A young boy–or girl—dreaming of travels to far lands and an old man in his rocking chair fantasising of adventures in distant climes have one thing in common: They reflect the innate desire in all of us to travel in search of knowledge and adventure.

Almost everyone has heard of the great travellers and explorers such as Marco Polo, Columbus, and to a lesser extent Lewis and Clark in America sent by President Jefferson to explore the American west. People everywhere know about modern travellers who went to the moon—Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon in 1969 and John Glenn. Then there are travellers in popular fiction. The Time Traveler in The Time Machine by HG Wells, Phileas Fogg in Around the World in Eighty Days, and Captain Nemo in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, both by Jules Verne, are well-known fictional characters through movies and documentaries; as indeed is Captain Kirk of the starship Enterprise in the Star Trek TV and movie series, and Indiana Jones in his many adventures.

Our intrepid traveller, Ibn Battuta, belongs in this company of iconic characters. Though there is a crater on the moon named in Battuta's honour, few have heard of Battuta in the West. There are however some standard books on Ibn Battuta, for example: The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveller of the Fourteenth Century, with a new preface by Ross E. Dunn (2012), though I wonder if Dunn made a conscious choice in the title to echo The Adventures of Robin Hood? There is The Travels of Ibn Battuta to India, the Spice Islands, and China by Noel King and Albion M. Butters (2018), and Ibn Battuta in Black Africa, edited by Said Hamdun and Noel King (2009).

Also see the excellent recently made documentary, In the Footsteps of Ibn Battuta, by the educational enrichment company ‘In the Footsteps of History,’ which uses 3D games and digital activities to bring history to life for students. Co-founded by modern-day explorer and educator Denis Belliveau, who once spent two years retracing Marco Polo’s footsteps and long-time educational technology specialist, Lisa Taylor, you can learn of their other ‘journeys’ here.

Battuta’s travels

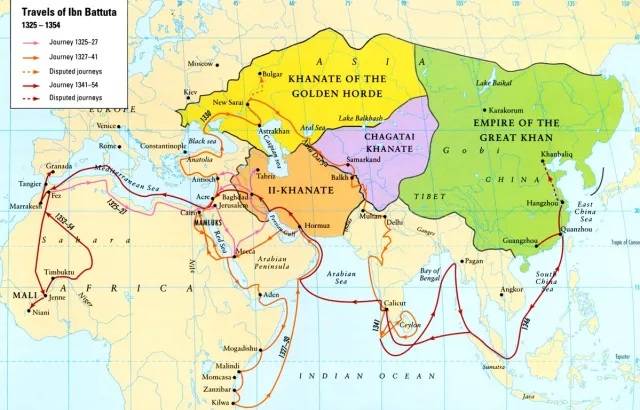

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (1304–1368/1369), widely referred to as Ibn Battuta, was a traveller, explorer and scholar from Tangiers in what is presently the nation of Morocco. His journeys would take him to the furthest ends of what was then the Muslim world—to China at one end, Russia at the other and into Mali and Saharan Africa. He had initially calculated that the Hajj to Mecca and back would not take him more than one to two years. In fact, once he left Tangiers, he traveled for the next three decades. From 1325 to 1354, he visited most of North Africa, the Middle East, East Africa, Central Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, China, the Iberian Peninsula, and West Africa. Towards the end of his life and as a response to the request of the ruler of Tangiers, he dictated his journeys which spread over a thousand pages. His title A Gift to those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling, was sensibly reduced to Rihla or Travels.

Ibn Battuta, who had set out to perform the Hajj, ended up by performing it five times in the course of his travels. By the end of his journeys Ibn Battuta had travelled some 75,000 miles, five times longer than MarcoPolo.

I asked myself what drives someone to travel and explore different lands for so many years of his life? Was it a desire to accumulate wealth and become rich? Or to become powerful and influential? Perhaps to find fame? I believe a factor that drove our explorer was his simple belief in pursuing knowledge. Ibn Battuta had wanted to seek out and meet other scholars on his journey. His attitude to knowledge is understandable in a scholar of religion. We will return to the theme in the next section.

It is noteworthy that the impetus for Battuta’s journey was the Hajj. The Hajj is one of the five pillars of the Muslim faith along with the declaration of faith, prayers, fasting and charity. The challenge of the Hajj is that it meant traveling across difficult deserts and mountains and facing danger on the road. Remember that was the time when there were virtually no communications, no telephones, no buses or cars, no airplanes because young Battuta lived in the 14th century. But Battuta had a passion to perform the Hajj come what may.

