Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif has nominated General Asim Munir to be the next army chief, putting an end to months of speculation.

In no other country does anyone pay much attention to the choice of army chief. But Pakistan is no ordinary country.

Noting that four army chiefs have governed the country under martial law, UCLA Professor Stanley Wolpert once observed that the army’s conduct was akin to that of a “wolf hound” which occasionally turns on its master.

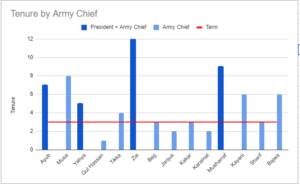

The term of the army chief is three years. In most countries, including India, the army chiefs rarely get an extension. Among the four coup makers, Ayub’s term was extended by four years, Yahya’s by two, Zia’s by nine and Musharraf’s by six.

Even when they are not ruling the country, army chiefs often get their terms extended. General Musa served for an additional eight years, General Tikka for one additional year, and Generals Kayani and Bajwa for an additional three years each.

Prime Minister Imran Khan, who many feel was appointed at the pleasure of the army, extended General Bajwa’s term in a terse letter, citing some vague concerns about national security. Perhaps that was the price Imran had to pay for ensuring that the army would not remove him from office. From that point onwards, Imran was often heard saying that he and the army were on the “same page.”

Bajwa, who had waxed eloquent about “hybrid warfare,” will be remembered even more for instituting “hybrid democracy.” This extra-constitutional experiment belied his recent assertion that he did not want the army to interfere in politics.

Sometime last year, the army realized that Imran was performing poorly and wanted him removed from office. He was ousted as prime minister when he lost the support of the majority in the National Assembly.

To the army’s surprise, Imran launched a national movement demanding that new elections be held. He derided the government that replaced him as imported, and blamed the US and the “neutrals,” a code word for the army, for deposing him from office.

He held huge rallies throughout the country. His party began winning by-election after by-election. And he began to appear in the international media.

It did not stop there. Imran penetrated the inner sanctums of the army. Bajwa’s “hybrid democracy” experiment had boomeranged on him.

What are we to expect from General Asim Munir? In a democracy, the army chief is not supposed to govern the country, either directly or indirectly. He can only do so after he has retired. That’s what happened in the UK with the Duke of Wellington, in the US with George Washington and Dwight Eisenhower, and in France with Charles de Gaulle.

The army chief is not supposed to meddle in politics nor is he supposed to influence either the economic or foreign policy of the country. In particular, he is supposed to live within the defence budget given to him by the government. The army is not allowed to either create or run civilian institutions or grant extensive land holdings to its serving and retired officers.

Will General Asim Munir break from the past and usher in a new era in civil-military relations? Will Pakistan finally turn into a democratic republic? Before we get swept away with the fever of idealism, let’s review what history tells us.

When General Ayub, the first coup maker, elevated himself to president, promoted himself to Field Marshal, and appointed Gen. Musa as army chief, he did so because he was convinced that Musa would not threaten his governance. That turned out to be true.

Of course, Ayub was an army man and during his decade-long tenure, the army entrenched itself deeply into the political, economic and foreign affairs of the country. When he appointed General Yahya as army chief, he thought he would be a loyalist like Musa. But Ayub’s luck ran out. In March 1969, Yahya deposed him.

The disastrous end of the 1971 war resulted in Yahya’s removal from office. When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto appointed General Zia as army chief, he was convinced that Zia would be a compliant man. He was proven wrong. The same thing happened when Nawaz Sharif appointed General Musharraf.

In Pakistan, more than once, army dictators and prime ministers have regretted the army chiefs they appointed.

The army as an institution is so deeply embedded in the body politic of the country that Brooking’s Stephen Cohen called it Pakistan’s largest political party.

Why? Its vital interests are at stake. Even though they did not mount a coup, Generals Kayani and Bajwa were given extensions, in part to prevent a coup from happening by letting the army continue to engage in rent seeking behaviour.

The top brass of the army has captured the strategic heights of the economy. For decades, the army has profited enormously from its commercial ventures which span a range of industries and businesses. This has been well documented by Ayesha Siddiqa in Military, Inc. Perhaps the most ostentatious display of its wealth is the posh “defence housing societies” that are found in major cities around the country. Elite capture cannot be wished away.

Defence spending accounts for a significant share of the national budget, ostensibly to strengthen national security. The army continues to maintain an aggressive stance toward India, fuelling an expensive and dangerous arms race that’s inclusive of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles. The defence budget cannot be critiqued by the National Assembly.

The first ever national security policy issued by Imran Khan claimed to be citizen-centric but it made the egregious assertion that the “guns versus butter” tradeoff was archaic. Thus, Pakistan could afford to spend more on defence without compromising on economic growth. Such a miracle has not been achieved anywhere else in the globe. It defines the laws of economics: “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” Everything has an opportunity cost. There is little doubt that the army played a role in writing the document.

The idealist in me would like the new army chief to conform to the higher standards of democracy. But the realist doubts it. Culture cannot be changed overnight, especially when it would mean the loss not only of the status of Pakistan’s “biggest political party,” which is what Professor Stephen Cohen called Pakistan’s army, but also the loss of billions in wealth not only for the current generation of general officers but for generations to come. They will not allow themselves to be disenfranchised without putting up a big fight.

