstitious pseudoscience. I have created my own visual vocabulary to find the junction between Persian style astrological paintings and textile design.” Each piece is a brilliant homage to a specific astrological sign, an interplay of texture and light and fine detailing.

In a talk with Meeral about the implications of her choice when so many women are demonized for believing in astrology, she put it best to the face of patriarchal critics: “I'm Kashmiri. In Kashmir, like, astrology is a pretty big thing… there is Vedic astrology, and then the Persian and Islamic one. The visuals of the latter spoke to me… astrology is basically the father of science. Because first we had astrology, then we had alchemy, and then from that we have chemistry as we know it today. And the second thing is that stocks are also like a prediction sort of thing, right? So if we're gonna make fun of women for believing in astrology, then we can make fun of men for believing in, like, you know, the stock market.”

Syeda Ailia Hassan’s work is a study in nostalgia, combined with a fusion of the contemporary to create furniture and products that transcend the fine lines of a relatively stiff medium to leave you awed at the sheer delicacy and wonder of her craft– she combined brass plating, beautifully melded into wood. Combining the sharp and hard contours of wood, stylized to be contemporary and experimental with the traditional elements of brass make it stand out– it is in a way reminiscent to me of Futurist elements of design combining with the traditional elements of post-Islamic metalwork, intricately combined. The past, holding onto the future and the present– a study in time.

Ailia stated that her main inspiration behind her work has always been mother– “This craft you can see on the brass, my mother used to sculpt it. She did it for 25 years.” The fine contours in the wood are topographical representations of the place where the said art was first founded. Qalam-Zani in Persian, she explained, is an amalgamation of the words “pen” and “hitting”-- the perfect word for it.

She further explained: “I really wanted something which was small and which contained all the elements. I had water and the birds and the, and the glass. Each part of the console and the mirror are in this.” Minimalism, she explained, is lovely, but so overdone that she wanted it to be minimal in a manner that combines the love for texture that we have as Pakistanis. She laughed, explaining how her identity as an artist translates into her work too: “So when I think about myself as a person, I'm a very extra person, very extra personality with a very minimal…what do you call it? Sugar coating? And I think my pieces show that.”

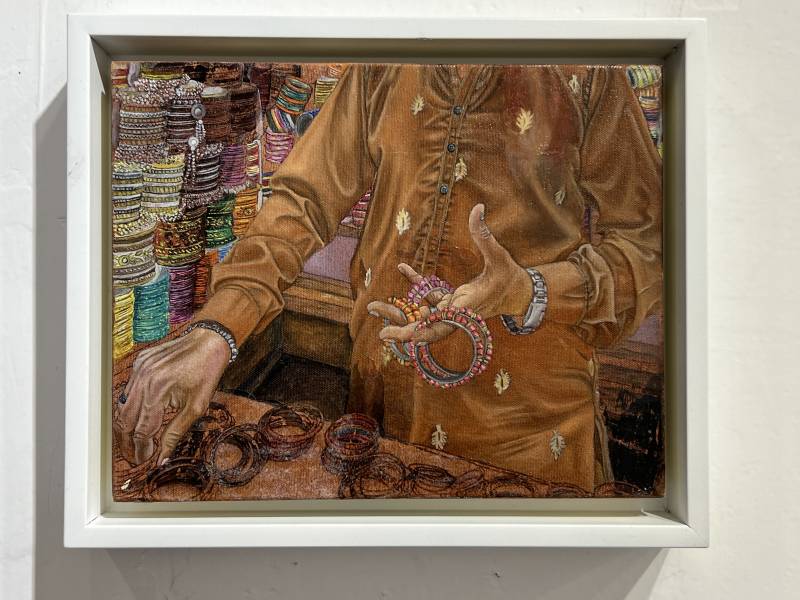

Sumaiya Hayee’s work is a study not only in the colours and intensity of the life in Old Lahore and its streets, strewn with life that is aeons apart from the sanitary life on the roads and streets of the more ‘modern’ Lahore– the Lahore that boasts its elitism and forgets the existence of Old Lahore and its people. Sumaiya explained to me that she herself is from Androon Lahore, and she wanted to pay homage to the beauty in the little moments of life there– especially to the working class there.