Only 21 years old and fresh from his religious studies, Ibn Battuta, after saying goodbye to his mother and father set off alone with his trusty donkey with very few clothes or belongings. When he returned decades later his father had passed away several years earlier and just before he arrived in Tangiers, he learnt that his mother had died. There was nothing to hold him back now, so he set off once again on his travels. This time he decided to explore his own continent and headed for Mali. His pattern of travel was not organised or structured, it was rather like go with the flow, he may have been traveling north and then he would if circumstances dictated, swing to the south, east or west.

It was the 14th century and travel such as performing the Hajj was fraught with dangers as the roads, such as they were, were beset with brigands and gangs of thieves. There was always the danger of falling ill. Besides, arranging a place in a friendly caravan took time and negotiations. Yet Ibn Battuta found that not only did bandits and thieves show him consideration as a scholar, but rulers tried to keep the main roads protected and provided lodgings, food and even money. These rulers considered it their duty to protect and support devout Muslims performing the Hajj.

Battuta was received with much kindness by people on his journey: the king of Delhi appointed him a judge, the Mongol khans, now champions of Islam and dominating large parts of what was once the eastern Muslim empires, and even their wives, invited him to accompany them. Even bandits, as we saw above, showed the scholar consideration.

Battuta does not seem to have been a complicated man. He was a simple man. An intelligent and scholarly man and judging from the way people responded to him with hospitality and welcome, he clearly possessed a certain amount of charm. Otherwise, he would not have had the hospitality and warm reception shown to him on his journeys. On the first leg of his travels across north Africa on his way to perform the Hajj, we already see certain patterns of his travels. His determination: when he falls ill he asks to be tied to his animal so he can continue the journey. His predilection for marriage is also clear, although his first marriage with the daughter of one of the caravan leaders ends in divorce. Not deterred, he arranges another marriage to another woman.

Ibn Battuta met two famous mystic Sheikhs in Alexandria. Both predicted that he would one day make a name for himself and would become famous. One was Sheikh Burhanuddin, who foretold the destiny of Ibn Battuta as a world traveller. He advised him thus: “You must visit my brother Fariduddin in India, Rukonuddin in Sind, and Burhanuddin in China. Convey my greetings to them.” Another pious man Sheikh Murshidi interpreted the meaning of a dream of Ibn Battuta in which he was flying about to mean he would become a renowned world traveller. On the first leg of his travels across north Africa on his way to perform the Hajj, we already see certain patterns of his travels. His determination: when he falls ill he asks to be tied to his animal so he can continue the journey. His predilection for marriage is also clear, although his first marriage with the daughter of one of the caravan leaders ends in divorce. Not deterred, he arranges another marriage to another woman.

While his aim was to perform the Hajj he hoped to also meet and learn from the famed scholars in the great cities of the Muslim world such as Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad, and Mecca. This he did successfully, meeting some of the most respected contemporary scholars along the way. The learned men seem to have taken to him as a bright young Arab scholar and encouraged him, often giving him references to other scholars. An aspect of his writing which is quite appealing and somewhat innovative for us was the detail he provides about the foods and cuisine and delicious dishes he was served. So, we have a unique insight into how people lived and what they ate across the Muslim world.

In Delhi, the ruler Muhammad bin Tughlaq, presented him with precious gifts and a well-appointed house to stay in. He was given the prestigious job of a Qazi in the royal court. Battuta and the ruler had an uneasy relationship and though he stayed in India for seven years in all, he had soon become restless and was anxious to leave.

Battuta also visited the Sindh and Punjab areas of what is now Pakistan. He praised the bazaars and well-built towns and was fascinated by their ancient cultures, and hospitable people. He visited the city of Uch, known in Pakistan as Uch Sharif, which lies on the banks of the river Indus. Uch is said to have been founded by Alexander the Great. Battuta then travelled to the ancient city of Multan where he spent two months.

Battuta describes the pearl divers in the Persian Gulf who it is claimed could hold their breath for long periods underwater even up to one hour. We even read of the exotic and esoteric practices of the mystics living in areas that are now part of Iraq who walked on hot coal and put burning-embers in their mouths. They did this in a state of ecstasy and in a spiritual trance.

Ibn Battuta had fearful adventures almost drowning in shipwrecks and once when he was travelling on a small, rickety, and suspect boat along the coast of the Persian Gulf he sensed rebellion against him in the air among the sailors. Discretion is always the better part of valor and Ibn Battuta asked to be set on land. He requested one of the crew to accompany him as a guide because the location looked deserted, bleak, and inhospitable. Unfortunately, the companion had murder on his mind and attempted to drown Ibn Battuta and when he failed, misguided him in the desert. Ibn Battuta barely survived with his entire body black and blue with physical trauma. His feet, in particular, were severely burnt and bruised.