In no other country does anyone pay much attention to the choice of army chief. But Pakistan is no ordinary country.

Noting that four army chiefs have governed the country under martial law, UCLA Professor Stanley Wolpert once observed that the army’s conduct was akin to that of a “wolf hound” which occasionally turns on its master.

The term of the army chief is three years. In most countries, including India, the army chiefs rarely get an extension. Among the four coup makers, Ayub’s term was extended by four years, Yahya’s by two, Zia’s by nine and Musharraf’s by six.

Even when they are not ruling the country, army chiefs often get their terms extended. General Musa served for an additional eight years, General Tikka for one additional year, and Generals Kayani and Bajwa for an additional three years each.

Prime Minister Imran Khan, who many feel was appointed at the pleasure of the army, extended General Bajwa’s term in a terse letter, citing some vague concerns about national security. Perhaps that was the price Imran had to pay for ensuring that the army would not remove him from office. From that point onwards, Imran was often heard saying that he and the army were on the “same page.”

Bajwa, who had waxed eloquent about “hybrid warfare,” will be remembered even more for instituting “hybrid democracy.” This extra-constitutional experiment belied his recent assertion that he did not want the army to interfere in politics.

Sometime last year, the army realized that Imran was performing poorly and wanted him removed from office. He was ousted as prime minister when he lost the support of the majority in the National Assembly.

To the army’s surprise, Imran launched a national movement demanding that new elections be held. He derided the government that replaced him as imported, and blamed the US and the “neutrals,” a code word for the army, for deposing him from office.

He held huge rallies throughout the country. His party began winning by-election after by-election. And he began to appear in the international media.

It did not stop there. Imran penetrated the inner sanctums of the army. Bajwa’s “hybrid democracy” experiment had boomeranged on him.

What are we to expect from General Asim Munir? In a democracy, the army chief is not supposed to govern the country, either directly or indirectly. He can only do so after he has retired. That’s what happened in the UK with the Duke of Wellington, in the US with George Washington and Dwight Eisenhower, and in France with Charles de Gaulle.

The army chief is not supposed to meddle in politics nor is he supposed to influence either the economic or foreign policy of the country. In particular, he is supposed to live within the defence budget given to him by the government. The army is not allowed to either create or run civilian institutions or grant extensive land holdings to its serving and retired officers.

Will General Asim Munir break from the past and usher in a new era in civil-military relations? Will Pakistan finally turn into a democratic republic? Before we get swept away with the fever of idealism, let’s review what history tells us.

When General Ayub, the first coup maker, elevated himself to president, promoted himself to Field Marshal, and appointed Gen. Musa as army chief, he did so because he was convinced that Musa would not threaten his governance. That turned out to be true.

Of course, Ayub was an army man and during his decade-long tenure, the army entrenched itself deeply into the political, economic and foreign affairs of the country. When he appointed General Yahya as army chief, he thought he would be a loyalist like Musa. But Ayub’s luck ran out. In March 1969, Yahya deposed him.

The disastrous end of the 1971 war resulted in Yahya’s removal from office. When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto appointed General Zia as army chief, he was convinced that Zia would be a compliant man. He was proven wrong. The same thing happened when Nawaz Sharif appointed General Musharraf.

In Pakistan, more than once, army dictators and prime ministers have regretted the army chiefs they appointed.

The army as an institution is so deeply embedded in the body politic of the country that Brooking’s Stephen Cohen called it Pakistan’s largest political party.

Why? Its vital interests are at stake. Even though they did not mount a coup, Generals Kayani and Bajwa were given extensions, in part to prevent a coup from happening by letting the army continue to engage in rent seeking behaviour.

The top brass of the army has captured the strategic heights of the economy. For decades, the army has profited enormously from its commercial ventures which span a range of industries and businesses. This has been well documented by Ayesha Siddiqa in Military, Inc. Perhaps the most ostentatious display of its wealth is the posh “defence housing societies” that are found in major cities around the country. Elite capture cannot be wished away.

Defence spending accounts for a significant share of the national budget, ostensibly to strengthen national security. The army continues to maintain an aggressive stance toward India, fuelling an expensive and dangerous arms race that’s inclusive of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles. The defence budget cannot be critiqued by the National Assembly.

The first ever national security policy issued by Imran Khan claimed to be citizen-centric but it made the egregious assertion that the “guns versus butter” tradeoff was archaic. Thus, Pakistan could afford to spend more on defence without compromising on economic growth. Such a miracle has not been achieved anywhere else in the globe. It defines the laws of economics: “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” Everything has an opportunity cost. There is little doubt that the army played a role in writing the document.

The idealist in me would like the new army chief to conform to the higher standards of democracy. But the realist doubts it. Culture cannot be changed overnight, especially when it would mean the loss not only of the status of Pakistan’s “biggest political party,” which is what Professor Stephen Cohen called Pakistan’s army, but also the loss of billions in wealth not only for the current generation of general officers but for generations to come. They will not allow themselves to be disenfranchised without putting up a big fight.