Rage rips you apart and then puts you back together. I am reminded of Munch and The Scream, originally aptly titled Despair– to take emotions rooted in the real and the binary and project them into a world with intense hues, colors and morphing perspectives to amplify them and give them a sense of reality that is so heightened that all your sense are attached to viewing it.

“We only go to them when we need work done– the tailors, the shopkeepers– we refuse to see them as human beings that have a life apart from perhaps… serving us,” she put aptly. Her art is rich and experiments with texture and color while also staying true to Realism– it is as if the images of life are superimposed to give one a view into what we so often ignore; the color and beauty of it that we forget in our own obsession with self and individuality in a capital driven society.

Fatima Ahmed’s work is a study in rage and personhood– a metamorphosis reminiscent of Kafka’s titular character Gregor Samsa. Rage rips you apart and then puts you back together. I am reminded of Munch and The Scream, originally aptly titled Despair– to take emotions rooted in the real and the binary and project them into a world with intense hues, colors and morphing perspectives to amplify them and give them a sense of reality that is so heightened that all your sense are attached to viewing it. Fatima too, manages to do it in a manner that reminds me of the German Expressionists of the early 20th century– not to show what the eye sees but to show what the mind and heart feel. Munch, when asked about his painting, said: “And I sensed a great, infinite scream pass through nature.”

When I talked to Fatima, she better explained her artistic vision: “I was in the midst of some realizations… boundaries between the inner and outer self. There was a warped sense of responsibility and keeping these separated, so the rage came out in some of the paintings. I really like stream of consciousness in literature, and wanted that in my art. This is an exploration of identity.”

Ayla Zahir Kayani’s work crosses the realms of ordinary to leave you suspended in ways that make you question your own reality and existence– ‘Forced Convergence’, ‘Serendipity in Existence’ and ‘Somatic Reflux’ are all pieces that stand out and hold the viewer captive– it reminds me of a scent that permeates the air so strongly that it overpowers. First you retch, unable to understand whether it is disgust, and then you grow accustomed to it and a sense of calm takes over. Yet the magic still permeates.

A lot of Ayla’s work is about reflection and uses a reflective medium that also combines fragility and sensitivity. One of my personal favorites is perhaps the most jarring– a sink clogged with gunk and water, pooling at the center. You are unable to find your own reflection. You look up, searching for a mirror and all that stands is a ghost of the said mirror, shadow imprinted on the wall in red but never seen. You don’t have a way out to look at your reflection in a manner that is not distorted; but it needs time to be spent with it to understand the intricacy of it. Another one is a cage enclosing a set of white feathers at the center of the room. Purity, plucked and placed in confines. Ayla explained her use of engine oil: “And although you can't see your exact reflection, you know that there exists a reflection. And I was using engine oil exactly for that. When untouched… you can see yourself in it.”

Muneeba Zahid Khan’s artist statement best pays homage to her identity, translating it into her work. “She specializes in miniature painting and explores themes of identity and displacement through her artwork. Growing up with her first adoptive family, she often felt like a shadow caught between two worlds… she expresses these difficulties through her art, using medical reports and x-rays as her canvas.” The presence of hollow, shadowy figures permeates her work in a way that is jarring– at first glance, you are looking at expertly put together medical records, joined together, as if an exploration of pain itself. At a nearer glance, you see the culmination of whose pain it is.

As someone that has been chronically ill, I know it best– doctors’ offices, being suspended between reality and truth, feeling as if you are a file number or a doctor’s note. Never feeling like a whole person, merely a shadow of a shadow. When you look closer at Muneeba’s work, you see the person shine through. In x-rays and MRIs, she makes artwork such as ‘Posheeda’, ‘Are You There?’ and ‘Suffering’-- a child pulled apart and grieving, a woman yin-and-yang, lying in foetal position. The medical sanitary is given a humanistic perspective. In conversation with Muneeba, she explained it best– “You always remember, no matter where you are displaced, thus the MRI. Science and art are very divorced fields but I was previously in medicine, but then I decided to go into arts. I think perhaps that was a factor too.” Her medium stands out– because she is perhaps the first person to find the middle route between the two.

In the culmination of this artistic journey, the thesis display stands as a testament to the enduring power of art in unravelling the threads of existence. As viewers engage with these visual narratives, they are invited to transcend the confines of conventional thinking and embrace a collective dialogue that dismantles the chains of not contemplating the threads of our lives. Only through art, we can call to redefine personhood in a world yearning for unity amidst discord.