Ibn Battuta enthusiastically writes of Damascus as the most wondrous city in the world. He described Baghdad, Cairo, and Mecca as great cities with generous, cultured and hospitable people. He describes a scent used by people as part of Islamic culture. He notes that Baghdad still showed evidence of the Mongol invasions of the previous century. In China he was shown hospitality by Muslim merchants and by the time he arrived in Beijing the Chinese emperor was dead. Ibn Battuta waited around but seeing no point turned about and headed for India but then decided not to go to Delhi to report to the king. Instead, he headed for his homeland in Africa. On the way he made one last detour to Sardinia, then in 1349, he returned to Tangier by way of Fez.

The famous Islamic saying or hadith, attributed to the Prophet of Islam (PBUH), about seeking knowledge even if it meant traveling to distant China, would have also been a spur to the young Ibn Battuta. Now when this saying was first quoted in the seventh century, China seemed as far away as the planet Mars. So, China was a metaphor for a distant and faraway place, in this case at the other end of the known world. Travel to China meant long periods on the road facing various dangers and challenges in uncertain lands with different customs. China would have been a remote and isolated land of mystery.

The idea of knowledge as something highly desirable, almost a sacred duty, was widely known in the Muslim world. Quranic verses and hadith emphasised the importance of learning and the acquiring of knowledge, both for men and women. The Arabic word for knowledge is ilm and it is the second most used word in the Quran after the name for God and it is addressed to men and women. A hadith which sums up the Islamic philosophy towards learning, and is one of my favourites, is: “The ink of the scholar is more sacred than the blood of the martyr.”

It is clear that this simple philosophy, the pursuit of knowledge through travel and discourses with learned scholars, was a factor driving Ibn Battuta.

We learn that at the time of Ibn Battuta the main library of the 93 libraries in Muslim-ruled Cordoba, then one of the great cities of Europe, had some 600,000 books. In contrast one of the biggest libraries in Christian Europe had 600. Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid empire was famous for its libraries, colleges, and scholars. In 1258 when the Mongols devastated Baghdad, they set out to destroy the books that contained the wisdom of Islam. It is said that the rivers turned black as the Mongols set about destroying the libraries and throwing books into the water. It is one of the great ironies of history that the same Mongols soon converted to Islam and that some of Ibn Battuta’s benefactors were some of these converts.

The problem with travel writing, especially years after events in distant lands covering decades, is that dates, places, and names are often forgotten or mixed up. It is well to remind ourselves that in his day Ibn Battuta did not have a computer, typewriter or dictaphone which would be invented centuries later. He was even accused of inventing stories just as Marco Polo was. This is the syndrome often faced by fishermen who describe the size of the fish that got away to sceptical friends. The common phrase for these stories is that they are little more than tall tales.

Lessons from Ibn Battuta for Today

Reading about writers from the past and historical figures invariably raises the question: what, if any, relevance do they have for us today?

Ibn Battuta's observations and writing provide an important pedagogical purpose. They allow us to glimpse from the distance of our times something of the Golden Age of Islam, although it was the tail end of that phase of history. It was a time of invention and scholarship, also a time of great interfaith interaction. To start with we note that there is a Muslim civilisation with a distinct unity of culture and customs stretching from Spain to China, Damascus to Mali and Tangiers to Timbuktu. Within different local traditions there is a recognisable Islamic adab or culture where Arabic is widely spoken as a common lingua franca. We note the wide-spread respect for learning, the inclusivity of approach in dealing with those of different faiths, and the culture of hospitality.

By the time of Ibn Battuta the great Seljuk administrator Nizam-ul-Mulk had established his colleges or madrasahs as centres of excellence across the Muslim world, Sultan Salahuddin, who was a patron of these colleges, had retaken Jerusalem, the ferocity and might of the Crusades had faded and the Mongols who set out to destroy Islam, and indeed did so with Baghdad, had converted to Islam. From one end to the other of the Muslim world the verses of the spiritual and literary giants like Rumi, Ibn Arabi and Hafiz, the Shakespeare of the Persian language, were recited and appreciated. New Muslim empires, the super- powers of their age, were on the horizon–the Ottomans, the Safavid, and the Mughals. It is very much a Muslim coloured world, and we get a close look at it: the men and women are thirsty for knowledge, the bazaars are joyous and colourful and trade in silks and satins and sell exotic foods and spices. We sense the exuberance of the travellers Ibn Battuta meets along the way and the stories they tell him.

