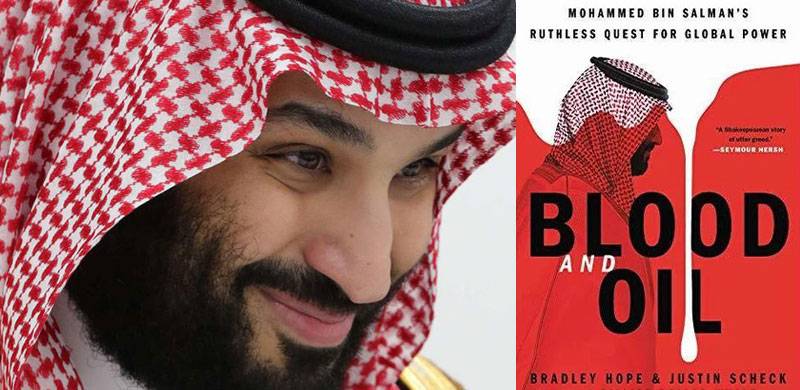

Maverick, unpredictable, volatile, albeit a visionary and cold-bloodedly authoritarian who struck gold at an early age in the anachronistically medieval and tribal structure of the Saudi royal family… these are a few adjectives that come to mind for Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS) after reading Blood and Oil Mohammed bin Salman's Ruthless Quest for Global Power, written by Bradley Hope and Justin Scheck.

For MBS and Saudi watchers, the events narrated in the book might be familiar since most date back to only a few years. It is the crucial context and an essential peep into his mind and the workings of the royal court that make the book a fascinating read.

Starting his journey as an aloof and almost taciturn teenager among the princes, Mohammed privately despised the profligate and spendthrift lifestyle of the Al-Saud family. He even refused to study abroad, foregoing a customary training session of young royals on how to fritter away the kingdom’s oil wealth. Having a virtually ‘hand-to-mouth’ governor of Riyadh for almost five decades for a father, especially when compared to obscenely wealthy princes, was the main source of inspiration for him to make Saudi Arabia an attractive destination for foreign investment in a post-oil era. Take the example of rounding up and detaining wealthy and powerful princes at the Riyadh Ritz Carlton, including the flamboyant Waleed Bin Talal, coercing them into handing over billions of dollars accumulated through corruption over the years.

His pipedream presented in the book is to turn the historical tables and make Saudi Arabia a safe and attractive destination for American and Western investors, while allowing no room for dissent domestically, especially among princes and their families.

As the book moves along at a spellbinding pace normally associated with a Godfather-like thriller, a sinking feeling of foreboding grips the reader -- for more chilling details that come with an alarming regularity. The writers spare the reader of the unnecessary rhetorical pugilism, which may not have been required in the presence of cold individualism demonstrated in abundance by the prince – such as real-life incidents of abductions, disappearances and deaths. His pipedream presented in the book is to turn the historical tables and make Saudi Arabia a safe and attractive destination for American and Western investors, while allowing no room for dissent domestically, especially among princes and their families.

The killing of one-time supporter of the Al-Saud, The Washington Post columnist, Jamal Khashoggi, remains the biggest blot on the crown prince’s reputation. The straw that broke the camel’s back, as per the book, was when Khashoggi made a seemingly provocative decision to talk to an investigator working for the families who had sued Saudi Arabia for the 9/11 attacks. MBS could see his “visionary” project of NEOM—a 26,000 square kilometres of land to be developed for business, a futuristic science fiction Dubai-on-the-Red Sea multiplied by a hundred—go up in smoke before it was even born. And his unrealistic dream to get Saudi ARAMCO listed on the New York Stock Exchange had started to seem like an improbable near future occurrence.

His reign is replete with mind-numbing faux pas. His ‘Vision 2030’ seems to have been obscured by the methods used to get his way, both inside and outside the kingdom. However, critics argue that apart from the Khashoggi murder, which earned him the unenviable epithet of the “bone saw man”, his reckless haste to bring Saudi Arabia at par with normal societies, where women drive cars and people go to cinemas, musical concerts and theaters, for instance, has some merit.

The memories of former Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri’s resignation on TV still rankle. His crime was to form a coalition government with the help of Hizbollah, an Iranian proxy in the eyes of MBS. Then there is the case of house arrest of former Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Nayef in 2019, when he was summoned at an early hour and unceremoniously relieved from his duties and title. It seems the disappearances of a few princes and Prince Miteb Bin Abdullah, son of King Abdullah, and his siblings being deprived of billions of dollars has not dented MBS’s grip on power.

In the absence of a fair and impartial legal system guaranteeing due process of law, democracy and fundamental, will foreign companies be able to justify investments worth billions of dollars in Saudi Arabia?

The prince’s lack of exposure to societies bound by rule of law is well known among the world business elite. For instance, when his sister Hassa was visited by the French police in Paris to probe allegations of loutish behaviour, MBS had reportedly told her lawyer that “my father spoke to the President Francois Holland, so everything should be fine.”

The big questions that remain unanswered are whether in the absence of a fair and impartial legal system guaranteeing due process of law, democracy and fundamental, will foreign companies be able to justify investments worth billions of dollars in Saudi Arabia? And will al-Ula become a new wonder of the world, where some 2000 years ago, Nabateans carved facades into sandstone cliffs similar to Petra in Jordan? Whether the Prince’s purchase of Salvator Mundi bought from a Christie’s auction for a whopping $450 million along with rest of his art collection will adorn the yet to be constructed art gallery in his quixotic fantasy city? And, most importantly, will the Saudi society liberalise enough to allow public viewing of the Da Vinci painting depicting Jesus Christ making the sign of the cross while holding the transparent orb in his left hand symbolising his role as the “Saviour of the World?”

Only time will tell.