We are also aware that in the future these societies would be irretrievably compromised and then altered drastically as western powers arrived inexorably with their cannon and warships to colonise the Muslim world, now one society, now another. So, in essence in Ibn Battuta’s book we have one of the last and most authentic global views of the Muslim world in one phase of its history, all the more remarkable as it also provides fine-grained details of society at the micro level.

Perhaps the most important lesson on reading Ibn Battuta is for the young. The lesson is to explore the world around them and appreciate and understand different cultures and societies, to allow yourself to dream, to endeavour, to achieve the ideal. Remember Ibn Battuta starts with nothing more than his faithful donkey as he sets off on his journey and he finds everlasting fame. Here we are still talking about him over half a millennium later.

We are also reminded of the importance of ilm or knowledge. We see its effects on society where scholars are respected. Ibn Batuta had begun his journey with the intention of meeting scholars along the way; and he does. We learn of friendly hosts treating the stranger or traveler kindly and with hospitality. This hospitality is at the heart of all faiths, especially the Abrahamic ones. I recall Lord Jonathan Sacks, the former Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom, emphasising God’s message to Moses to be kind to strangers and reminding him that the Jews were once strangers. Lord Sacks explained that Abraham kept one side of the tent open in case a stranger called seeking assistance at night.

We are also made aware of inter-faith understanding and cooperation throughout Ibn Battuta’s journey. This is a desperately needed lesson for our world today where so many religions appear to be locked in senseless and violent confrontation. Ibn Batuta describes his visits to shrines and holy men of all the faiths. He travels to Sylhet to meet a renowned Muslim spiritual leader. He finds an impressive man, fair and tall. In Quanzhou in China, he climbs up a mountain to meet a celebrated Tao monk living as a hermit in his mountain cave. He describes Christians, Jews, and Muslims living side-by-side in the prosperous towns and cities along the Anatolian coastline. He especially praises the local Christians there as pleasant and hospitable. He also comments on their handsome looks. He notes the use of marijuana.

In some places he observes with a certain touch of exasperation the manner of dress of the women which he finds too revealing, especially as they had converted to Islam and were required to dress more modestly. He does not spare the men either. In Cairo, on first arriving, he attends the baths where he discovers men in a state of complete nudity which was against the rules of the bath house. He promptly reports the matter to the authorities.

He travelled to what is described as Black Africa twice and noted the magnificence of the grand court of the legendary African ruler Mansa Musa and the wealthy multi-cultural trading centres on the east coast like Mombasa and Kilwa. He was appreciative of the welcome he received, especially in Mogadishu. He noted a "hostility toward the white man."

Ibn Battuta describes the devastation caused by the widespread plague or the Black Death and the many lives lost in Damascus, over 2,000 a day in that city, and the terrible scenes of death as he travels down via Gaza to Cairo which lost over a thousand lives daily. On the way he sees the devastation of Gaza, an area depopulated. He describes how Jewish, Muslim and Christian religious leaders united to lead processions with their holy books imploring God’s intercession.

Some of the greatest Christian Jewish, and Muslim scholars lived at the time and many of them interacted with each other intellectually and theologically. St. Thomas Aquinas, one of the most celebrated Christian spiritual leaders quoted the notable Muslim scholar Averroes over 500 times in his classic book Summa Theologica. The legendary Jewish Rabbi Maimonides wrote in Arabic and after escaping Cordoba in Andalusia finally ended up in Cairo as the medical advisor to Sultan Salahuddin himself.

Ibn Battuta is a philosopher contemplating the variety of human societies across the Muslim world, an anthropologist studying culture and customs, a travel writer recording the different political situations he encounters and a religious scholar reminding people of the mores and duties of Islamic behaviour. Although he writes his masterly work after returning home it is written as if he is still in the saddle and on the move.

Battuta’s observations rely heavily on the anthropological method of participant observation. He literally participated in the societies he wrote about, often marrying into the community. But he is more than a dry as dust scholarly writer. He is also a sharp observer who captures the richness and complexity of the societies he encounters. His description of the foods and fruits across the Muslim world would delight a gourmet.

Reading Ibn Battuta's comments on passing through Gaza as he crisscrossed what we now know as the Middle East and the cordial relationships that existed between Jews, Muslims and Christians in the context of the current state of desperate disrepair, one cannot help but feel that something profound has been lost. Perhaps the gloom may be alleviated by the optimism of Ibn Battuta and his innate belief in the goodness of human nature.